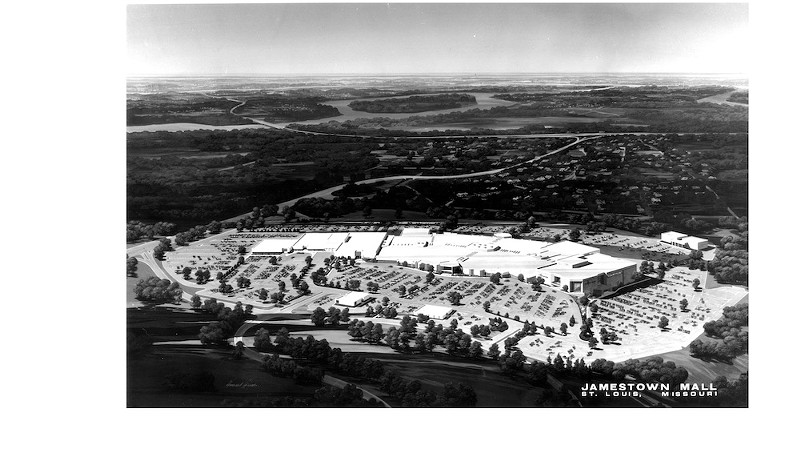

In the farthest reaches of north St. Louis County, against a dense backdrop of old sycamore trees and a sea of honeysuckle, the busy main road that we all know as Lindbergh Boulevard comes to a quiet and abrupt dead end. Steps away, a wild and secluded section of Coldwater Creek flows not far from the Missouri River. And it was here, in this seemingly remote and rustic area known as Old Jamestown, that somebody decided in the early 1970s it was a good idea to build a large enclosed shopping mall.

About eight miles to the south, the enclosed River Roads Shopping Center in Jennings had already been thriving for nearly a decade at that point. The indoor mall boom was also in full swing in other St. Louis suburbs, with Crestwood Mall (1957), South County Mall (1963) and West County Mall (1969) all beckoning shoppers inside from across the region.

So why not north county too? That’s what developers figured. And the idea of Jamestown Mall as a lush, climate-controlled shopping destination was born, all thanks to a partnership between two popular department stores — Stix, Baer & Fuller and Sears Roebuck — and an innovative Cleveland-based mall developer: Jacobs, Visconsi & Jacobs.

Groundbreaking started in 1972 on the site of what was previously a cattle pasture and several small family farms. Almost exactly a year later, Jamestown Mall officially opened for business on October 10, 1973.

It had 90-plus stores in almost 900,000 square feet, and sat on 63 acres of farm field, adjacent to even more farm fields and a smattering of newly built tract houses. And though it was basically in the middle of nowhere, it was also nothing short of a magical living terrarium: an always-78-degrees sensory experience, with huge skylights, tropical plants and trees, bubbling fountains, gleaming marble and several large contemporary sculptures that served as striking focal points in the main gathering areas.

It smelled of fresh earthy greenhouse and chlorine, mixed with a subtle hint of new shoes, movie popcorn, perfume and pipe tobacco. And the primary soundtrack was often gently flowing water plus a faint echo of organ music, coming from a salesman enthusiastically playing a keyboard at the music store by Sears.

I know because I lived in one of those nearby tract houses, just across one of those farm fields, starting in 1978 — and there was no place I would rather explore and wander as a kid than Jamestown Mall.

In 1981, while my mom was browsing the racks at Lerner, I asked if I could go to the mall’s center court where a small crowd was gathering around a temporary stage. As I walked up, the announcer welcomed a “soap opera star” with a “brand new record.” And lo and behold, I ended up seeing an early live performance of “Jessie’s Girl” by Rick Springfield!

I also spent countless hours in the '80s just hanging out at Jamestown Mall with friends. Crushing on boys. Playing video games at Aladdin’s Castle. Seeing my first 3D movie (Parasite … bad choice). Drooling over slouchy sweaters at the Limited and real parachute pants at Merry-Go-Round. Discovering waffle fries at the first-ever Chick-fil-A in St. Louis. Scouring Spencer’s Gifts for the latest Duran Duran pins and instructive books like The Valley Girl’s Guide to Life and Joel’s Journal and Fact-Filled Fart Book. (Still classics.)

I got my first job at the mall’s York Steak House at 14, after lying to say I was 16 and spending much of my short-lived career there sneaking pickles from the walk-in. I also worked at a women’s clothing store called Id, until the day I accidentally nicked a vein in my wrist while opening boxes, spraying blood all over the newest mauve-toned merchandise and nearly fainting. I was too embarrassed to come back after that, so I quit, but I still have a photo of my Id-approved work outfit: mauve + scarf + shoulder pads.

A couple years later, I met the legendary Muhammad Ali (!) when he was promoting his new cologne “for the man who loves to win” at a hastily draped folding table near Dillard’s (formerly Stix, Baer & Fuller). In fact, he was sitting right next to my very favorite sculpture in the mall, the smallest one and the only one not made of metal ... two intersecting concrete swirls that almost looked like the petals of a flower.

Little did I know then, but all of the mall’s sculptures were actually created by the same artist. I also didn’t know that the skylights were installed using helicopters. Or that the original east entrance could fully retract to allow trucks as big as a semi to enter.

And I certainly didn’t know that the mall’s manager from 1974 to 1979 was a creative showman of the highest order, or that ancient artifacts may have been discovered during construction, or that, in hindsight — let’s be honest — this is a mall that probably should have never existed. But I know now.

Inspired by news of the mall’s demolition, which started last month, I dove back into research I had started four years ago and re-connected with the sculpture artist’s wife and the son of one of the original developers. I also chatted with my friend Peggy Kruse, who just published her second book on the Old Jamestown area, and by pure luck I met a wonderful lady who once lived on the land where the mall was built.

Realizing I had a great story that needed to be told, I dug even deeper into research and talked to even more people who knew and loved the mall in its heyday. The result is not just a personal story, but something I hope anyone who’s ever visited a mall will find entertaining: My favorite “secrets” from the history of Jamestown Mall.

Yes, there was bear wrestling at the mall in the 1970s.

There was also a petting zoo with baby deer, a live Easter egg-hatching display with 120 candy-colored chicks, a large traveling lion exhibit where you could hold a lion cub and a visit by Kokomo Jr., the TV star billed as the “wealthiest chimp in America.” All of these animal attractions (and more) arose from the marketing genius of mall manager Ronn Moldenhauer, who also happened to be the first person to climb in the ring with the famous “Victor the Rasslin’ Bear,” at an event that drew wall-to-wall crowds to the mall in 1977, and where Victor’s 15,000-career winning streak was actually broken by a 19-year-old Olympic wrestler from Cool Valley!

A natural salesman and promoter who wore dapper plaid suits and sometimes a tuxedo and top hat, Moldenhauer had been running a women’s clothing store at another Jabobs, Visconsi & Jacobs (JVJ) mall in Michigan when the developer asked him to run the entire Jamestown Mall. He arrived a few months after the grand opening, at age 37, with a wife and three kids, and truly breathed life into the “mall as a second home” concept for Jamestown’s first five and a half years.

Envisioning center court as a town square, he welcomed puppeteers, pet owners, magicians, gymnasts, gardeners, Blues hockey players, skateboarders, military and school bands, woodworkers, disco dancers, square dancers, circus performers, fashion shows and “pretty much anything he could get in there that might interest more than five people,” says his daughter Laura Broccard, who worked numerous odd jobs at the mall as a teenager.

It was his idea to launch a Jamestown Mall newspaper and to create a costumed mascot named “King James the Lion,” sometimes played by his teenage son, who also played Santa Claus when the regular mall Santas called in sick. And of course it was Moldenhauer who planned events like the Tinder Box pipe smoking contest, the custom van competition, the iceless ice show, the Italian moped display, the annual “Datsun Fest” where you could win a new car by playing Wham-O Frisbee Golf, and the 1977 Farrah Fawcett-Majors look-alike contest, co-sponsored by radio station KSLQ.

More than 2,000 people showed up to see 108 “Farrahs” walk the stage and answer questions about their favorite movie star and favorite quote. Five semi-finalists were chosen that day, in a spectacle that the Post-Dispatch described as, “Lots of hair. Lots of leg. Lots of teeth.” Apparently Farrah contests were quite a thing that year, and Moldenhauer deemed his such a success that he immediately started imagining a Burt Reynolds look-alike contest as well.

But alas, he was offered the manager job at a bigger, newer North Carolina mall in 1979, and not only did the Burt contest never come about, but what was arguably the golden age of live events at Jamestown Mall came to an end.

The artist who created the mall sculptures was renowned and brilliant.

As JVJ was growing to become one of the country’s largest mall developers in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it built a stable of trusted contractors who would go project to project, state to state. And one of those “regulars” was a multi-talented artist from Cleveland named Clarence Van Duzer (1920-2009).

Known by friends and family simply as Van, he was a Yale-educated jack-of-all-trades who worked as a college art professor while simultaneously creating a stunning body of work in a variety of mediums. A skilled oil painter, sketch artist, model maker and muralist, he also crafted large abstract sculptures out of metal and concrete, including the rocket-shaped “Global Flight and Celebration,” a 50-foot-tall stainless steel landmark at Cleveland Hopkins Airport.

His work in malls spanned 11 states and encompassed not only sculpture, but also elaborate chandeliers and fountains that he designed, installed and maintained. “Van engineered all the plumbing, lights, electrical and cast cement pools,” says his widow, Kathy Lynn Van Duzer, “and I recall many times when he would pack his waders and head off to a mall to tune up the fountains and adjust the sprays.”

At Jamestown Mall, he constructed the massive copper sculpture at center court and the two steel sculptures in the north and south wings, plus all the fountains and cast concrete forms surrounding them. And yes, he also made the smaller concrete “swirls” by Dillard’s.

I was surprised to learn that he created sculptures and fountains for Chesterfield Mall too, and that those and all of his Jamestown sculptures very likely had names! Van Duzer titled nearly all of his pieces. But he was so prolific, constantly producing art, that his wife has yet to catalog his entire collection — so that will have to be a mystery for another day.

The fountains fed both plants and orphans.

Built as a giant living, breathing atrium, Jamestown Mall was also an enclosed ecosystem where the humidity from the fountains and the sunshine from the skylights provided an ideal atmosphere for tropical plants. For years, the mall employed a specialist in ornamental horticulture, who not only tended to pruning and fertilizing but also to propagating new plants from existing cuttings.

When the fountains were fully active (before they were mostly filled in with dirt in the mall’s later days), they supported a rich array of colored and textured flora, from Umbrella Plant, Ficus and Norfolk Island Pine to Dragon Tree, banana tree, Dieffenbachia and more.

The fountains also proved irresistible for swimming, at least to my then 5-year-old cousin Nick, who was one of many young kids who took the plunge. And you know those coins that collected at the bottom? For making a wish? Throughout the 1970s, they were gathered and used to throw an annual party for local orphans.

On the Sunday before Christmas every year, the mall welcomed around 400 orphaned children, who were given personalized gifts and treated to magic and puppet shows, a movie, photos with Santa, and a Thanksgiving-style meal with all the trimmings. Theater and restaurant workers donated their time.

“Mall employees, store employees, everybody helped out. Some of them even took turkeys home the night before and baked them,” the mall manager explained in a 1979 interview. “It was really worthwhile ... the whole mall coming together to do something like that for so many children.”

The parking lot probably hides ancient treasures.

In studying the history of the Old Jamestown area over the years, I’ve learned just how old it really is. Located not far from the confluence of two great North American rivers — the Missouri and the Mississippi — it was a land of natural abundance that attracted both indigenous people and frontier settlers. And before that …. WAY before that … it also attracted “megafauna” Ice Age animals, who gathered near a large lake that had formed at an ice dam near the mouth of Coldwater Creek.

That was 35,000 years ago, according to Joe Harl of the Archaeological Research Center of St. Louis, who says that since then, “Many Pleistocene animal bones have been discovered along Coldwater Creek … and numerous bones have been found during construction in this area.”

Which may help to explain a story I heard from a longtime Old Jamestown resident, who watched the mall being built: While earthmovers were clearing the land, she noticed a group of people with “little paintbrushes” working in a roped-off, square plot. She wasn’t able to get up close, but ended up talking with one of the crew, who told her they were archaeologists and had found, in her telling, “evidence of saber-toothed tiger!” She later heard that mastodon bones were found as well.

But unfortunately the earthmovers kept moving, she told me, edging ever closer to the roped-off plot, and within two weeks it was plowed over and filled in, soon to be covered with pavement.

The parking lot definitely hides sinkholes.

Of all the things that made Jamestown Mall unique, this was the one that sealed its fate: JVJ tried to get a jump on anticipated growth in the area and decided to build the mall before residential neighborhoods had really developed. And then somebody figured out — whoops! — the area is full of sinkholes and not conducive to high-density development.

Not only was the mall itself built on sinkhole land, in an area now recognized as “one of the finest examples of deep funnel-shaped sinkholes in the central United States” ... with known sinkholes at the mall site still noted today on Division of Natural Resources maps, but all of those new subdivisions and households that the developer had gambled on in the early 1970s basically never materialized, all due to the geological wonder known as karst/sinkhole topography, now officially protected in the Florissant Karst Preservation District.

Alton Square was the beacon of doom.

While the people of Alton may have celebrated their new mall in 1978, the manager of Jamestown Mall definitely did not.

As you can see in early advertising, one of the primary customer pools that JVJ had expected to tap was Madison County, Illinois. So when a new enclosed “square” opened just 11 miles across the river in Alton, in the heart of Madison County, it drew countless Illinois (and Missouri) customers away from Jamestown and truly hobbled its success moving forward.

What also didn’t help was the molasses-like process of upgrading nearby Highway 367, which would have allowed faster, easier access to Jamestown Mall from both St. Louis and Illinois. In the works for decades, it was finally completed in 2007 … one year after an original Jamestown anchor, Dillard’s, had already closed, and the mall was already many years into its long, slow death spiral.

The mall expansion in 1994 did add a Famous-Barr and a JC Penney, as well as 40,000 square feet of interior space and a new food court. But in my opinion, it actually ruined the vibe of the original mall concept and just felt kind of disjointed. I moved to Los Angeles a year later and didn’t visit Jamestown Mall again for quite a while. When I finally came back, honestly, the thrill was gone. The joy was gone. Most of the plants and fountains were gone! It just seemed like a bland, lifeless, patched-together shopping center desperately trying to hold on.

I was sad to see the mall finally close in 2014 after slowly declining for so long. I was even sadder when I started seeing videos online of looters and vandals violating the mall and its sculptures, and books showing photos of this “abandoned” vessel in its final descent. I found those very painful to look at, and still do.

When I saw the recent press conference with local politicians “celebrating” the mall’s demolition, I certainly had mixed emotions. I understand the need to remove a building that’s now an eyesore and health hazard, and I know that it’s taken a lot of work to get to this point. I hope this can be a catalyst for renewal in this corner of north county.

But for those of us who experienced Jamestown Mall in that brief window of time when it was really alive, this is not a cause for celebration. It’s a sad and bittersweet ending to the wonderful vision the developers had all those years ago. It’s also the loss of a physical space that was an architectural, horticultural and artistic gem ... and a lush and beautiful “town square” that offered anyone the chance to escape and enjoy it, even if you didn’t have a single dollar in your pocket.

So if there’s anything to celebrate, it’s our memories. All of us. The millions and millions of memories — good, bad and otherwise — all created in this far-flung, destined-to-fail, magnificent jewel box where we shopped and worked and gathered for 41 years.

Farewell, Jamestown Mall. You never should have existed, but you sure were loved!

Shannon Howard is a St. Louis writer, old house realtor, and local history researcher and storyteller. She invites you to share your own mall memories at Remembering Jamestown Mall on Facebook.

Subscribe to Riverfront Times newsletters.Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed