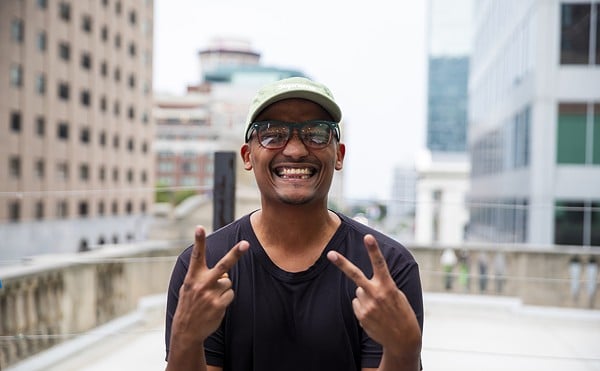

When Steve Marzette arrives at a Maplewood bus station on a cold weekday October morning, he has already been in transit for more than an hour.

First, the 95 MetroBus from Penrose Park to the Central West End. Leaves at 6:58 a.m. Then the westbound MetroLink from the Central West End to Maplewood. Leaves at 7:26.

He's going to catch the bus from Maplewood to Ellisville at 8:05. By the time he arrives at his job at the Pasta House there, Marzette will have been on the road for two hours. On the way home, he catches his first bus at 3:26 p.m., and gets to his doorstep at 5:30.

Six days each week, Marzette, 59, spends four hours on public transportation.

It gets to him, he admits. But, he says, "I can't do nothing about it. Ain't got no car."

He makes $9 an hour as a dishwasher.

Once he gets home, Marzette says, "I relax, look at the TV, be with my lady. Don't come outside until the next morning. I live in a pretty rough neighborhood."

He chuckles. Penrose Park is located in a part of north St. Louis that has a high rate of violent crime. In May, two children were among four people wounded in a shooting just blocks from Marzette's home.

"Bullets go flying. It's something else. Everybody got a gun now," another passenger volunteers.

When the bus leaves from Maplewood, each seat is filled. The majority of passengers, including Marzette, are black and 90 percent of them work in fast food, Marzette posits. You can tell by the black pants.

They are part of a workforce that travels from the city to restaurant jobs in west St. Louis County — a workforce that is too small to keep the restaurants adequately staffed. Some restaurants have closed or shortened their hours. Owners and managers have met to try and come up with solutions.

In the meantime, they rely on people like Marzette. And he relies on his job for the paycheck. Nevermind that it requires a four-hour commute for what economists say is not a livable wage. It's a strained arrangement that's not ideal for either side.

In July, the owners of the Greek Kitchen, a popular Ellisville restaurant, posted on Facebook that they were closing the business.

"We have worked very hard to make our restaurant a cozy and inviting place for all to enjoy but for the last year we have had a very difficult time getting staff to help in the kitchen," wrote co-owner Joe Kandel. "As recent as the last couple of months Lisa and I have been very short staffed having to be on grill, make the food, and trying to take care of the day to day business."

People left 169 comments and shared the post 41 times. "The food, hospitality, and service are terrific," one wrote, "but the best part has always been how much your food makes me feel like I was at my Nana's table!!!!"

Ellisville is a suburb about a 30-minute drive west of St. Louis. Its median household income of $74,074, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, compares to $40,346 in the city. Ellisville Mayor Adam Paul has been a vocal opponent of a proposed merger between the city and county. He told St. Louis Public Radio that residents of Ellisville don't want "a socialism-type government on the local government." The non-binding measure Paul put on the April municipal ballot to oppose such a merger drew 81 percent support. The city also hired a lobbyist in Jefferson City to oppose such a merger.

Like it or not, though, Ellisville is dependent on the broader metro region for at least one critical thing: hourly workers. After closing, Greek Kitchen co-owner Lisa Nicholas told St. Louis Magazine, "I think the reasons why we — and many businesses in Chesterfield, Wildwood and this west-county area — can't get restaurant help is that a lot of restaurant workers come from the city and farther east. They are taking buses or driving 45 minutes to work, and it's just not worth it for them. There are lot of kids out here, but they just don't want to work in a restaurant."

Enough restaurant owners in the area acknowledged having the same problem that the West St. Louis County Chamber of Commerce decided to hold a forum to discuss the shortage. More than twenty people in the restaurant industry attend the meeting, held in late August at the St. Louis County library branch in Ellisville. Many of them point to lack of public transportation as a primary reason for the shortage.

A recent Apartment List study relying on U.S. Census data found that more than 24,000 St. Louis-area residents travel more than 90 minutes to get to work daily — an 89 percent increase from a decade ago. Those commuters are far more likely to be users of public transit. While 95.8 percent of commuters drive to work in the St. Louis area, only 68 percent of so-called "super commuters" do so. In many cases, these appear to be residents of the city, and of less affluent suburbs, relying on buses to get them to jobs in west county.

"We have a guy who works at Circa STL who it takes two and a half hours, one way," Tim Walsh tells people at the chamber of commerce forum. Walsh is managing officer of the Des Peres restaurant, which focuses on classic St. Louis dishes. "When he's working nights and I'm there doing whatever, I offer to take him home ... It's out of the way but it saves him two and a half hours of riding the bus, and hopefully it gets to where he realizes we're trying to do something to help him stay at the restaurant."

Lori Kelling, president of the chamber, relays that the owner of Walnut Grill in Ellisville told her he has an employee whose car went kaput and who now spends six hours on the bus each day.

The other source of labor for the restaurants, many say at the forum, is local teenagers. One person suggests a job fair at the schools. Another person says schools should give out awards to students for their paid work rather than just for grades or involvement with clubs or sports.

But Walsh says Parkway South High School already asked him to participate in a job fair for students. The restaurant made toasted ravioli and gooey butter cake, he says, "in the hope that some of the kids at the school would say, 'Hey, we want to come there and work for you."

"Not one person came to the restaurant," he says.

The meeting to find solutions quickly devolves into a conversation about how things aren't the way they used to be.

"The kids today, there is no need to have a job because mom and dad take care of them," says Walsh. He turns to a representative from the Philly Pretzel Factory in Ballwin. "You mentioned how some kid pulls up in a Maserati to work at your restaurant —"

"To get pretzels," the rep clarifies.

"To get pretzels," Walsh says. "They don't need a job."