In the wrong hands, The Winter's Tale is a whiplash inducer. Roughly the first half of the play charts an irreversible descent into rage and madness. The second half ascends in peals of laughter and inspiring reconciliation. If this journey of extremes is to make sense and ring true, the play requires a clear directorial vision to see it through.

So you may have some misgivings when you take your seat at Deanna Jent's Mustard Seed Theatre production, which imagines the kingdom of Sicilia as a hypermodern Seattle, with personal computers and business suits replacing Shakespeare's rapiers and doublets. The rival kingdom of Bohemia is the contemporary Alaska of the indigenous Tsimshian people, replete with totem poles and beaded buckskins. It's an audacious staging, at least until the actors go to work — then the choice of time and place sparks against the script, shining new light on the motivations of characters 400 years old and illuminating our own world.

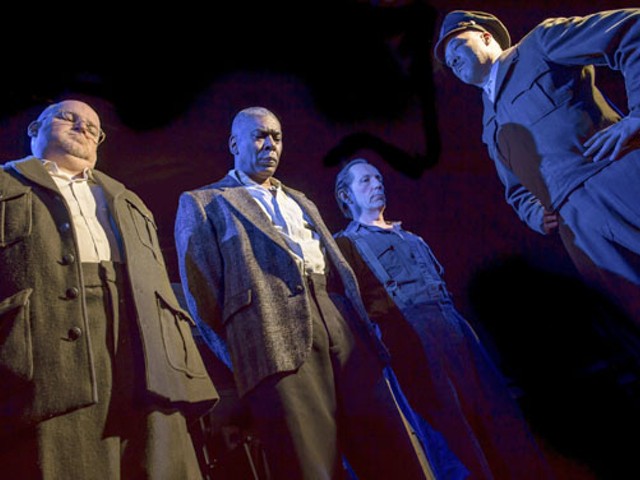

Take Leontes (Chauncy Thomas), the king/CEO of Sicilia: He has a beautiful wife, Hermione (Wendy Greenwood), a strong son and another child on the way; and his best friend, King Polixenes of Bohemia (Richard Strelinger), is in town. Good times, good times. Yet jealousy creeps into Leontes' mind: He suspects his wife is having an affair with his pal. The idea consumes him. None of his courtiers/staff can gainsay him, though all are convinced the boss is off his royal rocker. Leontes has his wife imprisoned and dispatches his buddy Camillo (Charlie Barron) to kill Polixenes — a task Camillo is understandably conflicted about taking on.

Contemplating his odious corporate duty in a desolate boardroom, Camillo attempts to psych himself up to murder an innocent man. "To do this deed, promotion follows," he reasons. (Doubtless that profound truth merits an entire chapter in Corporate Ladder Climbing for Ruthless Dummies.) Breathing a ragged sigh, Camillo chooses conscience over career and escorts Polixenes to the safety of Bohemia.

Through suave monologues punctuated by violent outbursts, Thomas carves Leontes' fury into a monument to hubris and the folly of temporal power. The deeper the king slides into fantasy, the more insectlike Thomas becomes, arms twitching and fingers fluttering accusingly at former friends. By the end of the first act, Leontes has denied his wife contact with their son, set their newborn daughter out to die of exposure and denounced his god as a liar. When he learns that his wife and son have died from grief and he realizes what he has done, that monument topples onto him and crushes him to his knees.

The second act is much lighter in tone and substance, concerned as it is with the blossoming love between Polixenes' son Florizel (Adam Moskal) and Leontes' daughter, Perdita (Laurel Elliot), who, as it turns out, ain't dead. There's a riotous comic interlude courtesy of Strelinger and Barron, who masquerade — ineptly, thanks in no small part to some awesomely fake facial hair — as an ancient prospector and "Sheriff Akimbo," respectively. But amid all the joy sounds a discordant note, in the person of Paulina (Kelley Ryan), Hermione's former confidante. Sharp-tongued and steadfast in her loyalty to the dear departed queen, Paulina mercilessly hectors poor Leontes about his fatal foolishness.

On the page Paulina is a shrew; in Leontes' lifeless boardroom Ryan portrays her as the unwavering voice of moral decency. Ryan delivers an astounding performance, resolute in demeanor and fiery in her outpouring. Paulina's is the voice of honor, love and fidelity in Sicilia — and it is through her that, by play's end, all are made whole. One can only wonder what might transpire if she were to materialize on Wall Street.