One day in 1906, a dead man stepped off a steamboat in Cuba.

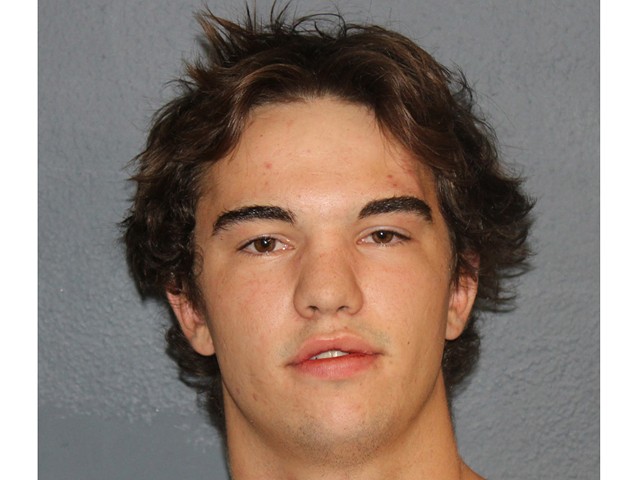

Félix de la Caridad Carvajal y Soto, known as "Andarín," or "the walker," disembarked the boat alone. His short, scrawny frame reached just an inch or two above 5 feet. A wispy mustache extended well off his face. He easily passed through a customs house and had no luggage, despite a weeks-long journey across the Atlantic Ocean.

Traveling light wasn't unusual for Carvajal. Neither was his ability to surprise people.

The 31-year-old had become something of a celebrity for his exploits during the 1904 men's Olympic marathon in St. Louis. He'd arrived for the race starved and wearing heavy boots. He even took a nap during the middle of the race, yet he still beat renowned runners. His clear talent for distance running took him to Athens in 1906, where he was expected to win the Intercalated Games' marathon.

Only he never showed up. "He had disappeared like a ship lost in a storm at sea, leaving no trace," one newspaper reported. By the time Carvajal arrived back in his native Cuba that day in 1906, the country had already mourned its first Olympian. No one, presumably even his family, had heard from him in months. Newspapers published his obituary. A Canadian, Billy Sherring, won the Athens race with a time of 2 hours, 51 minutes and 24 seconds.

No one knew whether Carvajal even made it to Athens. Most believed Carvajal lingered where his boat stopped in Italy. And there, like a fool, Carvajal displayed his Cuban gold in some Neapolitan dive and "drifted out on the tide that night with his throat cut," the Buffalo Commercial reported. Others wondered if he lost his money gambling, which he had reportedly done in the past.

The truth of his disappearance was far less dramatic. Carvajal just had the date of the marathon wrong.

Carvajal's tumultuous life story is often unbelievable. For a poor man from what was then considered a remote Caribbean outpost southwest of Havana, he racked up an impressive array of accomplishments with not much more than pure skill and blind confidence. Originally a postman, Carvajal would become one of Cuba's most famous athletes.

It's difficult to pinpoint where the story of Carvajal's life of exploits begins. It may have started when he was a young boy in Havana, where he raced his friends — and horses — in the hills of the country. Or it may have begun during the Spanish-American War, when Carvajal served as a courier for General Máximo Gómez Báez and at one point ran across Cuba in 16 days to deliver a dispatch. There was also the time when, at 14, he won his first race by outlasting Mariano Bielza, a Spanish athlete known for distance running. They started the race at 8 a.m., and Carvajal did not stop until 7 p.m. — two hours after Bielza gave up.

But Carvajal most certainly achieved legend status in St. Louis at the 1904 Olympic marathon. The race, part of the first-ever Olympics to be held on U.S. soil, is now recognized as one of the most bizarre athletic events in modern history. Men came near death, were chased off the course by a pack of wild dogs, endured oppressive heat and overcame a dubious science experiment meant to test their athletic performance.

Yet Carvajal, as he did for most of his life, chugged on. And years later, when he arrived in Cuba after failing to compete in Athens, Carvajal did what he had always done. He took off running.

In 1904, James Sullivan was on a mission. Sports, at the time, were seen as a way to advance the United States, and Sullivan, the head of the Olympics in St. Louis that year, believed American athletes were the fittest.

The 1904 Olympics in St. Louis were a mere appendage to the World's Fair. Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the International Olympic Committee (still the authority responsible for the games today), refused to attend. He predicted the games would be nothing more than a sideshow, and according to his memoirs, he detested Sullivan. He wrote Sullivan was often "carried away by enthusiasm."

The men's Olympic marathon in 1904 serves as an excellent example of Sullivan's hubris. Thirty-two men left the starting line around 3 p.m, but an unsuitable course covered in dust, a science experiment carried out by Sullivan and brutal heat allowed only 14 to finish.

Newspaper clippings from 1904 and books written on the fair since paint Sullivan as a powerful, ambitious and arrogant man who was the nation's "acknowledged authority on athletics and the preferred referee at nearly all important athletic events in the country," writes Nancy J. Parezo in The 1904 Anthropology Days and Olympic Games. He hoped the fair would serve as a source of scientific knowledge, a platform on which Sullivan would administer experiments to advance sports science.

Sullivan, who organized the fair's sports program as director of its Physical Culture Department, thought Caucasians were the superior race, both mentally and physically, and was the creator of the fair's Special Olympics, in which "natives" — most recruited from the so-called living villages where fairgoers could marvel at other cultures — would compete in various events. The selection of sports included archery, a greased pole climb, tug-of-war and, for women, a tipi-raising contest in which participants had to erect a version of a teepee. Very few native demonstrators earned a wage at the fair, and the Special Olympics were one of the only ways to earn money.

Carvajal likely had no knowledge of Sullivan, nor the dubious events he would hold under the guise of scientific knowledge. Carvajal only wanted to run.

Carvajal raced whoever or whatever he could find as he grew up. In 1900, he ran 2,023 miles within Cuba, and completed the tour in 54 days. He got lost in a forest for two days during the run, and it was reported he survived on nothing more than wild fruit. This earned him widespread attention in Cuba.

He "always loved to run," Carvajal told the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1905. Before he came to America for the Olympics, he had a vision of himself receiving a crown of laurel from the hands of the Olympic Games Committee at the St. Louis World's Fair.

But Carvajal was desperately poor. Traveling to St. Louis without the support of his government would have been impossible.

There's never been an English-language biography of Carvajal, so what we know about his life today is almost entirely gleaned from contemporaneous news accounts, which are colorful in their details and not always rigorously sourced. The Evening World wrote that a couple of months before the race, Carvajal, a "ragged, dirty, vagabondish sort of scrawny fellow" elbowed past the mayor's secretary and asked the mayor for money in the "slang of Cuba." The mayor, while puffing a cigarette in his armchair, laughed and declined.

So Carvajal decided to do what he did best. He started running. He ran loops around Havana's city hall plaza. One report said he ran all day and stopped after the mayor left to go home in the evening, only to find a crowd watching Carvajal run and run. Another said Carvajal ran loops around city hall itself, passing the mayor's window over and over again. Toward the middle of the day, the story went, the mayor caved.

Either way, Carvajal got his money, and he was on his way to run his first official race.

But Carvajal's plans rarely went smoothly. He lost all his money in a craps game after his steamer arrived in New Orleans, and he had to run to St. Louis.

According to a 1950s TV special on Carvajal, he ran and walked from New Orleans to St. Louis. He begged for food or stole it from orchards and farms. He slept on haystacks in barns. He occasionally accepted rides, but for the most part, he ran.

Many of Carvajal's competitors in St. Louis were darlings of the burgeoning running scene. Some of the most formidable contenders included John C. Lordan, who won the Boston Marathon in 1903 with a time of 2 hours, 41 minutes and 29 seconds; W. R. Garcia of San Francisco, who was known for dominating 10-mile runs; and Thomas Hicks, who placed second in the Boston Marathon that spring.

Some of them would come near death in St. Louis.

Carvajal arrived in St. Louis the same day as the marathon. According to some reports, he came to the start line with an empty stomach after not eating for two days. He wore the same clothes he traveled in — Army surplus pants, which were part of the official uniform of Havana mail carriers, a long-sleeve shirt, stockings that reached to his knees, a beret and a pair of brogans, or street shoes, which each weighed about two pounds, according to the Boston Globe.

Another Olympian took pity on Carvajal and found a pair of scissors to cut his pants into shorts, though reportedly Carvajal at first refused, as his trousers were the only pants he had.

But it was an extremely hot day on August 30, 1904, at the tail end of a St. Louis summer. Runners described a stifling, sticky humidity as temperatures soared to around 90 degrees. Yet Sullivan, who wanted to test the effects of dehydration on athletic performance, provided only one water station throughout the entire 24.85-mile course. It was a well at the 12-mile mark.

Louisiana Purchase Expedition President David Francis fired the starting gun around 3 p.m., and the marathoners took off to the cheers of about 10,000 spectators piled into what's now Francis Stadium on Washington University's campus. The stadium contained a cinder track in 1904. Runners looped around the one-third-mile track five times before embarking on a rocky course of unpaved roads that stretched through the "country," or modern-day west St. Louis County.

The course was insufferable. Numerous steep hills throughout the 25 miles would later cause critics to describe it as one of the worst-planned courses for a marathon ever.

From the Boston Evening Transcript: "The course, after leaving the stadium, led over hills and through vales innumerable, being pronounced one of the most up-hill courses ever traveled by athletes in events, and the roads were deep in dust. Many of the men were overcome by the heat, but were brought back to the stadium or carried along the route."

The dust seemed like the most difficult part. A few days prior, race officials drove the course when the roads were muddy from summer storms, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. After days of heat, the mud was gone, and at one part of the course, at Manchester Road, the street was "inches deep in dust, and every time an auto passed, it raised enough dust to obscure the vision of the runners and choke them."

A dozen men on horses cleared the course of spectators before the race began. The cloud of dust this caused was worsened by a fleet of cars carrying race officials, physicians, trainers and scientists. Runners also had to weave through traffic, delivery wagons, trolly cars and people walking their dogs. Two men in an automobile were seriously injured when, distracted by the race, their car plunged down the side of a 30-foot embankment.

The noxious fumes from all the vehicles almost caused one man to asphyxiate. Garcia, the medium-distance runner from San Francisco, was found near death on the ground by a local couple who took him to a hospital, where he received lifesaving emergency surgery. He had ingested so much dust, according to reports, that it had ripped the lining of his stomach.

Carvajal started toward the back of the pack. From all accounts, he seemed to eat up the attention he received as the marathon went on. He often stopped to chat with spectators, or tip his hat at them (he ran the whole race with the beret he'd arrived in). One report said he stopped next to an automobile where a party of people eating peaches refused to give Carvajal one, so he stole it and ran, gobbling the peach as he traveled down the road.

Yet Carvajal's hunger eventually became too hard to ignore. At the halfway point, one reporter described Carvajal's running as a "flat-footed" clatter kept at a speed that "seemed ominous to American laurels." Carvajal eventually decided to go slightly off course to a nearby orchard for some fruit. He ate either a rotten or unripe peach or apple. Whatever it was, it gave Carvajal stomach cramps. So he stopped for a nap under a tree.

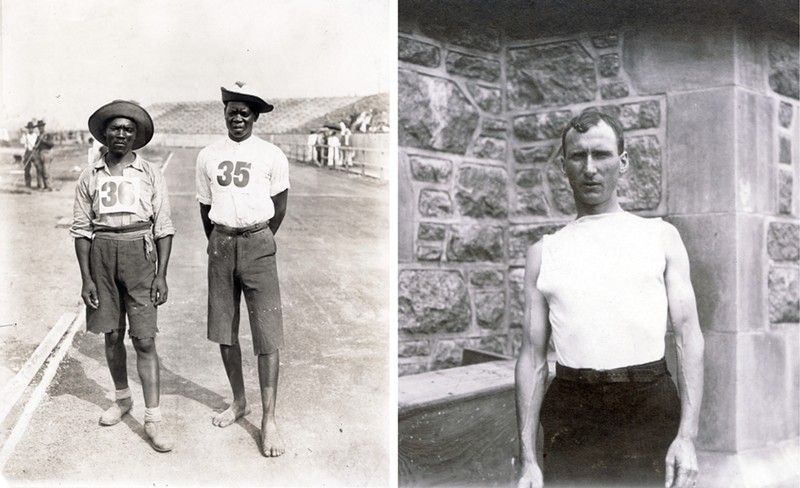

Meanwhile, the race chugged on. Among the "natives" Sullivan coerced into joining the race were two Zulu men from the South African Boer War Spectacular concession. Len Taunyane and Jan Mashiani, referred to as "Lentauw" and "Yamasani" by the press, were mail carriers. They did well, with Taunyane taking ninth despite running barefoot. Mashiani placed 12th and likely would have done better had it not been for the two dogs that ran him off course.

Toward the front, Thomas Hicks, an Englishman representing a Cambridge, Massachusetts, YMCA, was running a good race. He was in the front of the pack for the first 15 miles. But when he grew tired, his trainer, Hugh McGrath, gave him just the thing to help: a dose of strychnine sulfate, better known as rat poison, which was thought to enhance athletic performance. He gave Hicks one dose and another three miles later — this time with two egg whites and a sip of brandy to chase it down.

Unfortunately for Hicks, McGrath was of the same mind as Sullivan. McGrath thought water destroyed athletic performance. So Hicks was never allowed to drink water, though his trainers did sponge his body with water warmed by the boiler of a steam automobile.

One of Hicks' handlers, Charles Lucas, would later describe Hicks' condition in the final stages of the race: "His eyes were dull, lusterless; the ashen color of his skin and face had deepened; his arms appeared as weights well tied down; he could scarcely lift his legs."

Toward the end, Hicks suffered from what Lucas described as "hallucination." He seemed to think he was nowhere near the finish, that he still had 20 miles left. "His mind continually roved toward something to eat," Lucas wrote. "And in the last mile, Hicks continually harped on the subject."

Weak, and so exhausted that two men had to hold him upright, Hicks crossed the finish line in second place. He'd lost eight pounds during the race. It was reported he walked around the stadium in a stupor and had to get rushed out before receiving his trophy.

He survived, and Sullivan brilliantly deduced that strychnine sulfate did not enhance athletic performance. In Marathon Running, a training book Sullivan wrote years later, he did not recommend avoiding water. The International Olympic Committee didn't ban strychnine until the 1960s.

Hicks "went lame and had to retire" from athletics, the Boston Evening Transcript reported in 1905. Hicks did compete in a handful of races in the next few years, however.

He later became a professional clown.

Reporters didn't pay much attention to Carvajal until nearly the end of the race. He had been off-course for so long during his nap that race dispatchers who telephoned runners' places for stadium announcers ran ahead of him.

But now, awake and refreshed, Carvajal resumed running with vigor. He closed the gap to his competitors, ultimately finishing fourth at an unrecorded time. According to a 1906 Evening World profile on Carvajal, he sped up when he at last entered the stadium for the final meters of the race. His street shoes loudly clopped against the cinder track. His face showed strain. Spectators started looking over their programs as they wondered who the Cuban was.

Blind with dust and sweat, Carvajal didn't stop when he passed the finish line. He ran another lap around the track, and people nearby had to stop him.

Carvajal wept after he learned his place. He wanted to come in first. Many athletic experts, according to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, said he could have won if he had trained or had any support during the race. He also had the ideal marathoner's physique. At little over 5 feet and between 115 to 130 pounds, he didn't have much to carry.

"He was a wonderfully tough little piece of machinery," the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported in 1907.

Carvajal finished the "freshest." He didn't rest or look for any food after the race like the other runners. In fact, he stayed to walk around the fair. "He must be a freak," the headline of one newspaper read. Carvajal was seen late that night on the Pike, a stretch of the fair on what's now Lindell Boulevard that contained 50 different carnival amusements including contortionists and circus animals.

Few outlets quoted Carvajal, and those that did wrote his words in the way reporters must have understood him. On the night of the race, Carvajal reportedly told the Globe-Democrat: "Champeen, he go to bed; me stay out Fair; walk around six, seven hours; me no tired."

Though he was the second runner to cross the finish line, Hicks was eventually named champion with a time of 3 hours, 28 minutes and 53 seconds. It was a glacial pace compared to today's standards. Now, the world's best marathoners finish with times around two hours.

The 1904 marathon's first winner, Fred Lorz, stopped running after nine miles and hitched a ride in a stadium car.

He re-entered the race around the 19th mile and took a picture with Alice Roosevelt, the then-U.S. president's daughter, but angry officials later learned he cheated. Lorz admitted to it and tried to pass off his lie as a joke. He was temporarily banned from athletic events, but he entered the Boston Marathon a year later. He won, this time without cheating — under watchful eyes.

Night had fallen by the time all the marathon runners straggled across the finish line. The glare of the fair's weekly fireworks cast a glow over the stadium.

Carvajal stayed in St. Louis for the next two years, likely because he had no means to leave. He worked odd jobs, once at a peanut concession in a building that hosted jai alai, a Latin sport similar to racquetball.

The Missouri Athletic Club took him on, and he ran marathons for the club, often placing well.

The club's then-Vice President Isacc Hedges hooked Carvajal up with a job operating elevators at the Cupples Building downtown. But he wasn't very good at it. Carvajal terrified his passengers when he continuously "shook" them into "cataleptic fits."

Messenger boys had a "mortal fear" of the 3-foot-long machete Carvajal carried at all times. When his "passions rose," he'd chase them out of the building while brandishing his knife and screaming curses in Spanish. Messengers and nearby businessmen begged Hedges for Carvajal to be "caged, or at least muzzled and handcuffed."

"Needless to say, he was given a wide berth from that time on," the Globe-Democrat wrote.

Carvajal eventually quit his job, But outside work, he kept running. He spent much of his time at the athletic club's gymnasium, where he ran 4 to 10 miles each day.

"Almost any day a person may go into the club and see Felix plugging around the track," the Globe-Democrat wrote. "Two hours later a return visit will still show Felix still going round and round, sometimes sprinting and at other times barely moving at a dog trot, but never walking."

Yet St. Louis was never his true home. The first snow he endured in the city made him long for the warmer weather of Cuba. He had saved some money and planned to go to Havana or Key West, possibly even Colorado, eventually doing so around 1905.

In March of that year, local newspapers reported that he'd been living "hand-to-mouth" since his arrival in St. Louis and that he struggled to find work he could do.

On March 10, 1905, he told a reporter he was leaving for Tampa, Florida, where his father was the proprietor of a cigar store. He planned to run the entire distance.

"Fine train this," Carvajal told the Globe-Democrat while patting his thigh. "No tire, either. Maybe it will take me three months. I don't care. Tired of this fellow and that fellow who say here: 'Felix, 10 cents, quarter.' Me no beggar. I say, good-by St. Louis next week, sure."

His travel plans reportedly screwed over the Missouri Athletic Club, as he was slated to represent the club in an upcoming marathon. He said he was sorry he couldn't make the race, but he still asked the club to furnish him with new shoes for his journey.

"I'll eat fruit on the way," he said. "And run sometimes 15, 30 miles a day. Sometimes walk."

It's not clear whether Carvajal ever made it to Florida. One 1906 profile reported that Carvajal was arrested in New York, where he jogged alongside cable cars before being admitted to a mental hospital as an insanity patient. For three days, he was held in a cell, where the hospital gave him three cold baths to "find out his pedigree," presumably to figure out who his family was. A huge language barrier prevented this.

"He couldn't talk English, or French, or even Spanish," the Evening World reported. "His speech was a jargon made up of Cuban slang, and when they questioned him he howled. When he howled he got another bath."

A few of Carvajal's friends eventually turned up. Authorities asked, "How long has he been crazy?"

"He isn't crazy!" his friends replied. "He's a runner!"

Carvajal was let go, and he returned to Cuba on the next available boat.

What happened in Carvajal's life after he left the U.S. went largely unrecorded, at least in American papers. None made any mention of Carvajal's family, except for one that said he had a wife and several children in the city of Santiago de Cuba. In 1928, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote Carvajal planned to run from San Francisco to New York while pushing a handcart, but later offered no follow-ups.

Almost exactly 119 years after the 1904 men's marathon, a stifling heat blankets St. Louis. The humidity feels tangible, like steam from a shower. The possibility of running a marathon in such temperatures feels unthinkable.

In University City, a vine of green ivy drapes over a wooden historical marker for the 1904 marathon's route along North and South Road. Employees at the Maine Stain car detailing shop across the street are clearing their parking lot with a hose. A firefighter at the station next to the marker chats on the phone outside. In this day's 100-degree heat, the nearby River Des Peres is as inert as the hot, stagnant air.

At the marker, the runners in the 1904 marathon would have been in the home stretch of their race. The scenery would have been much different. University City was mostly small farms and dirt roads. Nearby, Edward Gardner Lewis had recently broken ground on his Woman's Magazine headquarters. Its octagonal tower currently houses University City's city hall.

Today, the story of the 1904 men's marathon is one of the most lionized stories to come out of the 1904 World's Fair and Olympics, according to historian Amanda Clark.

"People seem obsessed with it," Clark says. "They focus on the wackiness of it." It has almost the same draw as the axle of the fair's Ferris wheel, which according to local lore, is buried somewhere underneath Forest Park.

The axle isn't buried under the park, says Clark, who is a tours manager for the Missouri Historical Society. But people are still "obsessed with the damn wheel."

"For some reason, people really want that piece of metal to be hiding in the park," Clark says.

It's important to note: Nearly every account of Carvajal's life varies in the details. Did he stuff himself with peaches or apples before his nap during the Olympic marathon? Did he cut off his trousers himself, or did another runner do it for him? Did Havana's mayor award Carvajal money after he circled city hall for a whole day, or just a few hours? There are also stories that claimed Carvajal ran in Cuba to raise money, and other stories that say he refused money.

One thing is sure: Carvajal made a lot out of a little. He was never a rich man. Far from it. He was born poor and died poor. According to EcuRed, Cuba's government-funded online encyclopedia, Carvajal lived the last 20 years of his life in a "miserable shack" under the Puente de la Lisa, a bridge in Havana. Whatever money or winnings Carvajal garnered in his life he used so he could run more, often traveling farther than anyone, even more than those far more well off could have dreamed at the time.

And whatever he had was enough to make him into a legend. His story and that of the 1904 marathon seem so crazy, so sensational, that stories of other events or people at the 1904 World's Fair often fade into the background.

What happened at the fair more than 100 years ago may seem crazy or barbaric to us now, but hindsight isn't always perfect. That's the thing about history — it's only a matter of time before the lives we're leading now seem just as outlandish.

"We've always been awful, and we've always been wonderful; we always think we know what we're doing, and we never do," Clark says. "History gives a continuity I find comfort in, especially right now. The world feels absolutely insane. But if you start digging through history, the world has always felt insane."

Subscribe to Riverfront Times newsletters. Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed