I want you to look at the whole economic system as one enormous tit," Lyman Felt, the lusty, ferociously articulate and unreformed bigamist at the heart of Arthur Miller's The Ride Down Mount Morgan, tells his nurse in the play's opening lines. "So the job of the individual is to get a good place in line for a suck."

Most men have appetites. But Lyman Felt has something infinitely more rare. The man has hunger – hunger for risk, hunger for wealth, hunger for love and literature. Hell, this guy even waxes poetic about life insurance. But mainly? Lyman hungers for women – the cause of his greatest joy and ultimate undoing. He is a libertine hounded by the wolves of his own mortality, and though his unapologetic pursuit of earthly delights ends in tabloid scandal and the ruin of both marriages, Lyman, broken and alone, wouldn't trade his past pleasures to avoid his current pain.

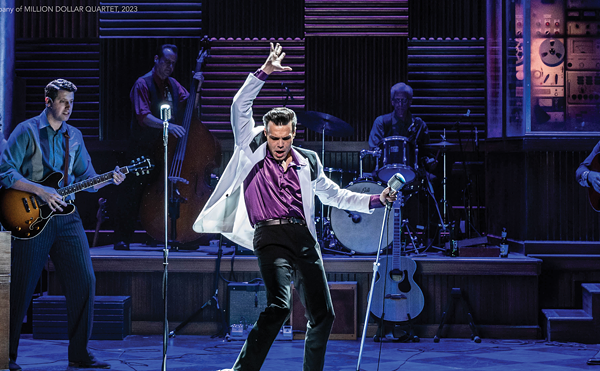

Like so many of Miller's plays, Mount Morgan, which St. Louis Actors' Studio opened last Friday at Gaslight Theater, brings morality throbbing to life – namely, what does it mean to be faithful? And what's so wrong with bigamy, come to think of it? These questions crowd onto the stage as this middleweight drama opens in a hospital room where Lyman is recovering from a car crash. His skeleton smashed, Lyman first believes it's only a dream, but reality sets in soon enough: Both Theodora, his proper Manhattan wife of several decades, and Leah, his carnal, upstate bride of a more recent vintage, have both arrived at the hospital. They meet in the waiting room, and, well, we're off the starter blocks, embarking on an episodic journey that melds past, present, nightmare and fantasy into roiling polemic on the nature of fidelity, truth, and societal constraint.

Miller gives Lyman (John Pierson) the bully pulpit, as the insurance executive challenges a dismayed Theodora (Amy Loui) to explain "how this worthless, loveless, treacherous clam could have single-handedly made two such different women happier than they'd been in their lives." He does feel pangs of remorse. He regrets, for instance, not divorcing Theo when he decided to marry Leah (Julie Layton), and Lyman suffers a jarring, feverish dream where his two wives – remade in the key of Stepford while clutching a pair of gleaming chef's knives – agree to share him. But as for following his heart, keeping two families, and raising a middle finger to convention – no matter the price? Well... "I may be a bastard, but I am not a hypocrite."

Inhabiting a lusty muscularity, Pierson speaks extravagantly as he bounds about the clever four-tiered stage (designed by Cristie Johnson), joining the poetry of others (Joyce, etc.) to his own doggerel ("her pink cathedral") as he pleads his case for big love. The play slips quickly between past and present, and director Bobby Miller intermittently dovetails multiple scenes in a masterfully interwoven line dance. As Theo, Loui is a convincing study in icy Upper East Side entitlement – a strong counterpoint to Layton's terrific Leah, the brassily sensual working girl. Both actresses deliver strong performances, but their characters are limited. They are clearly the product of a man's imagination and lack much depth outside their relation to the brooding and fatuous Lyman. Instead of mounting a serviceable argument against his self-justifying torrent of words, they simply lash him with guilt and hurt feelings.

All this means that although Lyman wins the argument, he loses the day. Societal convention inevitably wins out, and the wealthy executive must endure the minor tragedy of divorce. (What? It could've been worse...) Regretful but unapologetic, Lyman hasn't lost everything. He'll soon be hungry for more, and that gives the play a smallish, unsatisfying feel that leaves the audience entertained, if a bit peckish.

![[INSERT CATCH PHRASE HERE, BABY]](https://media1.riverfronttimes.com/riverfronttimes/imager//u/4x3-s/2505303/9505509.0.jpg?cb=1643065092)