Former Post-Dispatch Columnist Sylvester Brown Is Content at Last

Sylvester Brown Jr. remembers the first day he walked into the brick, box-shaped building on North Tucker Avenue. It towered over the street, proudly proclaiming the words “St. Louis Post-Dispatch” in black lettering. Brown can still see the marble wall that greeted him as he opened the doors. He can still see the Joseph Pulitzer quote displayed on it. The memory brings a soft smile to Brown’s face. The good old days.

In 2002, Brown was hired as a metro columnist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Twenty-five years before, Brown didn’t even read or write on a regular basis. In fact, he had dropped out of high school. He had attended community college, with the intention of studying art and becoming a cartoonist. He had started a makeshift magazine so he could practice his newfound interest in writing. Hell, if it weren’t for The Autobiography of Malcolm X, a text he read in community college, and the first he had ever encountered with a black protagonist, who knows where he would have ended up.

When Brown was a boy, with his father in and out of the picture, his mom working multiple jobs, and the house packed with eleven kids, Brown would wander around St. Louis, daydreaming. “I saw myself driving the nice cars, being on the billboards, having all of those nice products. Dreaming was my way out, my escape,” Brown says. And now he had escaped. Sylvester Brown was at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

“This is cool,” Brown remembers thinking when he walked through the front doors. “I am a part of real legitimate media.

“But it was only cool for a moment.”

Ten years after he left the P-D, Brown, 62, is in his second-floor apartment in Old North. Despite the 60-degree day, the street is empty, and the block has its fair share of the green grass of vacant lots. The front of the apartment building is painted a warm blue. On one of the three steps leading up to the building is the word “smile.”

The display was painted by a local artist, Jamaica Ray, who lives in the same apartment complex. The color livens the block. It is also Brown’s way of putting his money where his mouth is. He believes in “do-for-self” economics, a concept that emphasizes maintaining a community without the help of outside sources. He shares the idea with the kids at his Sweet Potato Project. Brown created the project in 2012, helping local students use local vacant lots to grow their own sweet potatoes in the summer. They then use them to bake cookies, which they sell to buyers in the fall and winter. He regularly draws 50 applicants for each year’s twenty spots.

But the sad reality is that if it weren’t for his time and his fallout with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the Sweet Potato Project may never have come to fruition.

For fifteen years before Brown came to the daily, he developed what he calls a homegrown “African-American investigative magazine,” Take Five Magazine, with the help of his then-wife and their friend Jabari Asim. But when their minimal revenue stream forced them out of business, Brown got a call from the Post-Dispatch. They were looking for someone different than longtime black columnist Gregory Freeman.

Without traditional journalism experience, Brown couldn’t believe he was qualified. “As it turns it out, they were looking for someone who wasn’t like Greg. Greg was very affable, people liked him, he was a middle-of-the-road guy. But they told me they wanted someone who was going to dig and explore the whole race issue,” Brown says.

This was the “cool” phase. The Post-Dispatch provided him with space to share his thoughts. Readers were attracted to his argumentative and thought-provoking style. “The most important thing that people said to me was, ‘I didn’t always agree from you, but I learned from you,’” Brown says. He secured a house in south St. Louis. He enrolled his two daughters through private school. He bought cars for both himself and his wife.

Then, in 2005, Iowa-based Lee Enterprises bought the Post-Dispatch, and the good times came to an end.

“It seemed to me that their shift was less controversy. Less confrontation. Less conflict. Let’s just be nice,” Brown says. “I was on the mayor’s ass. They would bend over backwards to accommodate him. To the point they were trying to send my columns to him for approval first. That’s not journalism.” Brown specifically remembers the paper trying “appease those red-state readers” in the county.

Brown came home disgruntled, exhausted from all of the tension. “It was like torture. I felt like a boy...My stomach would hurt. I felt compromised. I felt less than.”

Brown chafed at the direction from the paper’s new owners. “It became clear that I wasn’t that Negro. I wasn’t the guy that was going to smile and be happy to be there...The management had no respect for not only the black readers, but for black employees. That really started to eat me up inside.”

But Brown stuck with it. "I got national recognition,” he says. “At the Post-Dispatch I realized how journalism can change events.” He remembers writing about a woman who needed a kidney. It wasn’t much longer before she received one. "I recognized the power of working for a major newspaper.”

Brown toughed it out until 2009, when he wrote a story about a group of East St. Louis ministers and their trip to Washington, D.C. Brown covered the leaders’ effort to garner funds from D.C. lawmakers for their sustainable energy project. He says he was in D.C. for another press conference at the time of the ministers’ trip, working on a book project.

But when another Post-Dispatch staff member saw him, that person phoned their boss. When Brown arrived at the office the next day, they told him to pack his stuff. He had violated the newspaper’s ethics policy, they claimed. The newspaper believed that the ministers had compensated Brown for writing the story on them, which Brown insists to this day was not the case.

“This [trip] was for my own edification, my own project,” he says. “It had nothing to do with the Post-Dispatch. If I came home with a glowing column about what they were doing in D.C., then they had me dead to rights. It would have been a conflict of interest. But I didn’t. I was writing about something totally different.”

Asked about Brown’s time at the P-D and his departure, the newspaper’s spokeswoman, Tracy Rouch, refers the RFT to a “note to readers” published April 14, 2009, which she says still summarizes its stance.

It reads: “Sylvester Brown Jr. is no longer writing a column for the Post-Dispatch. Brown accepted the offer of a free trip to Washington from supporters of a group that he had written about in a column the day before. The column, ‘Metro East leaders head to D.C. to tout E-Macrosystem,’ ran on March 26. Brown also had not notified his editors of his trip or the offer. Our integrity and our credibility with readers is of utmost importance to us. Our ethics policy clearly states the parameters regarding conflict of interest, and what our journalists can and cannot do.

“Brown declined an opportunity to write a farewell column.”

Brown says the newspaper offered to keep quiet about the situation. Brown thought about it, but decided he didn’t want to go out that way. Instead, he called a press conference, announcing his resignation. “I think I walked out with my head up. I felt liberated,” Brown remembers.

Brown landed on his feet, working with national talk show host Tavis Smiley at his publishing company. But the job was on and off and money was scarce again. Brown’s wife worried. “You need to get yourself another real job,” he says she told him. A year after he left the paper, they separated.

Two years after that, he lost the house. “Everything was gone...it was like ground zero for me,” Brown remembers. “There were times when I was like, ‘Sylvester, you really screwed up, you set yourself back.’”

It wasn’t much longer before Brown returned to his old stomping grounds of north St. Louis, the same neighborhood where he used to wander and daydream, the same streets where he says his father was beaten by police officers. Through Smiley, he met “prominent black thinkers” like Louis Farrakhan, Al Sharpton, Cornel West and Eric Michael Dyson. Brown’s interactions with them made him realize that he wanted to help kids in his community.

He learned about Barack Obama’s Healthy Food Financing Initiative, which brought more nutritious food options to disadvantaged areas. That’s when the idea for The Sweet Potato Project popped into his head. He had never grown anything before, but he knew sweet potatoes were tasty and easy to grow. Why not let the kids grow and sell these healthy vegetables?

Ever since he read The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Brown has been interested in “do-for-self” economics. Now he had a chance to implement it. Through the Healthy Food Financing Initiative, he could get the funding to teach these kids valuable skills about agriculture and business. All they would need were vacant lots, a space to grow. And north city has that in volume.

“I want kids to wake up knowing that the food from their mother’s garden is at the grocery store, at the gas station. That we can go to the grocery store and have our own label like Del Monte or Glory foods. It’s those little things that will solidify the idea that we can control our own destinies,” Brown says.

He began the program in 2012, raising money himself. (The project is not a registered nonprofit, but can accept donations through the North Area Community Development Corporation.) The ten-week program starts in the summer; students spend four days a week with Brown. It’s during this time that they start planting the sweet potatoes, circling back in the fall and winter to sell the cookies.

The program became so popular that he had to start an application process. Brown looked for students not with the best grades or cleanest disciplinary record, but those who truly wanted to engage with their community. That’s because the students aren’t simply growing plants and shipping them. They’re writing, reading, talking and analyzing the world around them.

Brown has students bring newspaper clippings to class, where they share and discuss their findings. He also takes them on “neighborhood walks,” where they write about what they see. They even travel outside of north city to places like the Central West End. He wants them to articulate on paper how the two worlds compare and contrast.

“Writing is part of the job. If you don’t do the assignment, you don’t get paid. I dock you,” Brown says. Students are expected to show up on time. They are expected to do all of their work. It’s not for a grade, it’s for real money.

The former newspaper columnist has found that he still has a lot to learn.

“At one point I would have called myself the teacher. At one point I would have said employer. But it turns out I am the student,” Brown says. “I didn’t expect to be. What I hope to be is a validation. To make them feel validated.”

Not much longer after starting the project, he decided to document it. That has led to his first book, When We Listen, another way for Brown to secure funding for the program. In the self-published book, Brown uses his own experiences running the program to critique how community organizers must rethink their work with kids.

“I just hope I’m some kind of example, man,” Brown says. “Because, again, high school dropout, raised in poverty, got involved with drugs and the fast life, but yet, I found some value.”

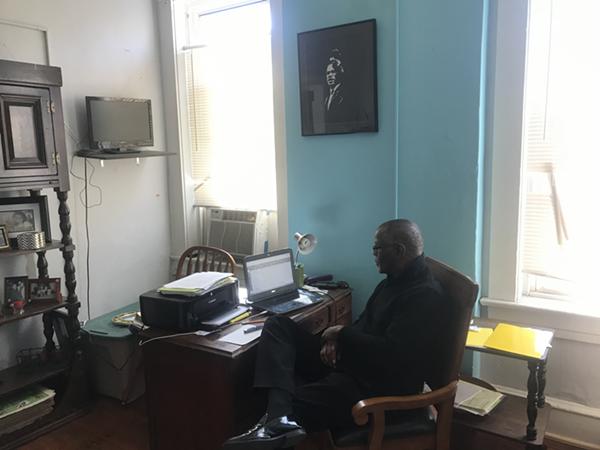

After an interview, it’s time to take a photo. The thing is, there are too many good spots. There’s the mural of America he painted on his living room wall one year ago. There’s the picture of Malcolm X, watching over Brown’s desk. There is the certificate from Washington University, there’s the framed photo of the first issue of Take Five Magazine, there are the endless photos of his children, there are the fresh plants sprouting throughout the room. He settles for multiple photos.

After that’s completed, Brown stands on the wooden porch, enjoying the spring weather and admiring the backyard. Staring right back is a mural, painted on the side of the connected building, featuring a bright-colored collage of St. Louis residents, history and structures. This one is also by Jamaica Ray. “Eclectic. Unique,” Brown says about the mural. “It tells the stories of St. Louis.”

To the side of the mural is a bed of dirt, with a few brown sticks popping up from the ground — the stems of Brown’s personal sweet potato garden. It looks bleak on this March day, but the energy of the mural makes up for it.

This is clearly not the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. There are no marble walls, no quotes from Joseph Pulitzer. But Brown is content. He is still writing, he is still drawing and now he has his sweet potatoes.

Editor's note: A previous version of this story referred incorrectly to Sylvester Brown's partners in Take Five Magazine. He was joined by his wife and Jabari Asim; an editing error wrongly conflated the two. Also, our reference to how many years passed between Brown getting into reading and being hired by the Post-Dispatch was incorrect. Twenty-five years passed, not twenty. We regret the errors.