The flight of Elliana Grace the Human Cannonball closes the first act of The Greatest Show on Earth, and it lasts less than a minute, from the moment she slides into the mouth of the cannon to her final bounce into the safety of the oversize air mattress she uses in lieu of a net.

"Do not blink," bellows ringmaster Andre McClain as she disappears, "because this memory of a lifetime will be over in one! fleeting! flash! of glory! Elliana! Are you ready?"

"Yeah!" comes a small voice from the inside of the cannon.

"Everyone count down with me!" McClain yells. "In FIVE! FOUR! THREE! TWO! ONE! Gooooooo!"

In a flash of fireworks and an explosion of cheers, she pops out of the cannon, a young woman in pink spandex and pink superhero boots, arms outstretched, body held tight and straight as she soars across the ring, up, up toward the ceiling, her long, dark hair streaming out behind her.

Her eyes are wide open and focused on the four-foot-deep air bag on the other side of the circus ring. Her body somehow knows when it has reached the top of its trajectory. She flips, just once — body still straight, arms still outstretched — and falls backward toward the air bag.

The Human Cannonball doesn't usually remember much about each flight, aside from a quick impression of soaring through the air. On the other hand, she has just been shot out of a 24-foot-long air-compression cannon and travels between 75 and 100 feet at a force of 7 g. That's greater force than a roller coaster, greater than a Formula One racecar, greater than the space shuttle. A force powerful enough to have caused some human cannonballs to pass out midflight. This has never happened to Elliana Grace in more than 100 shots since she took the job last October. Still, she's in the air approximately three seconds. How much would you remember?

The Human Cannonball's memory is all in her muscles. As she lies in the cannon, listening to the countdown, she tightens them all — legs, core, neck — until she feels perfectly straight, like an arrow that won't slow down or blow off-course, and she prepares to hold herself that way for the next five seconds, no matter how far or how fast she flies. Not everyone can do it. (Not everyone should try.) But the Human Cannonball has been preparing for this for almost her entire life.

She lands spread-eagled, flat on her back and bounces gently. A group of spotters rushes to meet her and help her clamber out of the air bag. There she is, back on land, arms up, head back, one foot placed carefully behind the other. Ta-da!

And thousands cheer.

In the seats, Jessica Hentoff, the Human Cannonball's mother, finally relaxes. She no longer watches the act through a camera lens, taking photos instead of watching the performance directly, as she did when the Human Cannonball was still in training. Hentoff is a former circus performer herself, a founding member of Big Apple Circus and St. Louis-based Circus Flora, and currently the director of Circus Harmony at the City Museum. She had been teaching her daughter tricks since she was an infant. But this act is slightly different from the high wire or trapeze. It's more...volatile.

"It worries her a little," the Human Cannonball explains, "because she is a mother, and I am getting shot out of a cannon."

The first time Elliana Grace Hentoff-Killian climbed into a cannon, on her first day at work for Ringling Bros., she fell asleep. It wasn't that she felt a particular ease or affinity with the cannon. She was just tired. It had been an intense few weeks since word had reached Hentoff through the tight-knit circus community that Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus was looking for a new Human Cannonball — did she know anyone who was interested and available for a two-year commitment? As it so happened, Hentoff-Killian had recently returned to St. Louis after a disappointing nine-month stint at École de cirque de Québec, a prestigious circus school in Quebec City, and was working as the lead aerial coach at Circus Harmony.

So Hentoff-Killian flew (in an airplane) to Rochester, Massachusetts, where Ringling Bros. was on tour, to audition.

"The audition was a lot of fun," she says. "Well, fun for me. It was a lot of high falls. They started pretty low, fifteen feet, and then got higher. The last one was 35 or 40 feet. I'd jump into the air bag. They wanted to see if I could land correctly and keep the right body position, and if I took direction well."

There was an interview, too, during which Hentoff-Killian wore a suit and proved she could speak articulately to reporters and the public. She got the job, signed a two-year contract and began training. At twenty years old, she was the youngest Human Cannonball in Ringling Bros. history. (Also, as her mother takes great joy in pointing out, the first Jewish Human Cannonball.)

It wasn't until a few days into her new career, when her trainer told her she was going to take her first shot the next morning, that she became terrified.

Hentoff-Killian is built like a gymnast: petite and muscular, with a sweet face and twinkling brown eyes. She looks like she ought to be sitting in a sociology lecture taking copious notes. But she was practically born in the circus ring.

"I was in Circus Flora when I was two weeks old," she recounts. "My mom had a two-week maternity leave, and then she went back to work, and I was the baby. I got passed around the ring."

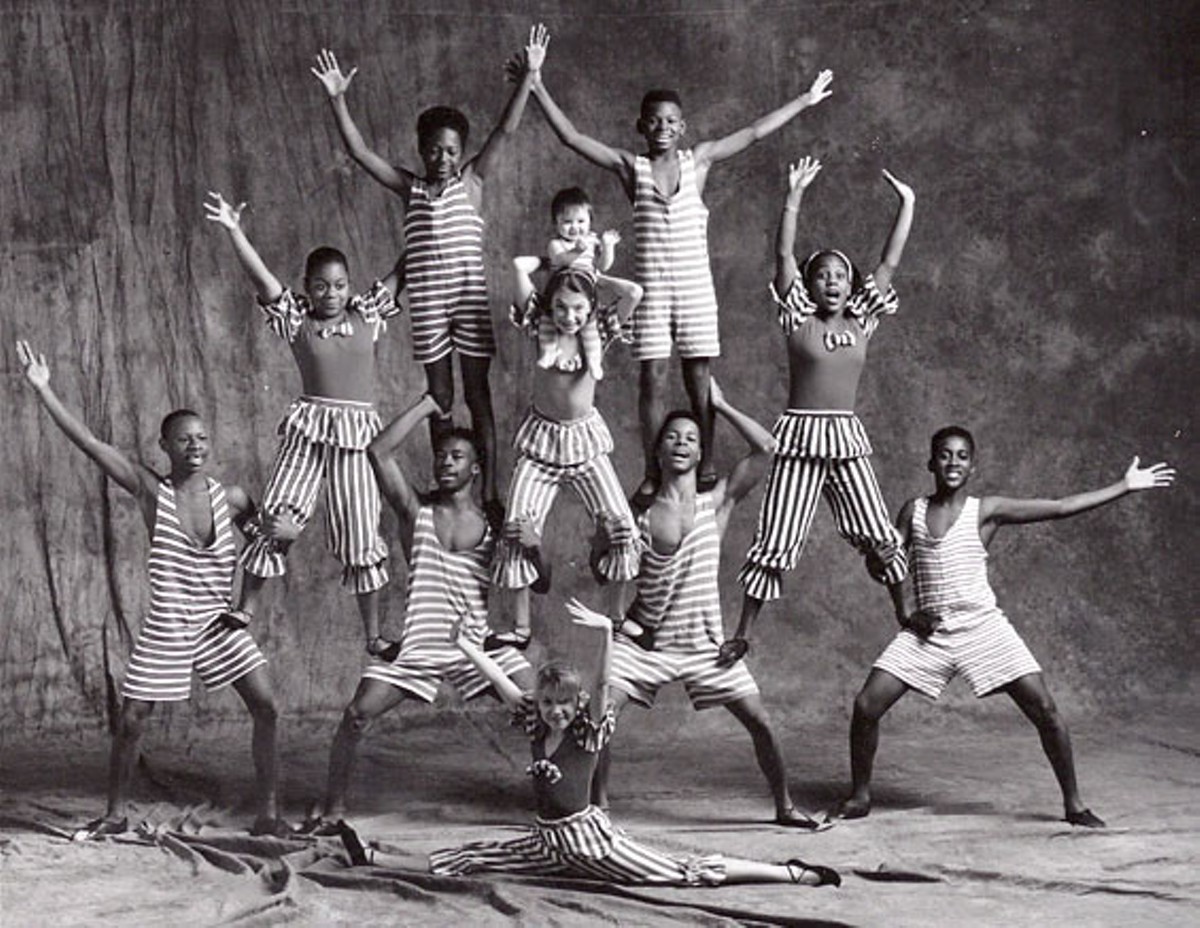

Jessica Hentoff's work at the time was to do an aerial act at Circus Flora and to teach juggling and trapeze and unicycle to kids at Circus Harmony, a "social circus" that combines the circus arts with community outreach. (The idea is that if you bring people from different backgrounds together to perform in a circus, which requires trust and teamwork, it will lead to understanding and harmony — hence the circus' name.)

"Elliana came up from birth," Hentoff says. "She did her first trick when she was six months old. It was a baby balance. When you push a baby's legs, she can stand up. Elliana stood in the hands of a clown."

By nine months Hentoff-Killian was an honorary member of the St. Louis Arches, Circus Harmony's elite performing troupe. In short order she began taking classes herself. The first trick she remembers performing was on the Spanish web, an aerial rope apparatus. She dangled by her hand from a loop in the rope then flipped her legs over her head and started spinning as fast as she could. She was six years old.

By then her mother had given up the trapeze — she says it took five years for the calluses to disappear from her hands — but not the circus. Growing up, Hentoff-Killian and her two younger brothers (Keaton, now eighteen and a high-wire walker; and Kellin, sixteen, a juggler) spent more time under Circus Harmony's glass big top in the City Museum than they did at home in St. Louis, near Maplewood, or, later, in Florissant. All three were homeschooled. None of them minded. Circus was all they ever wanted to do.

At one point their father, Michael Killian, suggested the boys go out for ice hockey. Hentoff put the kibosh on that immediately. "In youth hockey," she explains, "all the jerseys have stop signs on the back to remind the kids not to bash each other in the head. That's not what I want my kids doing. The professional model of circus is people working together."

It's Hentoff's dream that someday circus will replace soccer in the pantheon of youth activities.

The future Human Cannonball spent her childhood and teenage years in the ring and in the two practice rooms backstage. The ring itself is a circus in miniature: twenty feet in diameter (most traditional circus rings are forty-two feet across), with a seventeen-foot-high ceiling, about twenty feet too low for the flying trapeze. There is also no cannon, partially because of space constraints, partially because, as Hentoff puts it, "Insurance companies flame out on the cannon thing." But Hentoff, who presides over the space like a combination of drill sergeant and Jewish mother, expects her young performers (including — especially — her "biologicals") to act like professionals. And if they don't practice or do their chores, they don't perform.

The circus performs more than 300 small shows a year, on weekend afternoons in the winter and every day during the summer, plus a full-scale spectacle every January. There's nothing about a Circus Harmony performance that says "kiddie circus." The performers are young, but the tricks are real and impressively difficult. And if someone drops a juggling club or falls off the high wire, she picks herself up without any fuss and tries again.

"Most people, when they hear Circus Harmony is a kids' circus, think: 'Oh, we'll go see the kids, it'll be cute,'" says Richard Kennison, who teaches juggling, acting and balancing. "Then they go from 'Awwwww' to awe."

Hentoff-Killian mastered the circus arts: unicycle, juggling, tumbling, high wire and, during Circus Harmony's appearances at Circus Flora, bareback riding. Her specialty, though, as she grew older, was aerial, particularly the lyra, a steel hoop that hangs above the ring. With her partner Claire Kuciejczyk-Kernan, she perfected a double-lyra act, during which Kuciejczyk-Kernan would hold herself up on the hoop twelve feet above the ground while Hentoff-Killian would wind her legs around her partner's and slide down head-first until she hung suspended only by their joined feet.

"They would catch the trapeze with their toes," Hentoff remembers. "How can I say, 'No, you can't do this'? I did aerial, and I was fine."

This reaction, it must be noted, is far more sanguine than that of Hentoff's own father, the jazz critic and former Village Voice columnist Nat Hentoff, who described his decade-long boycott of Jessica's performances in a 1986 essay for the Wall Street Journal. "We argued bitterly and raucously in my long-distance attempts to get her to stay on the ground," he wrote. After Jessica suffered a 30-foot fall, Nat bought her a net, which she never used. Finally Nat gave in and went to see Circus Flora and was converted: "Once the act began, I became so involved in the choreography that I forgot to be afraid."

Hentoff is aware that, given the family history, and also her role as Hentoff-Killian's teacher, it would be hypocritical of her to avoid the Human Cannonball act. She mothers her daughter in other ways: She used her circus connections to conduct a background check on Brian Miser, the man who would be training Hentoff-Killian on cannon, and she traveled to Boston to watch the early training sessions and to Tampa for the circus' opening night. And like many mothers, she brags about her daughter's exciting job and takes some credit for her success. "I trained her," she says, "so she could physically do this."

Circus is beautiful. It is amazing. It also hurts. A lot. Your muscles ache from being used in unexpected ways. Your hands blister from gripping the bar of the trapeze until you finally form calluses. You get banged on the head with juggling clubs, and, should you manage to catch them, they can tear your fingernails out.

Circus tricks, however, are often not as death defying as they appear. Hentoff cites studies that show that kids in circus-arts programs are injured far less frequently than kids who play sports. Those results may be skewed by the fact that there are simply fewer kids who take circus classes, but Hentoff says that since she began teaching circus in 1989, she can count the number of injuries on one hand, and that none was more severe than a broken wrist.

"It's what you're willing to put up with," Hentoff says. "Tricks are based on natural behavior. If the body couldn't do it, you couldn't do it. It depends on how much you want to push your body. Desire trumps talent."

"With [Hentoff-Killian] it was way more about desire than talent," remembers Karen Schellin, Circus Harmony's general manager. "For one of the shows, Elliana did the loop walk. There's the bar with rope loops attached. She hangs by her ankles upside-down and then puts her foot in the next loop. It's like walking upside-down. I watched her practice with bloodied, blistered ankles. She worked through the pain. It was desire more than anything else."

Getting shot out of a cannon is the hardest trick Hentoff-Killian has ever had to master.

"The pain is hard to describe," she says. "It's like you wake up with a 'whaaaaat-did-I-do-last-night?' kind of hurt. I was using new muscles and learning new body controls. My body was not happy with me."

There was also getting her head around the fact that she was going to have to get shot out of a cannon once, twice or three times a day for the next two years.

Circus performers tend to speak in vague bromides about their ability to pull off impossible-looking tricks. They say things like, "Mostly it's knowing you can do it." And maybe there's no other way to explain it. For weeks you're riding a unicycle alongside the City Museum's Tiny Town, hanging onto the railing, practicing tightening your stomach muscles, aligning your hips and shoulders just so, learning how it feels to do it properly, until one day you realize you don't need the railing anymore.

But what sort of practice prepares you for getting shot out of a cannon?

Hentoff-Killian considers herself fortunate that she only had to worry about that for a single sleepless night. "I knew I'd have to do it eventually," she says philosophically.

It felt very different, though, lying in the cannon before that first shot. It was to be a short, low shot, just so she could get the feel of it, but still. She was about to be shot out of a cannon.

I have to tell them "go," she thought, and I don't want to tell them.

She did not think of the loop walk, or the lyra, or any of the other tricks she'd mastered. Instead, she thought of the contract she'd signed the week before, and of how badly she wanted the job, and how she wanted to prove to herself that she could do it.

If I want it so bad, she thought, I have to do it. So all right. Here I go.

After the first shot, she was sure: She never wanted to do it again.

"The physical part is hard," she says, "but the mental part is harder. I take the attitude of mind over matter, but this is matter over mind. You have to let it do its thing and go along for the ride."

It was the contract that made her climb back into the cannon for another day of training. But a funny thing happened that second day, after she took her third-ever shot, the first one that went the way it was supposed to.

"It was amazing! It makes the bad shots worth it. I was hooked. I'm flying! It's like being on a roller coaster, except without the stomach drop."

The history of the human-cannonball stunt is rife with stories of death and debilitating injury, beginning with the very first human cannonball, a fourteen-year-old girl known as Zazel who took her first shot at London's Royal Aquarium on April 2, 1877, and went on to break her back a few years later when she missed the net while performing in P.T. Barnum's circus. ("Where were her parents?" Hentoff frets.) Over the years at least 30 more human cannonballs have been killed in action; the most recent, Matt Cranch, died in 2011 in England when his net collapsed.

Hentoff-Killian thinks occasionally about this and about what could happen to her if one of her own shots goes wrong. But she has faith in the air bag, which is large enough to catch her if she goes slightly off-course, and in her own ability to calculate the correct angle at which to position the cannon, a formula that takes into account distance, force, her own weight and even the air temperature inside the arena.

"I would really, really have to mess up calculations to miss badly enough [not to land on the air bag]," she explains. "It's hard to do on accident, unless a mechanical failure happens to the cannon itself."

Every performance begins with a cannon check, to make sure that nothing has gone awry overnight and that everything is as it should be, and then the positioning of the air bag, which the Human Cannonball does herself. There's also this precept from her mother: "If you get hurt, it's because you made a mistake or your partner made a mistake, or there was a problem with the rigging, which you were supposed to check anyway."

So far she has been injured only once, bloodying her nose when she accidentally kneed herself during practice. She called her mother afterward. "I messed up," she said, "but I wanted to do it again right and then call you."

This week the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus plays Brooklyn, New York. Hentoff-Killian lives with 300 other circus performers and staff, plus horses and elephants, on the milelong circus train, where, by virtue of her job as the Human Cannonball, she's been assigned a single room with a kitchen and private bath and her own washer and dryer.

Circus days are long, starting with a 9:30 a.m. call for costumes and makeup if there's a morning performance, not ending till midnight on a good night. She eats her meals with the other performers on the train's dining car (called Pie Car) or, if the arena happens to be in a city, in nearby restaurants. The Human Cannonball tries to stick to a balanced diet, low in carbs and high in protein, but she doesn't manage it as often as she feels she should. She stays in shape by running and stair-climbing before each shot and by doing the regimen of conditioning exercises — sit-ups, stretches, elaborate pushups — she learned at Circus Harmony. She tries to get eight hours of sleep a night and makes up for deficits on travel days.

Human cannonballs have longer careers than one might expect. Hentoff-Killian knows some who have been working for more than seventeen years; her teacher, Brian Miser, has been getting shot for ten years (sometimes while on fire).

While Hentoff-Killian is not opposed to taking longer flights in the future, once she gets more comfortable with the cannon, she's not sure if she'll ever want to fly while in flames. "You have to hold your breath when you're on fire," she says, "and I like to breathe."

She has been branching out in her circus duties. Before evening performances, she participates in the preshow where audience members get to come into the ring and meet the performers: The clowns do a special act, the horses come out, and one of the elephants makes a painting. Hentoff-Killian hands out Greatest Show on Earth temporary tattoos and talks with little kids. Sometimes she tells people that she's the Human Cannonball. The reactions are mixed.

"The kids think it's supercool," she reports. "The adults think I'm insane."

"She's a real-life superhero for the kids," says Nicole Feld, a Ringling Bros. producer who had a hand in hiring Hentoff-Killian. "But she's also someone the audience can identify with."

To alleviate the pressures of being the Human Cannonball, Hentoff-Killian asked to be part of a second act: In the show's second half, she rides an elephant.

"It's a treat for myself after every shot," she says. "It's the coolest thing ever."

The circus moves on every week or so. Aside from her time at school in Canada, this is the longest she has ever been away from home. She won't return to St. Louis until Ringling Bros. plays the Scottrade Center in October, when some of the performers from Circus Harmony will join her in the ring during the preshow. "You have no idea how excited I am," she says.

Back at Circus Harmony, she has not been forgotten. During intense conditioning class, students make what they call "Elliana noises," inarticulate grunts of frustration meant to circumvent Hentoff's strict no-swearing policy. This year's big Circus Harmony show, Capriccio, was dedicated to Hentoff-Killian and two other alums who've gone on to professional circus careers; the program featured a photo of Hentoff-Killian in full Human Cannonball girl-power regalia waving triumphantly from atop the cannon.

And of course her mother can't resist a little bragging, even in the middle of a Sunday-afternoon circus during which she's serving as ringmaster, when she takes a minute to announce that one of Circus Harmony's most illustrious grads is now a member of the Greatest Show on Earth.

Even so, she's still a little amazed.

"I never imagined she would do this," Hentoff says later. "Elliana's proof that you can grow up to be a Human Cannonball.

"Anything is possible."