The road to the Southeastern Correctional Center passes alongside a verdant field of corn. The stalks rustle in the afternoon wind, as if stretching toward the August sun. Peeking above the leaves, the brutalist gray face of the prison's intake center greets visitors entering the sprawling compound. For Tim Prosser, it is both home and coffin.

Tim's life began falling apart long before he moved into a trailer in Ste. Genevieve. It started, he says, when he lifted a piano in 1988.

"It was just a regular household move," Tim recalls, resting his meaty forearms on a table in the prison's visitation room. "I moved furniture for 21 years, and I lifted a piano, done it a thousand times, if not more. I turned wrong. I have no idea what happened. It sent a sudden pain down my back and my legs."

Tim kept working, but the pain began to overtake his life. Doctors told him he had a couple herniated discs in his lower back. They gave him pills, starting with Vicodin and moving on to Darvocet and Percocet. The prescription drugs dulled the pain — along with everything else.

In the early '90s, several Prosser families migrated south to Ste. Genevieve. Tim followed, but he says memories of those years are blurred by the pills. He worked odd jobs to make a living, repairing cars and menial labor, whatever his broken-down body could handle. In 1997, he suffered a serious car accident, and the ensuing medical costs wiped out whatever savings he had left. He moved in with his parents.

It was around 2000 when Tim, having recovered from the car accident, was offered meth by an acquaintance in a billiards league.

At first, it felt like a miracle cure.

"It gave me function," Tim says. "There was no pain and I could move. I could get up every day."

But in just three short years, Tim's meth addiction had derailed his life. He found himself in the crosshairs of the Ste. Genevieve police and local drug task force.

Tim hadn't been a perfect citizen. Years before succumbing to meth, he pleaded guilty in 1988 to unlawful use of a firearm, and he had enough of a drinking problem that he racked up three DWI convictions over the ensuing decade. But those crimes, all misdemeanors, resulted in nothing more than probation.

In 2003, seemingly overnight, Tim became a cautionary tale, the modern-day version of the severed head placed outside castle walls. His life sentence was heralded as a warning to other drug dealers.

"The people of Ste. Genevieve County have spoken," a representative for the Ste. Genevieve sheriff told a local paper after Tim's sentencing. "If you're making, buying or selling illegal drugs in this county...it will not be tolerated."

But there are reasons to be skeptical that Tim was anything other than a small-time meth cook primarily interested in feeding his own addiction.

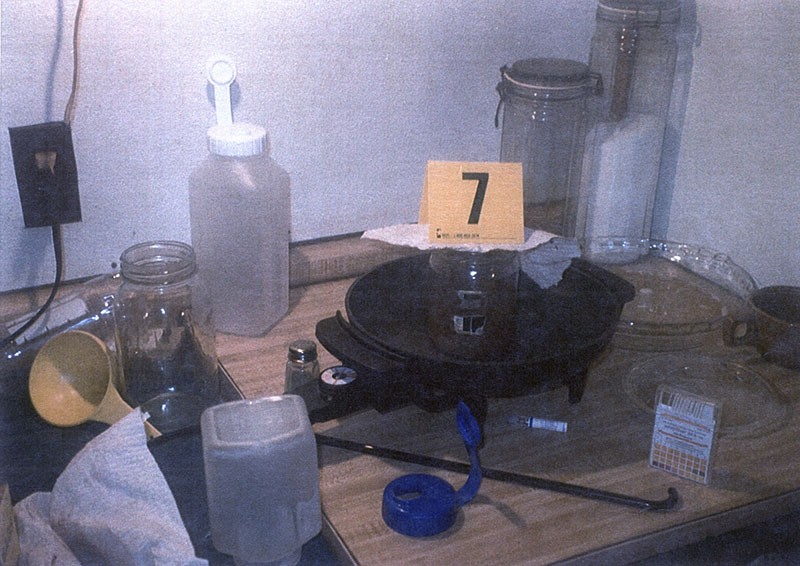

First, Tim didn't actually possess 350 grams of meth. Officers didn't find plastic bags bulging with powder or crystals; instead, they filled evidence jars with the liquid bubbling in various containers found around the trailer. That's what tested positive for containing methamphetamine.

However, liquid in the process of being distilled into meth isn't equivalent to the stuff you sell on the street.

"That's another bizarre aspect of the statute," says Kinsky. "Ninety grams of pure meth is worth a lot. Ninety grams of a liquid that contains meth is, I don't know what it could produce typically, but it's not the final product. It's not going to produce anywhere near 90 grams of pure meth."

In fact, Tim claims the 350 grams of liquid would have yielded just three to five grams of usable meth — and even that small amount would have been divided between other users who contributed ingredients.

And if Tim really was running a "large-scale" operation, where was the money? Officers found a wad of $3,000 cash in Tim's pocket, but court records show that Kinsky ultimately ordered the money returned after Tim's family proved the cash had come from a social security settlement check. Even the informants working for law enforcement, too, had offered him ingredients, not cash.

The totality of the evidence backs Tim's contention that he was an addict, not a kingpin. His history of chronic pain preceding prescription drug abuse follows a similar trajectory to the tens of thousands of Americans trapped in the opioid epidemic sweeping the country. Although the epidemic has gained media coverage more recently over its link to heroin overdoses, differences in regional drug markets mean that rural towns like Ste. Genevieve have been flush with a different painkilling alternative.

At the time of Tim's sentence, meth was decimating rural communities. Law enforcement was eager to show they were taking it seriously. But that meant, in many cases, toughening up drug laws to lock up addicts after the fact.

Tim is still in pain, a sensation he compares to being endlessly whacked about the limbs by former Cardinals slugger Mark McGwire. These days, prison doctors have put him on a nerve-dampening medication called Neurontin. It still doesn't do much.

As years passed, Tim settled into prison life. He kept himself out of trouble, receiving just three conduct violations since 2004. He lives in the honor dorm of the Southeast Correctional Center.

Six years ago, Tim joined a program that allows inmates to train shelter dogs deemed unwanted and unadoptable. The program is called Puppies for Parole. So far, Tim has taught some 30 dogs basic obedience skills and socialization. Eventually, the dogs are sent home to new adoptive families.

Tim stays.