Jennifer Anderson had only recently landed a gig at the Golden Eagle Saloon in Belleville when her boyfriend broke her heart and moved to Florida. But it didn't take long for the strong-willed young bartender with the wide-set brown eyes to catch the attention of 61-year-old Thomas Venezia, a down-on-his-luck ex-con who was lending a hand at the neighborhood tavern.

The past seven years had not been kind to Venezia. The man federal prosecutors claimed once helmed a $48 million gambling empire now lived in a dilapidated house at 311 Mascoutah Avenue, next door to the Golden Eagle.

His pauper status must have grated on Venezia, who in the mid-1990s boasted a weekly income of $16,000 and a payroll that included politicians, chiefs of police and a small army of strippers, bouncers, route men and tavern owners — spokes in the wheel of his criminal enterprise. In the words of one Washington Park police officer, "Venezia did run the city of Washington Park."

Or he did until 1995, when federal prosecutors unveiled a ten-count racketeering indictment that eventually ensnared the Venezia family, area businessmen and Washington Park Mayor Sylvester Jackson. The imbroglio also spawned the federal conspiracy trial of Venezia's attorney, Amiel Cueto, which reverberated 850 miles away in the nation's capital when prosecutors named Jerry Costello, a Democratic Congressman from Belleville, an "un-indicted co-conspirator."

Tried, convicted and sentenced to fifteen years in prison, Venezia served seven years and returned to Belleville in 2002 a changed man. The mogul who'd once spent his mornings gliding from tavern to tavern in the air-conditioned comfort of a Lexus sedan now drove a car on loan from his friend Robert Staack, who ran the Golden Eagle. Gone was the midnight glamour of Cheeks, Main Street and Club Exposed, the topless nightclubs the feds seized from Venezia. In their place were a diagnosis of throat cancer, a "consulting" gig with his buddy Staack and a monthly income of $387.

But there was one thing the government couldn't take away from Tom Venezia: his charm. It was Venezia's fabled charisma that wowed the power brokers of southern Illinois, and it was that same magnetism that wooed Jennifer Anderson, a 2002 grad of Belleville East high school who was now dabbling in the area's seamy underworld.

Born the third child of four to a working-class family, Anderson was athletic and outgoing, with a soft spot for life's underdogs. She had straight brown hair, an enigmatic smile and a well-toned physique. She also had a wild side. The girl who'd been nicknamed "Froggy" by her fast-pitch softball team in junior high (for her prowess at catching flies) was a knockout at 21 and quickly became a favorite at the Golden Eagle. Within months of signing on in late 2004, she was living next door with Tom Venezia and managing the bar, which one co-worker describes as "the Coyote Ugly of Belleville."

The wiry-haired Venezia, on the other hand, had never cut the figure of the stereotypical mob don. At the height of his power he'd favored tailored suits, driven luxury cars and was never without a fat roll of cash. But he stood five-foot-seven. A thick bush of a mustache punctuated his elongated face, and watery brown eyes were framed in oversize glasses.

"He could somehow make her feel important. He knew what carrots to put in front of her," says Jennifer's father, Michael Anderson, who still puzzles over his daughter's attraction to a man 40 years her senior. He adds that Jennifer told him and his wife, Cynthia, that Venezia had promised to give her the Golden Eagle. "She had us snowed."

But the Andersons could hardly have imagined how their daughter's relationship with Tom Venezia would end. A few hours after midnight on the morning of July 19, police say, Venezia shot Anderson and then turned the gun on himself.

Jennifer Anderson was shot execution-style, with a single .38 caliber bullet to the base of her skull. Venezia's death was more gruesome: He was discovered seated in a bedroom recliner, dead from one pointblank shot to the temple, the bullet lodged in a nearby door.

Toxicology reports would reveal traces of alcohol in Anderson's system, while Venezia had been legally drunk. Police promptly ruled the deaths a murder-suicide and closed the case. Statistically, Anderson became Belleville's seventh murder in a year during which residents have seen their small town morph into a mini-murderopolis — as of this writing, twelve violent deaths and counting.

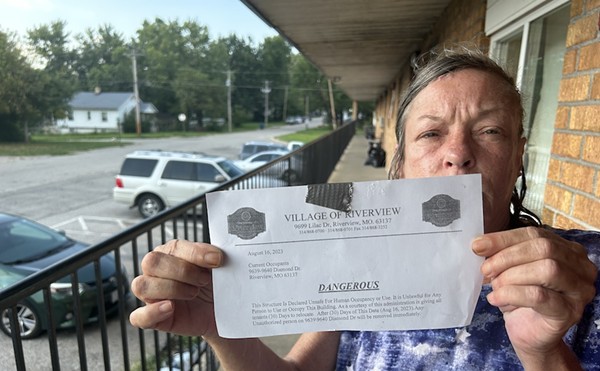

But despite the official version of events, three months after the killings the Andersons remain unconvinced. They want to know why Venezia was living in a house that, according to Belleville records, did not have a current occupancy permit. They want to know how a convicted felon came by a .38 caliber Smith & Wesson handgun. And they want to know more about what happened in the wee hours of July 19: How could Venezia, his 61-year-old body withered by cancer to about 100 pounds, have wrestled their athletic, vibrant daughter to the ground and shot her?

"Do I believe that Tom could have shot Jennifer? Yes. Everything points to a desperate man losing everything he had, and why not take the coward's way out?" Michael Anderson reasons. "At the same time, when you look at the property records and talk to the people involved, there is a whole lot of mystery.

"There's definitely been a murder. But who shot Jennifer and who shot Tom remains to be seen."

When the criminal history of late-twentieth-century southern Illinois is written, Thomas Venezia will tower over the region's motley collection of grifters and petty thieves. A St. Louis boy with an eighth-grade education, Venezia crossed the river in the late 1980s and bought a Washington Park strip club, the first of his three topless bars. He soon beefed up his portfolio, purchasing two vending companies to form Ace Music/B&H Vending, the economic engine that would deliver his fortune.

A supplier of coin-operated pool tables and cigarette machines, B&H also dealt in bar-top video-poker and -slot machines. But these weren't factory-fresh machines. Venezia took games like Magical Tonic, Robo Pit Pong and Cherry Master 91 that were manufactured to be operated "For Amusement Only" and rigged them to tally accumulated "credits" so winning customers could be reimbursed in cash from a till maintained by the barkeep. While they were at it, B&H workers also modified the machines to accept dollar bills — a lucrative innovation.

Venezia ran a full-service shop. Naturally, B&H supplied and repaired the machines free of charge. If a tavern's till ran dry, a call to B&H was all it took for a "route man" to arrive with a fresh monetary infusion. Gambling profits were split 50-50 between B&H and the tavern owner, whereupon all receipts were destroyed.

To insulate his business, Venezia placed family members in key positions. His wife, Sandra Nations Venezia, ran the "money room," a vaultlike chamber where gambling proceeds were commingled with the company's legitimate earnings. A son, Milan Venezia, worked as a route man before taking over management of his father's strip clubs.

But as Venezia's empire expanded, he needed more protection from nosy law-enforcement agencies. To this end, he enlisted the aid of Amiel Cueto — pronounced kwee-toe — a powerful Belleville attorney who Venezia once boasted "owned" fifteen of the seventeen judges in St. Clair County.

"I was told that if anybody was arrested that [B&H Vending] would make immediate bail for the people that were arrested. After they were released...the owner of the tavern...would be charged [with] a misdemeanor, fined $1,000 and [B&H] would take care of the fine, the bail — everything," Belleville tavern owner Dennis Dehn would testify during Venezia's 1995 racketeering trial. "[T]he machines — or machines that were confiscated — new ones would be back in the next day."

Venezia rounded out his operation by recruiting Sylvester Jackson.

A low-level Democratic operative, Jackson was elected mayor of Washington Park in 1989, the year Venezia bought B&H Vending. Jackson would later testify that his first business meeting with his future boss took place at a Washington Park topless club. "He wanted to expand the vending business, the gambling," Jackson, who turned state's witness, told jurors at Venezia's trial.

Venezia proposed that the mayor come to work for B&H Vending. To Jackson, whose mayoral duties earned him the princely sum of $400 a month, the arrangement sounded attractive, but he expressed concern that being on Venezia's payroll might compromise his official duties.

"Tom at that time said he was going to check it out for me," Jackson testified. "A few days later Tom got back with me and told me he talked to Ame [Amiel Cueto, Venezia's attorney] and Ame said it wouldn't be a conflict."

(Cueto says Jackson perjured himself during Venezia's trial. Jackson could not be reached to comment for this story.)

His conscience clear, Jackson assumed duties as a "trouble shooter" for B&H, and Venezia put him on the payroll at $500 per month. In addition, Jackson told jurors, each week the boss would slip him an envelope containing $500 cash.

Jackson, who is African American, told jurors that Venezia wanted him to get B&H machines installed at "black stops." The aspiring racketeer also counted on the mayor to keep local police at bay.

Conveniently, the latter role was a logical extension of Jackson's mayoral duties. "[T]he topless business in Washington Park was one of our main resources," he would testify. "We didn't want the police department [coming] into the topless-club business where the vending machines was at, because I didn't feel it was right for police officers to be around that type of atmosphere."

As Jackson's relationship with Venezia deepened, the under-the-table envelope got fatter. By 1994 the mayor was collecting $2,000 a week in cash. His portrait hung in B&H's Belleville lobby. Venezia also loaned him $25,000 to remodel a lounge Jackson's brother owned. The loan, like all the others Venezia made to local tavern owners, was repaid over time via a deduction from the tavern's share of the gambling loot.

There were favors on Jackson's end, too. "When Tom and I got a little bit more acquainted, and I understood a little bit more about the business...[I made] Sandy Nations [a] deputy marshal of the Village of Washington Park," Jackson told jurors. "A few months later...[Venezia] come up with a list of other guys...that he wanted commissions for."

Though Sandra Nations, Milan Venezia and several other Venezia employees had no law-enforcement training, their badges entitled them to carry firearms and insulated them from police scrutiny.

At Venezia's request, Jackson also appointed a private investigator named Robert Romanik police chief of Washington Park.

Venezia would later describe his relationship with Jackson as "a marriage made in heaven."

Conceded Jackson: "Going to work for B&H Vending meant I couldn't really perform my duties when it came to enforcing the law on certain things. I closed my eyes."

Soon after taking office in 1989, Sylvester Jackson met with George Sirtak, a local businessman in need of a liquor license. Sirtak aimed to open Club Hollywood — which would be the fourth strip club in Washington Park (population 5,000).

Sirtak would later testify that their first meeting went well; Jackson said acquiring a liquor license would be a snap. But plans hit a snag when the St. Clair County Zoning Commission told Sirtak he'd need a special zoning permit to serve alcohol.

When Sirtak and the mayor next met, Jackson assured him zoning was a non-issue. "[He said] they had decided to get their own proceeding to zone for Washington Park," Sirtak told jurors during Venezia's trial. "[He told me] to go back up to St. Clair County and get a permit for a restaurant. By the time I was done with the building...the zoning would be there from Washington Park."

Sirtak had no reason to distrust the pro-business mayor. Tom Venezia, whom Sirtak knew as the owner of the Main Street strip club, had a good relationship with Jackson. And why not? The clubs brought in revenue for the city. So Sirtak broke ground on his new club and obtained a restaurant permit, taking out a $280,000 loan and emptying his savings account.

"When things were getting close to completion, I made a call to Mayor Jackson," Sirtak testified. "I had asked him if the zoning problem was taken care of. He said: 'Don't worry about that. Come get your [liquor] license and open up.'"

The club opened in November 1989 — only to be shuttered three and a half weeks later by the St. Clair County Sheriff's Department for operating without a proper zoning permit.

Jackson had failed to deliver on his promise.

For the next two months, the club remained closed while Sirtak scrambled for a permit. Jackson and Tom Venezia counseled patience. But bills were coming due, and Sirtak was growing increasingly anxious.

Sirtak told Venezia and Jackson he wanted to reopen as a topless venue that served only soda. But they counseled against the idea, warning that the club "would bring the state down on us."

Sirtak did it anyway. "[The] night that I opened, the chief of police, Bob Romanik, came in and took the license with him and closed the club down," Sirtak testified. "[Jackson] stated that at that point in time it would be impossible for me to ever acquire a liquor license in Washington Park, that I was not the right guy."

In a subsequent meeting with Jackson and Venezia, the mayor suggested Sirtak consider selling the club — to Venezia.

"I mentioned $350,000," Sirtak recounted in court. "[Venezia] laughed, shook my hand and said: 'Good luck: You don't even have a liquor license.'"

Two months later, facing mounting debt and zero income, Sirtak called Venezia.

"He asked me how much I had in the property," Sirtak told jurors. "He said, 'I would be interested in giving you $300,000.' I said that would be fine."

Venezia bought Club Hollywood, renamed it Cheeks and opened with all permits in place.

A year after George Sirtak was relieved of Club Hollywood, East St. Louis found itself surrendering its city hall.

A man named Walter DeBow, who'd been severely beaten while spending a night in jail on traffic violations, had sued the city. But when the wheelchair-bound and brain-damaged plaintiff won a $3.4 million judgment, the debt-ridden municipality couldn't come up with the cash. In lieu of payment, a federal judge awarded DeBow the deed to the East St. Louis City Hall and 220 acres of riverfront property.

Within weeks of acquiring the deeds, DeBow sold the properties to a secret land trust.

Enter Tom Venezia, Amiel Cueto and their joint enterprise, the Illinois Port and Harbor Authority, which aimed to return city hall to its rightful owner — in exchange for exclusive riverfront development rights.

"The land trust had agreed to sell Illinois Port and Harbor the deed and title to the East St. Louis City Hall, plus 220 acres of city-owned land...for $1.2 million," Venezia told jurors when he was briefly transferred from prison to testify for the prosecution at Cueto's 1997 conspiracy trial. "In turn, Illinois Port and Harbor was to give all that up to the City of East St. Louis for exclusive development rights [of the riverfront]."

The deal met with stiff public opposition and was soon tabled. But the effort taught Venezia that his gambling proceeds could be leveraged into a legitimate business. From 1992 to 1995 he was involved in several property deals with Cueto and another investor, Richard Bechtoldt.

In one such deal, the trio formed a company called DeKalb Crab Orchard, which aimed to develop casinos on Native American land. The investors formed yet another company, ILLART (ILL for Illinois; ART for Amiel, Richard and Tom), whose purpose was to acquire an interest in the DeKalb deal and similar arrangements statewide. According to Venezia's subsequent testimony, Cueto maintained 50 percent of ILLART, while Venezia and Bechtoldt each owned 25 percent.

"[Cueto] would retain 50 percent," Venezia testified. "In the event that [U.S. Representative] Jerry [Costello] didn't run for [re-election, he'd] have Jerry Costello as a partner."

Meanwhile, the investors continued to eye the East St. Louis riverfront. Property records indicate that in 1994 they took out a $600,000 loan to purchase 32 acres of riverfront property via a company called En Futuro.

"The division was going to be 50 percent [for] Amiel Cueto, 25 percent for...Richard Bechtoldt and 25 percent for my nominee," Venezia testified. Asked by prosecutors why Cueto was to get 50 percent, Venezia stated, "It had something to do with [U.S. Representative] Jerry Costello, that he would be his partner if he didn't stay in Congress, or something to that effect."

When he took the stand in Cueto's trial, Bechtoldt backed up Venezia's version: "I was told that Jerry Costello was a silent partner." When the U.S. Attorney asked Bechtoldt whether he'd been told of Costello's involvement by Amiel Cueto, Bechtoldt replied: "Yes."

Congressman Costello has consistently denied any involvement in any land deals with Venezia.

"Costello didn't know anything about that," seconds Cueto, a childhood friend of the congressman, once known for his sizable contributions to the Democratic Party. "None of it ever made a nickel. There was never really so much as a spade of earth turned on anything. None of these projects were advanced past the planning stages. There was a lot of paperwork done and documents signed, but it turned out to be nothing, and I don't think it ever had a chance to be anything but nothing."

Though he kept a low profile before settling in Belleville, Thomas Venezia's name had percolated into public consciousness in 1962. It was in December of that year that Venezia, then age nineteen, shot and killed an ex-convict named Elmer Dowell with a .38 caliber pistol.

According to an article published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, the circuit attorney ruled that the killing, which took place at a midtown tavern owned by Venezia's father, was committed in self-defense.

Two years later St. Louis police again booked Venezia on a murder charge — this time for the New Year's Eve slaying of John Johnson, who was shot in the head at the Pink Elephant Lounge on the 3800 block of Olive Street and then dragged outside. Venezia denied any knowledge of the slaying; the charges were subsequently dropped.

Suicide, too, played a role in Venezia's life: He told several associates that his father had killed himself.

Still, those who knew the racketeer after his release from prison find it hard to imagine that Venezia could have shot Jennifer Anderson, only to turn the gun on himself.

"I am 100 percent convinced that he did not kill her and then kill himself," says a bartender who worked with Venezia and Anderson at the Golden Eagle. "He was too proud; he would not have took her with him."

The bartender, who declined to be identified in this story for fear of reprisal, stresses Venezia's reputation as a stand-up guy: "One night [my sister and I] were drunk, so we called a cab and left her car at the bar. Well, she come back the next day to get it and someone had slashed both her driver's-side tires. You know what Tom did? He called a tow truck and had them come get her car and then had tires put on her car. He didn't want anything for it. It was just his way of helping his girls out."

By "girls" the bartender means the women who worked with Venezia at the Golden Eagle, a neighborhood bar whose most noteworthy features were its exposed brick, small patio and hot young barmaids.

But the Golden Eagle's tidy appearance belied the wild nights Venezia hosted there.

"Weekend nights were unreal. If you were drunk and dancing on top of the bar, that was fine," says Pat Williams, who worked with Venezia for a month in early 2005. "I wouldn't say that he would encourage the girls to dance on the bar, but if you were up there he'd be right out there along with the rest of the crowd, rooting you on. You definitely would not be disciplined for it. If a customer bought you a shot, you were expected to take it."

For the girls behind the bar, Williams says, Venezia expected a dress code worthy of his glory days: "Very short shorts with the ass cheeks hanging out, low-cut tops and high heels." Another bartender who quit after a few days at the Golden Eagle calls the bar "sleazy."

The Golden Eagle was certainly a step down from the flesh factories Venezia had once called his own. But seven years in prison had diminished the man. And when Jennifer Anderson entered his life, she must have reminded the fallen racketeer of the life he'd once led. Anderson was mildly dyslexic and kept copious diaries to articulate her thoughts. She also carried a pocket dictionary she'd refer to when words escaped her. Family members and friends say she had a penchant for collecting orphaned animals. But it was her party-girl streak that endeared her to men — and ignited jealousy in their girlfriends.

"Girls [would] come into the bar with their boyfriends, and as bartenders we've got to sell our liquor," says a co-worker who asked not to be identified in this story. "It's not that we'd do anything to their boyfriends, but their boyfriends would look at us and they'd get pissed off. [Some of the girls] thought she was a whore. One night we were at a party after work, and they all tried to gang up on her. But Jennifer was never a whore or a skank. They were jealous: The girls didn't like her because she was pretty."

But Venezia did like her. Though she had no experience running a tavern, within months of signing on she was managing the Golden Eagle and living next door with the former mob boss. But she kept quiet about the relationship, and to this day friends and family are uncertain whether they were romantically involved. Occasionally she'd leave a party to help Venezia with something; she ferried him to his chemotherapy sessions and drove him around. But friends say she rarely talked about him. Her parents say that before she died she'd begun dating someone new. In the weeks before his death, neighbors report having seen Venezia out walking, riding his bike and even jogging. After the killings Milan Venezia told reporters his father's cancer was in remission.

Anderson's parents say she never told them she was living with Venezia.

"I was very concerned but constantly lied to by her," maintains Michael Anderson, Jennifer's father. "She'd tell me that she'd just leave the car [at the bar] and sleep at a friend's house."

When the Golden Eagle was shut down in the spring of this year for serving underage drinkers, Anderson got a job stripping at the Penthouse Club in Sauget, where she worked under the stage name "Raven." By all accounts she wasn't happy with the job.

"She wasn't liking all of the clientele," says longtime friend and onetime boyfriend Jared Sileven. "She was going to quit stripping and go back to the bar business."

The Andersons, who live only a few blocks away from the tavern on Mascoutah, say they hadn't known about the strip-joint job. "We didn't know she was stripping until the day she was found," says Michael Anderson, who works as a home rehabber.

Still, the Andersons suspected that their daughter, whom they describe as fearless, trusting and loyal, was mired in a bad situation. "From the moment she took a job at the Golden Eagle there was a decline," Michael Anderson says. "When it comes to these people [like Venezia], anybody's daughter is in trouble. This innocent little kid became a party animal."

Part 2: Thomas Venezia takes a new wife, as his east-side empire crumbles.