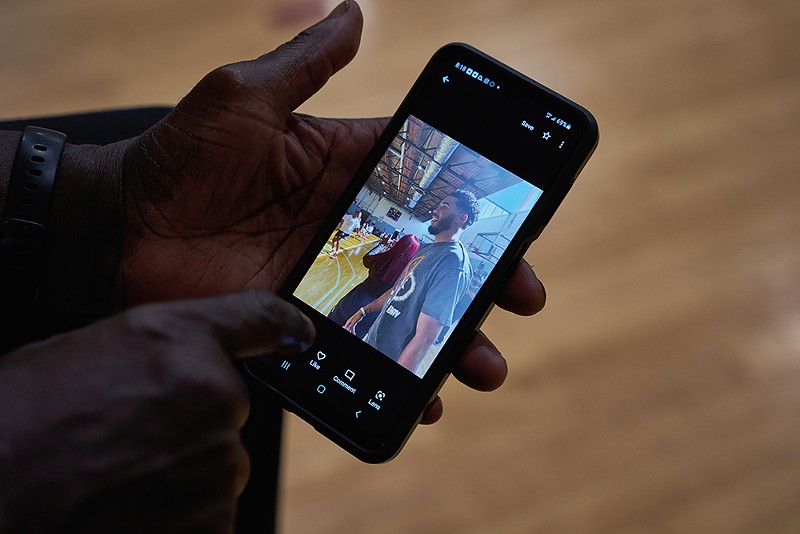

It feels like a normal day at the Wohl Community Center — kids running everywhere and adults doing their best to keep up. Then, suddenly, out of nowhere, Jayson Tatum appears. Shrieks echo throughout the building. Jayson Tatum, the Jayson Tatum, the Boston Celtics player who people are calling the next all-time great, is walking through this recreation center in north St. Louis.

The entire place orbits around him. Kids, grandmothers, volunteer coaches, even babies and staffers. Everyone is running up to Tatum. Some want a photo. Some just want to see him in the flesh. The NBA star towers over everyone; his head looks close to hitting the ceiling, as if he no longer fits.

Tatum, now 24, was once one of these Wohl kids. Up until high school, Tatum traveled to Wohl multiple times a week from his home in University City. There was always something going on: a pickup game, a workout, a men's league game, kids shooting pool.

"That's just kind of how it was," says his mom, Brandy Cole-Barnes. "They don't turn anybody away."

As a kid at Wohl, Tatum saw his first Bentley in the Wohl parking lot, when two NBA players pulled up to play in a Pro-Am game, his mom says.

Now, Tatum is that NBA player, returning to Wohl multiple times a year. He paid for the basketball court to be refurbished and for a new computer lab. He also hosts an annual summer basketball camp. He even brought ESPN to the court for an exclusive interview.

"This," he told ESPN in 2021, standing in the Wohl Center, "is like my home."

On this Tuesday afternoon in August, Tatum is running a backpack drive, complete with Jordan bookbags, Beats headphones, notebooks, pencils, Chick-fil-A chips and Celtics hats. It's for Wohl kids –– and Wohl kids only. There's no press, no fanfare. Tatum's family is there, including his four-year-old son, Deuce, who chases a bouncy ball around the gym with Wohl kids.

Any rec center with Jayson Tatum to its name would have a lot to boast about. And Wohl does. Tatum's name is plastered on the hardwood floor that he donated. A banner in the gym reads, "Home of Jayson Tatum."

But there's also a wall-length glass case in the hallway, layered with foot-long trophies earned by former Wohl legends who went on to star in college basketball and the NBA.

Wohl, they say, is the mecca of St. Louis basketball.

The rec center has produced elite athletes: NBA players including Tatum, Larry Hughes and Patrick McCaw and college superstars including Torrence Watson, Courtney Ramey and Caleb Love, who recently led North Carolina to the March Madness finals. There are also countless local legends who never made the NBA but old timers still mythologize, like Antonio "Windmill" Rivers, whose head nearly hit the rim when he dunked.

This is a public rec center on the corner of Kingshighway Boulevard and Dr. Martin Luther King Drive, where the grass is unkempt and the rims seem a little too high.

Yet, somehow, it continues to produce some of the best basketball players in the world.

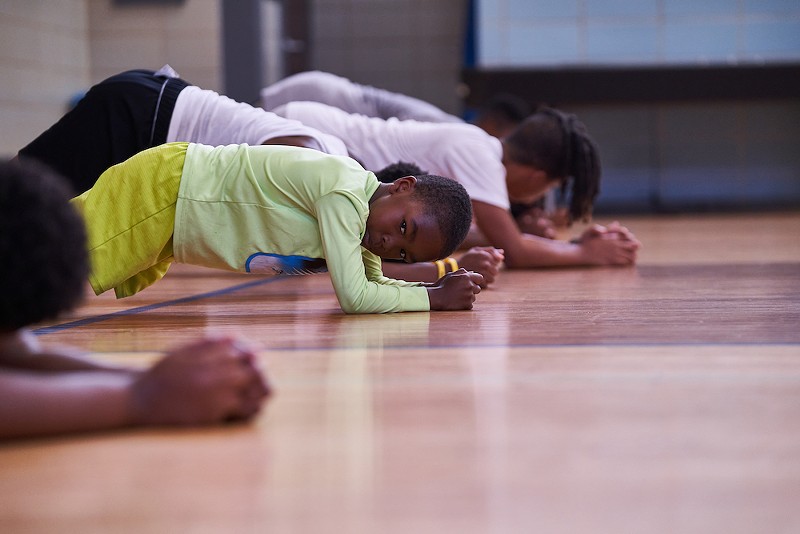

On Tuesday afternoon in the Wohl basketball gym, kids are screaming, coaches are yelling, balls are flying, parents are chatting, rap music is blaring and more balls are flying.

It's chaos.

On one half of the court, a coach is putting on a workout for 10 kids, ranging from ages 3 to 15. On the other side of the court, a coach is running a kid through a cone drill, but instead of cones, they're using a combination of disc slam containers and pool noodles.

It looks like a normal rec center, but it's not supposed to look like a normal rec center. This place is supposed to be the mecca of basketball. It should, at the very least, be neatly organized, right? Or at least have a shooting machine or a coach with innovative drills that no other coach has or maybe a high-tech movie room, where people can break down jump shots.

Instead, it has Michael Nettles, the man who coached Tatum and, well, everyone. He's 58 years old and often sporting red-and-white Air Force 1s, a large silver cross, Celtics sweatpants, multiple variations of Celtics flat hats, sometimes an earring and sometimes a toothpick. He's technically a city staffer, serving as a recreation leader at the Wohl Center. Really, though, he runs the basketball gym.

But on this day, Nettles isn't coaching. He's just sitting on the sidelines and talking. Nettles is always talking. He mumbles fast. He throws out names of former St. Louis high school basketball players as if everyone knows them. He goes on long tangents about basketball philosophy and St. Louis basketball history.

Nettles talks to everyone. He knows everyone, usually, by a nickname he gave them — Too Tall, Lil Steph, Slaughter, Mohawk, T Mo, not to be confused with J Mo.

While the chaos rumbles along, a six-year-old girl walks up to Nettles. She calmly places her foot on his knee. Without pausing his conversation, Nettles ties one shoe and then the other.

Who is that?

"That's my Wohl grandbaby," he says.

Nettles grew up in north St. Louis. His father was a trash man and also worked in construction. His mother was a nurse at Homer G. Phillips, the acclaimed Black public hospital that closed in 1979. They weren't sports fans. His parents preached waking up early and studying in school.

Nettles got up at 4 a.m., but he didn't always do well in school. He constantly picked fights with bullies, he says, getting him kicked out of multiple middle schools. "I disliked the bullies," he says. "I hated bullies."

As the years went on, Nettles calmed down. He found solace in sports and played basketball at State Technical College of Missouri before transferring to Harris-Stowe State University.

He graduated in 1988, taught in schools and then, in 1992, took a job with the city's Department of Parks, Recreation and Forestry. He clocked in at every rec center in the city, he says. He even worked in the Medium Security Institution, better known as the Workhouse, where he reimagined the recreation program, adding handball, basketball tournaments and other activities.

Then, in 1996, Nettles arrived at Wohl. And he ruffled up the status quo.

"I had to go through certain things," Nettles says. "'You grown folks can't have the gym all damn day.' Boom, boom, boom. So, hey, I kicked them out. Some people didn't like me. I didn't care."

Nettles can be a loose cannon when he talks — or as he calls it, he "raw dogs it." "You jack off the game," he tells one of his players. "Byron ain't shit," he yells in the air, with Byron standing there. But this is just jokes, Nettles' famous banter.

If the Wohl Center has a beating heart, it is Nettles. He instantly knows when someone new is walking the hallways. "Hey hey hey!" he'll call after them. Then, he'll ask for your name, your story and, probably, your parents. Then, you can get a workout.

Kids are always in the gym. Kids from the neighborhood, kids whose parents drive them from the county –– even kids who don't play basketball but just want a place to hang.

On an afternoon in early August, a mom who hasn't brought her preteen son to Wohl in weeks walks into the rec center.

"I ain't messing with him," Nettles tells her. "He ain't no Wohl kid."

He'll let the kid work out, of course, but not before taking an opportunity to crack jokes at the mom's expense. Nettles rarely leaves the north side –– unless he's going to a travel basketball tournament. Recently, he went on vacation. Asked where he went, he said St. Louis. Where else would he go?

"I don't talk to her no more," he says about the mom to the crowd of people on the sideline. "She wanna spend all that money in the county and then come back!"

"He's only been out there for a month!" she protests.

For Nettles, that's a month he was at Wohl working with Wohl kids. Nettles doesn't use that phrase lightly: Wohl kids.

Wohl, or "Wohls" as most people call it, isn't only a noun to Nettles. It's an adjective. A Wohl kid is someone who is there all the time, week after week after week. "They tough. They mental. They prepared for life," Nettles says.

When a new peewee kid walks into the gym, Nettles introduces himself. "Hi, I'm Mike," he says, shaking the kid's hand, introducing him to Coach Stephon — alumnus and volunteer coach Stephon King — and sending him into an already-in-progress workout with teenagers.

"I'm not like everybody else," Nettles says. "Like, I work with everybody. ... I don't care what you've done. I care how you treat me. If you for real what you for real then I'm for real what you for real."

One day, he's teaching a three-year-old how to shoot. The kid catapults airball after airball on a mini-hoop. Nettles keeps grabbing the rebound and handing him the ball. It's like clockwork.

Airball.

"Catch it, and do it again, baby!" Nettles says.

Airball.

"Catch it, and do it again, baby!" Over and over again, until the kid is tired and needs some water.

"You getting it up there now, baby!" Nettles says, beaming.

When Wohl was opened in 1960, it was lauded as the best recreation center in the city. Through a city bond and a donation from David Wohl, owner of Wohl Shoe Company, the new building featured a pool, kitchen, multipurpose room and an NBA-length basketball court.

"An architectural gem from entrance to exit," the editor of the American Recreation Journal wrote at the time, "the Wohl Center is one of the nation's outstanding buildings."

It was also the best place to play basketball.

That stretched back decades, though, before Wohl was even built. Before Wohl, there was Sherman Community Center, located up the hill in Sherman Park. With multiple basketball courts, its basketball box scores ran in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch as early as the 1920s.

"It was the main place to play basketball," says Ron Golden, who lived in the neighborhood in the 1950s.

When Wohl replaced the former center in 1960, it inherited that basketball culture. During the 1980s, the Jodie Bailey Super Summer League, considered St. Louis' first comprehensive area-wide high school basketball league, took place at the Wohl Center. In the 1990s, there was the Midnight League, with games anywhere between 9 p.m. and 1 a.m. It was designed to keep people occupied during the night when crime often took place.

"It was the biggest for basketball in St. Louis," says Derrick Murray, who grew up going to the Wohl Center in the 1990s and 2000s. "Everybody from everywhere was coming to the Midnight League."

In 1995, Corey Frazier was a rising freshman on the Saint Louis University basketball team. But before he even played a game of college basketball, a teammate made him play at Wohl.

When he arrived on a Sunday evening, he was confused about what made this place so special. The gym was dim, and the rims were too high. No one cared, or knew, about Frazier's pedigree as a prized recruit. His opponents talked trash, never let him call a foul and made him power through every bucket.

"I earned my respect in St. Louis that day," says Frazier, now a professional skills trainer.

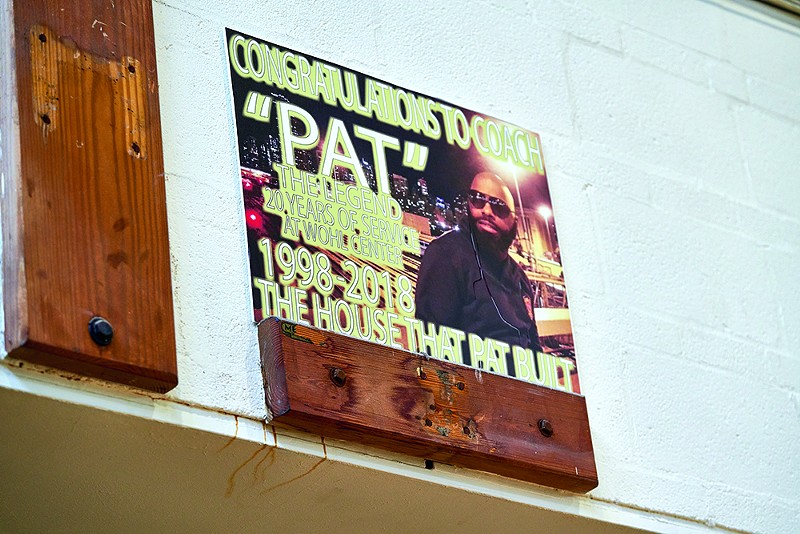

Then during the late 1990s, Wohl went through a rough patch, says Lamont "Pat" Johnson, who volunteer coached at Wohl for two decades. The Midnight League organizers were accused of stealing nearly $60,000 of donated money from the league from 1995 to 1996. Shortly after in October 1997, a year after Mike Nettles arrived, one of the rec center's most promising alumni, Sean Tunstall, who played at the University of Kansas, was shot and killed in Wohl's parking lot.

There was a "stigma around the Wohl Center," Johnson says.

Originally from the 12th & Park Recreation Center, Johnson started coaching at Wohl in 1998. Picking up his sisters from summer camp, he saw Nettles on the baseball field trying to train 20 kids in T-ball. Johnson, who'd served time in jail, recognized Nettles from his stint as a staffer at the Workhouse and offered to help. "I knew he couldn't teach all of them at the same time," Johnson says.

For two decades, Johnson coached at Wohl. Although he left in 2018 to return to 12th & Park, a banner hangs in the gym declaring Wohl "the house that Pat built." Over time, he helped Nettles organize workouts, in-house leagues, city-wide leagues and, eventually, travel teams that were separate from the Wohl Center.

In the 2000s, the gym had all kinds of leagues — high school leagues and women's leagues and peewee leagues. Mike Nettles would ref the games, and he pissed off everyone –– players, coaches and fans alike — because he rarely called fouls, and he rigged the games, so they would always end in a close score.

On a typical weekday afternoon, a sea of people crowded the gym. A line snaked outside of the kitchen and the smell of fries filled the air. There were never enough places to sit, and most fans spent the afternoons standing. Cars filled the lot, street and grass around the center. "If you could [park in the parking lot]," Miles Nettles, Mike Nettles' son, remembers, "you got a good parking spot."

Wohl always seemed to be open. The coaches held basketball activities on weekends and late at night. If there wasn't a league game, there was always pickup. And if you didn't like basketball, there were always programs outside of basketball –– karate, summer camp, dance, football, cheerleading and boxing.

Even after the rec center closed for the night, the older guys went to the kitchen to play dominoes or dice or pool. Kids would stay in the gym to shoot hoops.

Throughout it all, Nettles and Johnson, who was a full-time volunteer, stayed together and built Wohl's reputation as a training ground for youth players, with a focus on fundamentals. They forced kids to dribble with two balls, practice weaving through cones, shoot baskets with boxing gloves on and dance in the defensive stance to the "Cha-Cha Slide."

"I love Mike to death," says Tatum's mom, Cole-Barnes. "But even if it wasn't the most organized, if you didn't have enough advance notice, you knew if you showed up that, at some point, if there's enough kids in the gym, we're playing basketball. Mike is gonna go in the back and pull out jerseys."

Over the years, though, the neighborhood around Sherman Park experienced a dramatic population loss. Once a middle-class Black community in the 1960s and '70s, when Wohl was first founded, the area struggled through decades of disinvestment. Businesses closed their doors, houses became vacant lots, baseball fields grew weeds and crime increased. The city did little to reverse the neighborhood's decline. People left in flocks.

From 2000 to 2020, each of the four neighborhoods bordering Wohl lost population –– dropping by, on average, 38 percent. In Kingsway East, for example, the population fell from 3,797 to 2,355.

Quite literally, there were fewer kids in the community for Wohl to pull from. And they had fewer resources to provide for the kids that did stop by.

For decades, funding across rec centers in the city continued to decrease, says the city's recreation department director, Evelyn Rice. Staff members were laid off. Some rec centers had to close over the weekend. Others shut down altogether. In 1960, for example, when Wohl was first built, there were more than 10 city recreation centers. Now there are only six.

That's changing now, little by little. Under Mayor Tishaura Jones' administration, funding has increased, with an influx of ARPA funds, allowing the centers to re-hire staff, open during the weekend and bring back programming, such as singing, dance, photography and maybe even another version of the Midnight League.

But even during those "lean years," Rice says, she would drive by Wohl when it was "closed" for the weekend, only to find it open. There would be Nettles coaching or Dana Moorehead, the recreation center director, watching kids.

"When the staffing gets cut, then you can't offer programs as frequently," she says. "You can still do basketball but not to the level and extent you want to."

She pauses.

"Unless you have somebody like a Mike Nettles, who does it anyway."

Mike Nettles still wakes up at 4 a.m. He takes a shower, watches the news and, by 5:45 a.m., he's driving to his day job in west county, where he arrives by 6:30 a.m.

By day, Nettles is a behavioral specialist at CenterPointe, where he works with adults who are dealing with detox, depression, suicidal thoughts and addiction.

He leaves CenterPointe at 3 p.m. and drives straight to the Wohl Center, where he's supposed to work from 4 to 8 p.m. as the program director. But normally, he stays until 9 or 10 p.m. It amounts to a near 15-hour workday. When he's done, he goes home, spends time with his wife and watches ESPN, Blue Bloods or Criminal Minds.

Sitting in the rec center, looking over the basketball court, Nettles reflects back on his years at Wohl.

"Now I'm old enough to say I apologize to the ladies that I dated," he says. "We never broke up because of me cheating or something like that. It was just quality time."

Does he feel like he's missed out on life — relationships, kids, TV shows, sleep — because he's always at Wohl?

"No no no no no," he says.

"Actually," he says, pausing. "The honest truth, and I'll probably get teared up with this..."

This is surprising to hear him say. His son, Miles, said he has never seen Nettles cry. But there's a story Nettles carries with him — a story that even his son might not know. It's "the reason," Nettles says, "that I do what I do."

Back in the 1980s, when Nettles was in his 20s, he returned to St. Louis after junior college. He met up with friends, who had all played on the same childhood basketball team.

They started drinking — and people opened up. "What I learned was, when somebody drinking, they all tell — the what? — the truth," Nettles says, answering his own question.

That night, some of his teammates confessed that they had been molested by their childhood coach.

"I don't know what — something just came on me," he says. "I just say 'Look, I'm gonna coach all the kids ... I'm gonna know everything. I'm gonna see everything. I'm gonna pay attention.' It was just something that I had to do. I want the kids to have everything. I want to make sure these kids are safe."

He pauses. Only two people in the world know this story, he says.

"It's why I joke with these kids," he continues. "It's why I have conversations with these kids. In the huddle, we talk about life. Do you feel uncomfortable at home? Who is this guy? That's why anybody who come in here, I already know."

Nettles says he doesn't care about winning or losing — unless it's a playoff or tournament. Basketball is about molding adults and training kids for life's setbacks.

Lots of coaches pay those ideas lip service. But Nettles really doesn't seem to care if his team wins or loses. Either way, he's still going to be at Wohl, and either way, he's going to invite kids back for a free workout. If he cared about winning, he would be coaching all the time instead of sitting on the sideline, yelling "Byron ain't shit!" or running T-ball practice. He drives kids home from workouts, gives shoes to those who don't have them and lets families crash at his place when they need somewhere to stay.

Back in north St. Louis in the 1960s and '70s, a village built Mike Nettles, he says. "Everybody took care of everybody," he says. And it's a village that Nettles builds, volunteer coach by volunteer coach, parent by parent, peewee athlete by peewee athlete, Wohl kid by Wohl kid. For all of the work he does, there are other Mike Nettles coaching football, baseball, boxing and organizing non-sports programs. There's Ms. Dana, the head of Wohl, who oversees everything, so that Nettles can focus on the basketball gym.

"It's a wonderful place," says Rice, the city's recreation director. "It's almost like church."

It's not money, not special drills that built Jayson Tatum. It was this village and the quality time missing from Nettles' previous relationships. It was all spent here, at Wohl, allowing Tatum and so many others to become some of the world's best basketball players.

Toward the end of one of these 15-hour-long days, a little girl walks up to Nettles, who's seated on the baseline. She's about the height of Nettles in his chair.

"Mr. Mike Nettles," she says.

Nettles, yelling across the gym, doesn't seem to hear.

"Mr. Mike Nettles," she says again in a soft voice.

He turns to her and looks her in the eye. His hands are folded in his lap, patiently waiting.

"You're at work," she says, with a sly look. "Why do you have on slides?"

"I'm not at work," he shoots back. "This is where I live."

Since COVID-19, Wohl hasn't been the same. Because of the pandemic restrictions, pickup games were cut, and the leagues have shrunk. Maybe that will come back in the future. It's not clear. Nettles says he's "easing it back."

There are still adult leagues at Wohl, including a 40-and-over league, but most of the leagues and pickup moved away from Wohl. Now, Nettles runs high school leagues at Tandy Recreation Center or Cardinal Ritter College Prep. This way, people like Coach Stephon can run workouts for six-year-olds at Wohl, and Nettles can run a league for high schoolers at Tandy.

"You need multiple gyms to try to help everybody," Nettles says. "If we keep everything at Wohls? Wohl's area is good. What about Gamble [rec center]? What about 12th & Park? What about Tandy?"

But that doesn't mean Wohl is empty. Summer camps fill the building all summer. Boxers pound bags upstairs, and students study in the computer lab.

Nettles has a stable of volunteers who run workouts at Wohl during the afternoons and evenings. One of those people is Stephon King, Coach Stephon, Nettles' former player, who still looks like he could be a Wohl kid at 28 years old, with a little scruff covering his youthful face.

For the last seven years, King has been coaching at Wohl. He has a wife and kids. He works a full-time job as a manager at QuikTrip. "In my spare time, I come here," he says, laughing. "Which is a lot of time." On a regular basis, his kids, wife, mom, nephew and older brother watch him coach from the sideline or participate in the drills. His son, Lil Steph, zig-zags from basket to basket like a wind-up toy in a black tank top. The ball appears bigger than his body, but he slingshots it from his hip and it goes in, a lot.

King has been coming to Wohl since — well, he doesn't really know. Maybe since he was three? His mom needed somewhere to send her kids. Everyone in his family went here. It's where they hung out with friends, shot pool in the multipurpose room, took karate class and played basketball. He was coached by Nettles, Johnson and anyone else who showed up. "We was just here," King says. "And that made us better."

Even when King moved away from the area, he took the bus every day to Wohl. If he couldn't catch the bus, one of the coaches picked him up.

"This is my home," King says. "I say my home was my second home. This is my first home because I was here so much."

But it's more than just a basketball facility. Leave the gym at 7 p.m., while the sun is setting over Wohl, and boom. You'll see people everywhere. Quite literally everywhere. There won't be an empty spot in the parking lot. Little girls dance and yell in high-pitched voices against a rec-center wall during cheerleading practice. Parents watch peewee football. Little-league players field ground balls on baseball fields sprouting weeds. Kids climb on the playground. Adults lean against their cars, smiling, chatting and reminiscing.

In the heart of north St. Louis, where outsiders say crime is rampant, homes are vacant and parks are dangerous, the Wohl Center buzzes with life.

It's 7 p.m. and the Jayson Tatum backpack drive is coming to a close. Tatum has left. His family has left. Volunteers are packing up the extra bookbags and folding up tables.

But Nettles is sitting in the stands, talking with his wife.

It's hard not to think that, with a player like Jayson Tatum on his resume, Nettles could be anywhere. Maybe a college coach, a professional trainer, or at the very least, a high school coach. No one would think twice if he left. That's what you're expected to do.

Wohl kids go off to college, some make the NBA, some become boxers, doctors, lawyers, construction workers, barbers, but Nettles sits in the same place he has since 1996.

When asked if he'll be at Wohl forever, he squints as if he's confused by such an outlandish question.

"Yeah yeah yeah yeah," he says. "Guess what though? If I hit the lottery, I ain't going nowhere. Here it is: If the good Lord took me today, I'm not mad at him because I really enjoy life."

Kids start to run on the court. Their legs are dragging, and their arms are flopping. Celtics green-and-white balloons still float above their heads.

After the kids do a few suicides, Nettles appears on the baseline.

"You should have a ball in your hand at all times!" Nettles says, raising his voice. He points at each player. "You should have a damn ball, and you should have a ball! So go get a ball out my rack, dude!"

Jayson Tatum is gone. And that means the Wohl kids –– and Mike Nettles –– are back to basketball.

This story was updated to correct the spelling of Lamont "Pat" Johnson. We regret the error.