In September 2020, 36 boxes of master reels showed up on Jim Varagona's front porch. They belonged to a dead man named Pep — Peter E. Parisi.

The boxes were moldy. They'd sat in the possession of Parisi's girlfriend, Linda Vaughan, for eight years before her death in 2010. Some of Parisi's friends believe Vaughan locked him in a room for days, withholding his insulin, which induced a diabetic coma that ultimately killed him in 2002. (Vaughan denied these allegations and there was never an investigation. )

Varagona moved the boxes into his basement "because having the remaining legacy of Pete Parisi in your living room, no matter how important we find it, can be overwhelming, especially for my wife." After Vaughan's death, the quarter-inch masters of Parisi's World Wide Magazine became the duty of Vaughan's daughters. The daughters reached out to Varagona's YouTube channel, and that's how they found their way to his porch.

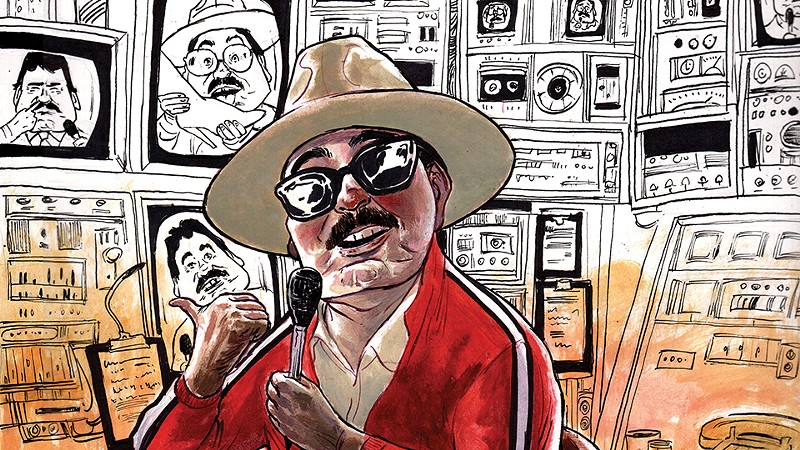

Varagona is the preeminent archivist of World Wide Magazine — a St. Louis public-access cable-TV show that was neither worldwide, nor a magazine.

Instead, World Wide Magazine is a hypnotic portal into late-'80s St. Louis; a crack in spacetime where viewers peer into the minds of south-city hoosiers from days gone by. It is the masterpiece of an outsider artist: a radio host turned County Cab driver named Pep, with a whiny carnival-barker voice and a genius for video editing. For 15 years, World Wide Magazine put out an episode per month where Pep took late-night tube viewers through a city in long-term economic decline. It was a universe where the center of the earth lies between Grand and Gravois and was hosted by an ensemble cast of St. Louis characters who, as the World Wide tagline goes, just want you to watch! "An audience of 50,000 hoosiers can't be wrong!"

Born in New Jersey in 1947, Peter Parisi attended three years of Emerson College before dropping out to move to Massachusetts and become a disc jockey. He followed that career to St. Louis to work with "Radio Rich" Dalton at KADI-FM. Dalton said Parisi was "more of a beatnik in appearance than a hippy." Parisi DJed the 7 p.m.-to-midnight slot, but outside of work, spent hours driving around in his Pinto, listening to the radio for fun. As program director, if Parisi didn't like something he heard, he'd pull over and bug Dalton about it from a pay phone.

In 1981, Parisi was fired after 10 years at the station. Money and relationship problems soon followed, and a few years later, he divorced his wife around the same time he purchased a camera. For work, he began driving a white and red County Cab with the custom license plate PEP.

The first episode of what would become World Wide Magazine was an hour-long program recorded in August 1985 called "Every Day I Use Up a Years Worth of Luck." After a hand-drawn title screen, the first piece of footage reveals three pink Oscar Mayer franks circling the water of a toilet bowl. "Next time I eat hot dogs, I guess I'll have to eat them a little bit slower," Pep (a.k.a. Mr. Entertainment) sighs. Cut to Parisi eating one of the wieners: "Eh, they were better last night."

Thus, the chaotic genius of World Wide Magazine was born.

At first, Parisi hosted the show as the city's cab-driver tour guide. Parisi made fun of St. Louis, but concerned himself with the regular people he drove around. Soon, the show downplayed the cab element and took on the format of picaresque interviews with horsing-around comedy skits. "How many Wash U students does it take to change a light bulb?" Parisi asks while visiting the Danforth Campus. "Five. One to change it, and four to call their parents for more money."

The show opens with the splashy 1930s jazz song "Tiger Rag" by Fletcher Henderson, because Parisi himself scored everything with his extensive record collection. "Back in the 1930s and '40s, people liked things hard and heavy," Parisi says during one segment. "Right now [in the '80s], people like things light. Light beer, light cream, light butter. All kinds of stuff is light nowadays. All kinds of people like their music light and bright." From his love of jazz and ragtime music to his wardrobe of suits and fedoras, Parisi himself has a Blueberry Hill-style nostalgia for an era long past, which may be why he responded to St. Louis so creatively. But Pep's nostalgia didn't extend to pious conservatism.

In 1996, when Pope John Paul II visited St. Louis, many St. Louisians complained that his holiness drove too fast for how many hours the crowds spent waiting for him. Parisi's response was to play the Speed Racer theme over footage of the popemobile hurtling down Tucker Avenue. To top it off, Parisi added footage of a soldier firing a semi-automatic rifle — spliced in to suggest a possible assassination of the holy father.

World Wide Magazine is inflamed with contradictions. The show regularly covered the annual Gay Pride Parade in the Central West End and the protests that broke out after for the police treatment of paradegoers. World Wide cameras went to the Veiled Prophet Parade and heckled the figurehead, asking if he was trying to start a race war. Parisi and the crew covered Klan meetings, shot fundraising promos for the restoration of Tower Grove Park, did multiple episodes on the fallout of the Great Flood of 1993, and interviewed attendees of the Louis Farrakhan convention.

One of the regular contributors to World Wide Magazine, Don L. Wayne (a.k.a. Black Jesus), found many of Parisi's portrayals of African Americans unacceptable. The show had a call-in number, and Wayne's gravelly voice got featured in a few episodes accusing Parisi of being a bigot. Later, Wayne appears on camera as Black Jesus. "Racism is for the birds and has no place in society. Or world society," Wayne said.

This was a mixed bag with Parisi. On the one hand, World Wide Magazine gave Black Jesus a platform to educate white people on the deep racial problems in St. Louis, and Wayne got a platform to expound upon his belief that Jesus was African. But, Black Jesus was introduced as the show's "crack reporter — or rather, reporter on crack." Wayne was an addict and open about it on camera.

Fellow African Americans in St. Louis complained about Black Jesus on the show as a representative of the community. That didn't get in the way of Wayne covering important subjects like the Schweig Engel protests. Schweig Engel was a furniture store that preyed upon poor people, encouraging debtors to rack up credit purchases they could never pay off. Black Jesus and Pep covered a protest of the store alongside the lifelong civil rights activist Jamala Rogers.

Parisi created a lot of problematic content for World Wide Magazine.

In his segment titled "One Man's Opinion," Parisi whines about people buying pork rinds with food stamps, and wonders why he's never seen an African American person with a tattoo. "Do they have more sense than to get a tattoo? Or does it not show up on their skin?" he wonders to the camera, completely alone, with no intention of following up. Just being a dick — a role Parisi sometimes embraced.

One fan of the show remembers seeing Parisi on the street. He stopped her and her friends for an interview, and the first question he asked the girls, who were all underage, was, "Do you prefer manual or mechanical stimulation?"

"I think Pete alternates between being brilliant and being an idiot," Vladimir Noskov said in a 1997 article, and repeated in a February 2022 interview. "It pains me to watch half of his show, but the other half is hilarious stuff." Noskov (a.k.a. the Mad Russian) is a legend in his own right. He worked on World Wide segments, and starred in many. In a recurring stoner bit, Noskov dances with a pair of women who tell the audience over and over, "I hear disco's making a comeback in this town." In Tower Grove Park, in front of White Castle, in the parking lot of Mr. Wizard's.

The primary question of World Wide Magazine was, "What does St. Louis mean to you?" Parisi did a special episode on the question. He and a cohost ran up to cars stopped at the intersection of Grand and Gravois, the "crossroads of the world," according to Parisi, and asked people sitting in their cars the question. "Love," says one woman. "St. Louis means the world to us!" shouts an enthusiastic driver with two other men in his truck. "KSHE especially," adds his friend. "I growed up here," the driver interjects as the camera zooms in on his excited, somehow innocent expression. They peel off screaming, "We love St. Louis!"

Much of the show ended up being "hoosiers doing what hoosiers do," according to Noskov. Parisi gave Noskov full creative run of his own segments, and the Mad Russian used that freedom to cover subjects like the first annual lesbian kiss-in at Union Station — which exercised the right of St. Louisans to express public affection and gave Noskov the opportunity to poke fun at stodgy local attitudes.

The idea of public access is about democracy; providing a platform to people who would otherwise never be heard. It's an exercise in free speech to take World Wide Magazine down to the Pat Buchanan rally, for example. "Do you prefer Hitler or Mussolini?" the Mad Russian asked Buchanan in the middle of a speech. "Who's worse? Jews or Blacks or Mexicans?" Noskov asks, a recorder slung around his shoulders, as audience minions gather round to escort him and the cameraman out. "What's the best thing about Hitler?"

The Buchanan clip and many others were sent off to The Howard Stern Show and played on the air. "He's got brass balls," Stern said. "'Cause these Pat Buchanan people looked like they were going to rip his head off. They were not digging him at all."

"I guess I'm a moron to be doing World Wide Magazine at all," Parisi said in a 1997 article in the St. Joseph News-Press. "It causes me so much pain." The article's headline read, "TV Producer Battles Cable Companies to Air His Show." Despite a decade of growth in local popularity, Parisi fought an impossible battle to keep the show going. Pep clashed with the cable stations he hand-delivered tape to every month — the Double Helix Corporation was his primary broadcasting adversary, but he drove to southern Illinois, north St. Louis County and south-county cable stations for personal distribution. When asked what kept Pep going, Noskov says, "Ego. And the possibility of making it."

After Parisi aired a documentary episode about the end of his four-year relationship with his girlfriend Denise, St. Louis People Magazine admired World Wide as a show with "a disturbing and untamed brilliance to it, [moving] between parody and poignance." World Wide Magazine won Access America's Best of Show award. Hosted by Fred Willard, the awards show aired on Comedy Central. In 1997, an article about Parisi hit the top of the fold on the Post-Dispatch. But Pep's time was running out. His body, and the city, were failing him.

"The people of St. Louis have a very high tolerance level for being ripped off and for being made fools of," Parisi said to the camera in a 1997 segment. He'd gone down to the riverfront to cover controversial new signage on the Casino Queen, but moved steadily into a broader criticism on the decline of civilization. "The people who control the city figure you're a moron if you choose to stay here."

The people in charge "ripped all the guts out of downtown. It's sad," he laments. "They keep knocking down buildings to put up parking lots. Eventually, there will be all these parking lots, but there won't be any reason to park."

Parisi compared St. Louis to a casino. "It's a bunch of poor people getting ripped off by a bunch of rich people. That's the whole city."

St. Louis couldn't — or refused to — help Pete Parisi. It may have been the golden age of public access, but there was no funding for World Wide Magazine. Pep achieved local celebrity-artist status, knew every street and alley, had access to the most well-kept secrets, but it never translated into a living wage. "I can't afford a cellular telephone," he told a call-in show in 2001. World Wide was on a months-long hiatus. "I got no money. I couldn't work anymore." Pep's diabetes wrecked his vision. He couldn't drive a cab, so he took a part-time job as a security guard at a car dealership. "The gas, the car — I used to buy a cup of coffee every day to go to work; I can't do that anymore. I'm so poor now I don't even have money to buy insulin. I don't have enough money to buy stuff to keep my diabetes gone. I don't know what I'm going to do."

After a decade and a half covering stories such as the Kingshighway viaduct collapsing, the crack epidemic, 90 percent of Maplewood becoming used-car lots, and the factories closing in this "jerkwater town" — as he called it — Parisi was at the end of his rope. He became entirely dependent on a reportedly mutually abusive relationship with his girlfriend at the time, Linda Vaughan.

"Parisi once had a restraining order against Vaughan," D.J. Wilson reported in the Riverfront Times in 2002. On a call-in radio show, "he expressed fear of her. Vaughan dismisses such talk as 'crazy.'"

In the fall of 2001, shortly before Parisi's death, Noskov received an alarming phone message from him. "Things were getting really bad," Noskov recalls. Parisi said that Vaughan was crazy, and that he had to get out of there somehow.

On November 11, Parisi was brought by ambulance to what was then St. Alexius Hospital on South Broadway. He had entered the diabetic coma that would eventually kill him.

Noskov believes Vaughan locked Parisi in a room without food or medication, a rumor that circulated soon after Parisi's death in January 2002. Vaughan defended herself against such claims. "I'm the one who took him to get insulin," she told the RFT. "I've got the bills here. That's the most ridiculous stuff I've ever heard." After Parisi, Vaughan later married Patrick Schneider, who also says the allegations aren't credible. "[Parisi's] mind was kind of going at the end," he says. Most believe Parisi was an "overweight, insulin-dependent diabetic who loved doughnuts," and ran out of gas.

St. Louisans often experienced World Wide Magazine under hypnotic conditions: crashed out on the couch flipping channels. The show was "not appointment television, but something that I loved to stumble upon," Jim Varagona says.

Varagona was born in 1980 and became a teenager as personal cameras became affordable. Home movies took off as the popularity of Jackass and The Tom Green Show soared. Varagona aspired to create something like Michael Moore's satirical man-on-the-street show TV Nation.

"Parisi, and what he could do with the medium, fascinated me. He was a regular guy with a camera," says Varagona, "and as a teenager that was cool. It seemed like something you could do. I never thought about how he could financially pull it off."

In 1997, Varagona and some friends attended an annual World Wide Magazine cookout in Tower Grove Park where Varagona got footage of Tom Horner — "one of the wildest of the bunch" — climbing into a trash barrel and rolling down a hill. Horner had painted his face white, donned a cowboy hat and had a pacifier around his neck for the occasion. Near the end of the day, Varagona heard that the man himself wanted a word.

Pep greeted Varagona from the front seat of a sedan, insulin needle poking out of his front pocket. Varagona is diabetic, too, and in seven years would make a documentary about Pep with credit to "a diabetoboy production" underscored with a type-art needle. That day at the park, though, Parisi wanted the trash-bin footage.

Later, Varagona dropped off the tape at Parisi's apartment. Parisi greeted him dressed in boxers and an undershirt. They sat in the well-documented living room — a staple set of World Wide Magazine — and discussed editing tape, video stuff, filming strategies. The show only had a few more years left before Parisi's health failed, but Parisi had produced his own two-hour VHS compilations of World Wide Magazine titled Pussy Galore. On the cover of the tapes, he held up his cat Burtrum. The cassettes were sold at Streetside Records, but Parisi sent Varagona away with a free copy of Pussy Galore, Volume 3 — it was the inaugural piece of Varagona's World Wide Magazine archive.

"My relationship with the show was no different than any south-side hoosier," Varagona says. But when Parisi died, Varagona kept the newspaper clipping. In 2002, he was enrolled at Webster University for a media communications degree, and had decided his thesis would be the documentary P.E.P. about World Wide Magazine. Varagona began a search for footage that took him to a Hardee's parking lot, where he met a guy and paid $100 for 50 World Wide Magazine tapes bought right out of the man's trunk. The dealer was somewhat baffled and suspicious at first, wondering how Varagona found out about his secret collection ... as if being a World Wide fan linked them, somehow, telepathically. Varagona reminded the guy of his own Angelfire fan site dedicated to Parisi's work, which listed the man's contact info.

Varagona graduated from Webster in 2005. With P.E.P. completed, he found himself with a harddrive full of the best World Wide content under the sun; whole episodes and plenty of clips. Originally, Varagona hosted them on MySpace, then early Facebook, and now YouTube.

After Parisi died, the whereabouts of the big fish — the original three-quarter-inch master tapes — remained a mystery. Some suspected Linda Vaughan. Varagona worked with Parisi's mother and sister to search for them, but the boxes weren't rediscovered until 2020, when 36 of them turned up on Varagona's porch.

World Wide Magazine is a rare and complicated historical document. In a 2002 article for the Post-Dispatch, reporter Jeff Daniel argued Parisi's legacy should be preserved. "A suggestion: Put tapes of his cable-access 'World Wide Magazine' in the archives," the article read. As P.E.P. documents, the show is not a dry accounting of crime statistics and city budgets; it's a romp from the point of view of some south-city underdogs. Daniel argued that it's time to elevate the show "from controversial cult phenomenon to necessary historical document."

Varagona has been doing just that, hosting multiple World Wide Magazine YouTube channels, even before he got the masters. He is restoring the master reels — much of the film is moldy, and needs to be sent away for professional cleaning before conversion to a YouTube-friendly format, but that's what Varagona does. He's the dedicated steward of Parisi's work.

Many of the themes and sentiments of this archive are not pretty. There's overt racism, homophobia, xenophobia, sexism — it's all over the archive and inexcusable.

Unfortunately, those sentiments were (and are) widely held in popular consciousness. As Don Wayne (a.k.a. Black Jesus) points out in a recent interview, north St. Louis is in just as bad condition as it was in the World Wide Magazine heyday. The north side is still segregated, falling apart and neglected. It is largely excluded from the urban renewal happening south of Delmar. "Why don't white and Black folks come together to fix north St. Louis?" Wayne asks. It's the same question in 2022 as it was in 1987.

Questions around Parisi's death are largely over. What we're left with is his legacy in Varagona's basement. A historical archive doesn't have to be dusty — it is whatever we say it is, and can include Pete Parisi filming a charity car wash run by hot ladies in bikinis, or a lunchtime trip to an all-you-can-eat buffet, or Vanessa "The Songbird" performing below the Bevo windmill.

As Varagona puts it, World Wide Magazine is St. Louis' home movies: awkward, cringeworthy, sometimes terrible, sometimes sublime. As Daniel wrote in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch: "Maybe it's time for the reject to be accepted. Time for the terminally unhappy Parisi to have something to smile about."

This story has been updated to reflect the correct size of the master tapes. We sincerely regret the error.