One might argue that the demolition of the Century Building commenced in 1993, when real estate speculator Mark Finney bought the edifice and proceeded to, in essence, strip it for parts. But the process began in earnest last Wednesday, October 20, when Environmental Operations Inc. swung its wrecking ball.

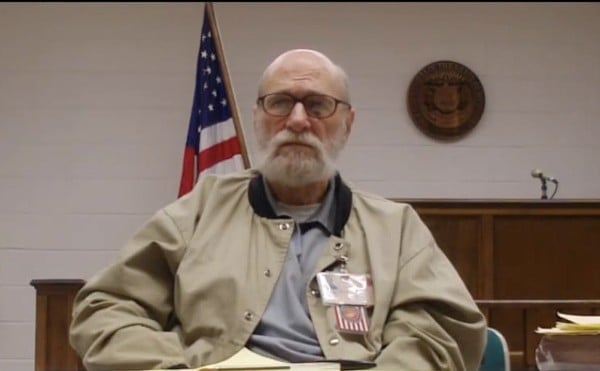

A day earlier, Larry Giles was there.

The 57-year-old Giles and two helpers are perched on a scaffold, taking a crowbar to the Century's Locust Street entrance, a glorious but tattered cast-iron doorway. The president of the nonprofit St. Louis Building Arts Foundation, Giles secured salvage rights to the Century from the city for free and is now carting away whatever he can. Giles, who has been recovering architectural remnants since 1972 and knows as much about St. Louis architecture's decorative past as anyone, possesses one of the largest collections of architectural artifacts in the nation, ranging from cast-iron storefronts to terra cotta entranceways to ornamental bricks. (He was in the Century a decade ago when Finney arrived on the scene, and he managed to sock away parts of the theater that was once housed in the building.)

Eventually Giles and Steve Trampe, a St. Louis developer best known for his renovation of the Continental Building, intend to display the artifacts in a national architectural museum to be built on six acres on the east side of the Mississippi River. They're in the process of raising capital, Giles says, and the city of East St. Louis has dedicated land for the project, dubbed the St. Louis Architectural Museum.

Still, if he had it his way, the Century would still be standing. "It's a real tragedy," says Giles, taking a break from the grunt work. "It's a significant building in a lot of ways -- aesthetically, structurally, historically. There's more history crammed into that building than most people know."

Once he's finished extracting the Locust Street doorway, Giles aims to pry off the extensive exterior cast-iron detail work that separates the first two floors. Then he'll tackle the massive stone archway that comprises the Century's grand entrance on Ninth Street and some riveted steel framework from the internal skeleton.

Back when the Century was built, Post Office Square was the most prominent block in a bustling downtown, Giles explains, so the building was designed to handle a lot of traffic. "It was a very desirable location," he says. Then, after a brief pause: "And I guess it still is today."