Quick: What musical act was the American equivalent of the Beatles? The Byrds? Dylan? The Beach Boys? The Aerovons?

Wait. You’ve never heard of the Aerovons!? Well, I guess you can be forgiven since the Aerovon’s prodigious 1969 debut album was lost for decades. But if there was one band that was poised to be the American Beatles and the Next Big Thing, it was the Aerovons. They had it all — the talent, the songs, the look — all in the right place and at the right time. After all, the band recorded the album at the fabled Abbey Road Studios, where the Beatles themselves recorded nearly their entire catalog. And they were one of ours: The Aerovons were from right here in St. Louis.

The unlikely story of the Aerovons is centered around Tom Hartman, who started the Aerovons in 1966 when he was just a 14-year-old student at Bayless High School, perhaps an inevitable result of having discovered the Beatles three years earlier. It was December 10, 1963 — two months before the Beatles’ first appearance on Ed Sullivan — when young Tommy Hartman caught Walter Cronkite ending CBS Evening News with a short clip of the Beatles performing “She Loves You.” A few weeks later, he heard “I Want to Hold Your Hand” on KXOK radio, after which Hartman remembers rushing to Sears in Crestwood Plaza with his parents to buy the store’s last copy of the record, which he still owns today. “I had never heard a record like that with that much guitar in it,” Hartman tells me over the phone from his home in Florida. “John’s rhythm part is just chugging along from beat one. I was blown away.”

The young Hartman, who was already playing guitar at the time, became a fanatical Beatles obsessive: “I spent most of my time in my room learning all of their stuff,” he remembers. His first break into the music business was a brief stint at age 13 in a local band called the Dartels, who later became the Aardvarks. Hartman had met bassist Mike Wee in school and was dazzled by the band’s professionalism and polish and the fact that they had an actual manager (Chuck Conners, who ran the old Ludwig Music store in St. Louis). However, the Dartels fired Hartman after a few weeks — after all, the band already had a guitarist, and Hartman was at the time uninterested in singing. Thankfully, Hartman’s mother, Maurine, who plays a key role in the Aerovons’ story, eavesdropped on the heartbreaking phone call and afterward encouraged her son to start his own band, one he could never be kicked out of. The Aerovons were born.

Hartman picked up the band moniker while spending his eighth grade year in Florida, where his parents had tried to make a living before moving back to St. Louis in time for Hartman to attend Mehlville High School and, later, Bayless. In Florida, he had a buddy whose band was called the Aerovons, who themselves borrowed the name from a New York band that had misread a brand name, Aerovox, maker of amplifier tweeters. After Hartman’s friend disbanded his Aerovons, he gave Hartman his blessing to use the name for his own newly formed group.

The Aerovons, made up of a Bayless classmate and two older boys, became a cover band that specialized in raucous versions of Beatles, Who and Turtles hits with Maurine serving as the band’s manager, landing the Aerovons their first shows. “She was winging it, combined with studying on the job,” Hartman says of his mother’s alacrity for the music biz. “Mainly, my mom was somebody that if you said, ‘You can't do that,’ she’d say, ‘Get me the phone number.’ She was just very persuasive and strong-willed and got things done.”

For example, Hartman remembers a local music promotional event called Last Train to Clarksville, in which the top St. Louis bands would perform in train cars on a railway ride from St. Louis to Clarksville, Missouri, some 80 miles north. After overhearing Tom and the boys talking about how cool it would be to get on the Last Train bill, Maurine made a few calls and secured the Aerovons a spot on the musical train, despite the band being relative unknowns. “She was crazy,” Hartman now says with obvious affection.

Soon, the Aerovons were playing all over town, and the band was a local hit. By then, Hartman had warmed up to singing and was the band’s frontman, doing his best John Lennon and Roger Daltrey. “We were a much heavier, rockier group,” Hartman says, compared to the original music the Aerovons would later make.

Hartman rattles off the names of St. Louis clubs the Aerovons played (Castaways, Bat Cave, Rainy Daze). They even opened for the Temptations and played during the seventh-inning stretch at Busch Stadium, until one day his mom prompted him to take the next step and write some original material. Hartman had picked up the piano from his older sister, a gifted piano major in college, and in 1967 sat down to write his first song.

“In very short order I came up with ‘World of You,’” he says. “It was just kind of meant to be. I just hit those chords and started singing.” “World of You” came out as a lovely, baroque-pop ballad about falling in love for the first time, a phenomenon that Hartman admits he had little experience with at the time. “I really hadn’t [fallen in love] by that point,” he says. “But I’d been girl crazy since probably kindergarten, so I imagined what it would be like.”

In any case, the song, with its undulating piano lines and Hartman’s conspicuous impression of a British accent, would unlock many of Hartman’s youthful dreams. His mom scraped together the money to have Hartman and his bandmates make a recording of “World of You” at the old Premier Recording Studio in St. Louis. As luck would have it, St. Louis was home to a distribution center for Capitol Records, and one of the label’s employees happened to stop by Premier to hear what the studio had been recording lately.

The employee, taken with the Aerovons’ “World of You,” gave the Hartmans a call, offering the band a meeting with the label out in California. Maurine struck again. “She told the guy that her son really had his heart set on going to London to record where the Beatles do,” Hartman remembers.

Against all odds, Maureen was indeed able to get an appointment with EMI, Capitol’s parent company, in London, and in 1968 after raising some funds from family friends, the four Aerovons — Hartman, guitarist Bob “Ferd” Frank, bassist Nolan Mendenhall and drummer Mike Lombardo — flew across the pond along with Maurine. There, they met with Roy Featherstone, legendary A&R man for Queen, at EMI’s offices in Manchester Square, where the Aerovons recreated the famous photo of the Beatles looking over the railing of the building’s stairwell. Featherstone listened to “World of You” and agreed that there was enough there to work with the Aerovons.

Time for another Maurine maneuver. In addition to talking to EMI, she secured a meeting with Decca Records in London, attempting to spark a bidding war for the Aerovons. At Decca, the Aerovons were wooed by A&R head Dick Rowe, the man who had infamously passed on signing the Beatles. Rowe looked at Hartman and said, “I’m not going to make the same mistake twice.”

“I had no idea what he meant,” Hartman says now. “Only later when I read about him did I realize that this was the man who turned down the Beatles.”

Decca producer Tony Clarke, best known for his work with the Moody Blues, even took the Aerovons over to the Moodys’ flat, where the young Americans met the British art-rock stars. And while Decca had yet to make an official offer, Maurine, in another display of shrewd business acumen, bluffed EMI into one anyway. “She told EMI that Decca offered us $3,000 as an advance,” Hartman says with a laugh. “And EMI matched Decca’s nonexistent offer.”

Also during that first trip to London, another of the 17-year-old Hartman’s wildest dreams came true when he gained access to the private Speakeasy club, hangout of the stars, where he met Paul McCartney himself. Michael Caine and Diana Ross were also at the club that night, but when he spotted McCartney, Hartman knew it might be his only chance to talk to his hero. “I was being nudged by my bandmates toward Paul, and I walked up to him and said, ‘I’m so sorry, Paul, but we’re from St. Louis. Would you have just a couple of minutes to talk?’ And he leaned back and said, ‘Yeah, sure! Where are you from?’”

When telling these stories, Hartman replicates a spot-on Liverpudlian accent, and he modulates his tone and inflection among the Fab Four with remarkable fidelity. But it was the guitars he wanted to mimic in those days. He recalls, “I was on a mission to find out how the Beatles got their guitar sounds, so I asked Paul if he remembered how they did the guitars on ‘Nowhere Man.’ He said, ‘Yeah, it was a Gretsch with a lot of top put on,’ meaning treble.” McCartney also signed four Aerovons business cards, one for each member, and, according to Hartman, got a kick out of the tag line on the American band’s business cards that advertised “Smashing English Sounds.”

“He was so nice and pleasant and funny,” Hartman remembers. “I still have that card firmly framed on the wall here [at home].”

Two days later, the Aerovons toured EMI Studios (later renamed Abbey Road Studios), where storied Beatles road manager Mal Evans, whom Hartman recognized from his ice-swimming cameos in the film Help!, personally showed them around. The boys were awestruck when they walked by Ringo’s drum kit with its distinctive “LOVE” bass-drum head from the recently released Magical Mystery Tour. But the real thrill was when Hartman looked up and spotted George Harrison through a window to the control room above them, where the Quiet One was working on a solo project.

In a moment of nothing-to-lose boldness, Hartman caught Harrison’s attention and gestured for him to come down to the studio. “He immediately turned his back and disappeared from the window,” Hartman recalls. “The next second, the control room door opens and George looks down and says, ‘Are you with a magazine?’ Because my mom was standing there holding a camera. And I said, ‘No, we’re a group. We’re going to be recording here.’ And he said, ‘Oh, OK.’ And he came down and walked over to us, and we were all just dying. And it turned out to be just wonderful. We got to talk to him for a while, asking him guitar questions he couldn’t remember most of.”

One of those guitar questions was again about “Nowhere Man,” to which Harrison explained that the guitar break was rendered by Harrison and Lennon playing two Fender Stratocasters together. Hartman was quick to tell George that Paul had given him a different answer. “I told him, ‘We met Paul the other night, and he said it was a Gretsch,” Hartman says. “And George said, ‘No, it was two Fenders.’”

After finding out that the Aerovons were from St. Louis, Harrison brought up his 1963 trip to southern Illinois to visit his sister, Louise, the first time any Beatle visited America. “I ended up in some little hick town,” Harrison told Hartman, a reference apparently to Benton, Illinois, where Louise lived. “Like a dummy, I asked him if he remembered playing at Busch Stadium, and he said, ‘Vaguely,’ which means no,” Hartman recalls with a laugh.

Maurine snapped several photos of Harrison talking with her son’s band, and in the one photo of the meeting that survived, the four mop-topped Aerovons wearing their colorful newly purchased Carnaby Street threads are nearly indistinguishable from the Beatle they idolized.

Told by the label to go home and write more material, the Aerovons returned to St. Louis. Hartman would have been a senior in high school but did not return to school, focusing instead on writing and recording demos for a promised trip back to London a few months later. What does a St. Louis teenager, who had just rubbed shoulders with a couple of Beatles and had landed a record deal where the Fab Four themselves record, do with that assignment? In Hartman’s case, he wrote a dozen songs filled with those Smashing English Sounds.

“We wanted to go in the Beatles’ direction, which was to have as much variety as possible,” he says. “We didn’t want to keep writing the same song. We thought ‘World of You’ was really neat, but we didn’t want to write another ‘World of You.’ We had grown up learning and playing and listening to [the Beatles] do everything from ‘Hard Day’s Night’ to ‘Lovely Rita,’ so we were always thinking about what we could do next.”

While the other Aerovons also took stabs at writing songs, Hartman ended up being the band’s de facto songwriter and ended up with more than a dozen songs cheaply recorded in the basement to take back to London. However, the band would have to shuffle its lineup before heading back. Bassist Nolan Mendenhall was swapped out for drummer Mike Lombardo’s brother, Billy. Longtime rhythm guitarist Bob Frank, who was terrified of being drafted and sent to Vietnam and didn’t want to risk being in England when it happened, was replaced by guitarist Phil Edholm.

In the meantime, in the pre-fax late ‘60s, Hartman and his mother had to fly back to London just to sign all the legal documents tied to the Aerovons’ record deal with EMI. During this short trip, Hartman again visited EMI Studios where he experienced another brain-reorganizing thrill of a lifetime. When he inquired of an older gentleman working the security desk which acts were recording that evening, the man said, “Well, the boys are here tonight.”Hartman suspected he knew who “the boys” were and found his way into the studios’ hallways. “I heard this horrendous, loud guitar, and I look over to my right and crammed into this tiny room were all four Beatles doing takes of ‘Yer Blues,’” Hartman says. “I remember someone from the control room said something, and John said, ‘That’s okay as long as you’ve got the vocals,’ and everyone laughed.” During another studio visit on that trip, Hartman overheard McCartney doing vocal overdubs of “Sexy Sadie” — a song, like “Yer Blues,” that Hartman would recognize when the White Album came out a few weeks later.

In March of 1969, the retooled lineup of the Aerovons returned to London to record “World of You” and, hopefully, the new songs, as well. EMI liked one called “Everything’s Alright” and agreed to record it, too, before gradually warming up to the others and agreeing to cut a full album.

More mind-boggling brushes with greatness followed: Hartman met Pink Floyd and the Hollies at the studio. He ran into Jimi Hendrix on another visit to the Speakeasy, asking him how he keeps his guitar in tune during his maniacal live shows. (“You just gotta tune why you play, man,” Hendrix told him.) Hartman also chatted with Beatles producer George Martin about Hartman’s favorite subject, guitar engineering logistics.

And at one point while recording, Hartman borrowed a guitar cable from John Lennon. After his own cable malfunctioned, Hartman spotted Lennon in a hallway talking to Yoko. “I walked up and said, ‘Excuse me, John. We’re recording in the studio, and we were wondering if we could borrow a guitar cable from you.’ He said, ‘Do you know Mal or Kevin? Go tell them I said it was OK.’ I walked away, and I was just shaking.”

For three months in London, the Aerovons crafted an exquisite 12-song collection of ‘60s orchestral pop across a variety of Beatlesque styles, engineered by the Fab Four’s own technicians, including Geoff Emerick and Alan Parsons, and produced, for the most part, by Hartman himself. Listening to the tracks today, it’s astounding that such beautiful, sophisticated songs, many of which could easily be mistaken for lost Beatles outtakes, were primarily the work of a teenager from south St. Louis county who had never made a record before.

Trouble eventually found its way into the recording sessions. Unbeknown to the other Aerovons, guitarist Edholm went to EMI executives to complain that Hartman would not allow the band to record any of Edholm’s compositions. According to Hartman, the label agreed to listen to Edholm’s songs, sided with Hartman that Edholm’s songs weren’t strong enough, and sent Edholm packing back to St. Louis. Suddenly, the Aerovons were a trio.

Other lore that hovers around the Aerovons is that the Beatles might have based “Across the Universe” on the Aerovons’ similar-sounding “Resurrection,” a theory that Hartman is quick to discount, insisting that the reality is, at least in part, the other way around. One day in the studio, one of EMI’s engineers gave Hartman a sneak peak of the yet-to-be-released “Across the Universe,” which would later appear on Let It Be. “I was blown away,” Hartman says. “I thought it was just wonderful. I heard it one time, and I obviously heard it too well.” Hartman says that while the chorus for “Resurrection” was actually inspired by an Engelbert Humperdinck hit, other parts of “Resurrection” are too close to the Lennon-penned “Across the Universe.” “The verse was just too lifted,’ he says. “I still think [“Resurrection”] is a pretty song, but given my druthers, I would pull it off [the Aerovons album].”

Imagine being a teenage Beatles worshiper from the States who miraculously finds himself in Abbey Road’s Studio Two in 1968 between Magical Mystery Tour and the White Album — surrounded by the Beatles’ gear and engineers and even sometimes the Beatles themselves. Given such extraordinary circumstances, how could the music not end up sounding derivative? What’s amazing is how fully formed the band sounds instrumentally and how mature Hartman’s songwriting is on the album.

And while Hartman expresses a few misgivings about the way the album turned out, he admits that “90 percent of the album is really well-rehearsed. The musicianship on that album is really good. Mike was great. Billy plays insane bass parts. I think it was tastefully done musically.”

Others agreed. EMI engineer Alan Parsons, who would go on to have a series of Top 40 hits in the ‘70s and ‘80s as the Alan Parsons Project and who remains good friends with Hartman today, thought the Aerovons were headed for the big time. “He always tells me that everyone thought we were going to be the next big thing,” Hartman says.

But the Aerovons were not the next big thing. In fact, within days of finishing the album, the Aerovons were hardly a thing at all. As soon as they landed back in St. Louis, drummer Mike Lombardo left the band to focus on patching up his marriage. EMI wanted the Aerovons to be a four-piece band like the Beatles; now they had to wonder how the band was going to tour and do promotion for the album if they were down to two members. Moreover, the first single, “Train,” failed to get much airplay, nor did its follow-up, “World of You.” So with the band crumbling and their singles stalling, EMI decided to shelve the album indefinitely.

EMI still believed in Hartman’s talent and offered to have him come back to London alone, perhaps to join forces with Parsons, and have a fresh start. But Hartman balked at the offer. “I was a stupid kid,” he says. “I had just gotten back from not being able to find any food at all in London. I just wanted to kiss the ground that I was back in St. Louis. They wanted me to move permanently back to London. I didn’t want to do that.”

There was, however, the matter of the Aerovons still being under contract with EMI — and that was, obviously, a job for Maurine. A longtime Frank Sinatra fan, Maurine somehow got in touch with Sinatra’s attorney in California and asked him for help with the EMI contract situation. Through circumstances that Hartman doesn’t quite understand, the lawyer phoned the Hartmans after having traveled to London and informed them that they were free and clear of EMI.

Back home, Hartman flirted with a solo career in California, releasing a harder-rocking single, “Sunshine Woman,” with Bell Records in 1971, before ultimately opting for college and leaving his pop-star ambitions behind. Hartman first attended Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville before finishing a music degree at the University of Miami. He’s lived in Florida ever since.

Hartman has never stopped making music. For almost 50 years, he has enjoyed a successful career scoring documentaries and commercials. He calls himself a “music producer gun-for-hire” and considers himself blessed to be making music on a daily basis as a way of supporting his family, which includes five children.

Still, the legend of the Aerovons refused to die. A few years ago, a music journalist in England reached out to Hartman and asked if he realized that the Aerovons’ lost 1969 album had leaked and was being bootlegged all over Europe. “He told me that he could go into record stores in London and buy the album for $45,” Hartman says. Subsequently, RPM Records acquired the album from EMI and released it in 2003 under the title Resurrection. “My first thought was, ‘Oh, no, now everyone is going to hear it,’” Hartman jokes. But after 33 years lying dormant, the Aerovons' long-lost debut finally saw the official light of day, and the album and Tom Hartman’s curious story were in high demand among Beatlemaniacs everywhere.

To this day, Hartman is Ressurection’s toughest critic and doubts that the album would have been a hit if EMI had indeed released it when it was new. “There’s nothing commercial about the album,” he says. “It’s a soft album. There’s nothing you can dance to on it. It’s just too dreamy.”

Which is why Hartman wanted to take another shot at making some Aerovons music that he describes as a more mature, accessible set of songs than what he came up with as a teenager in London. “I heard a lot of freshman mistakes on the British album. I was 17. I tried to do another release of stuff just to do something better. It’s more of what I wish the British album would have been.”

And so in 2021, Hartman released the second-ever collection of songs billed as the Aerovons, the critically acclaimed A Little More, filled with Smashing English Sounds, shimmering power pop a la Wings, indelible hooks and ravishing instrumentation. The songs were written over a long period of time with the title cut dating back to the early ‘70s and “Swinging London” representing a new song about old times.

A Little More is currently available on streaming services, but Resurrection has yet to be streamable, and Hartman isn’t certain why. (He told me he would look into it. In the meantime, you can find the full Resurrection audio on YouTube.)

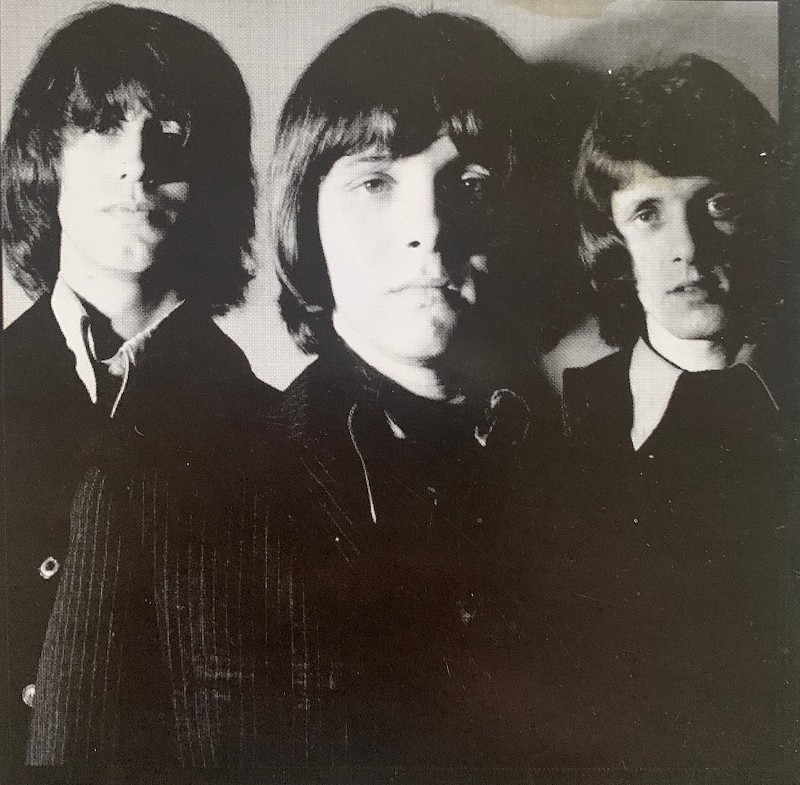

Now, nearly 55 years in the making, Resurrection is finally being released on vinyl for the first time with a new remaster and a classic flipback sleeve with the original artwork and photograph of the Aerovons taken in a London park. The album will be available exclusively at Euclid Records for the first three months of the release, starting on Record Store Day, April 20, and then will be distributed to independent record stores throughout the U.S.

Hartman says that he hasn’t been back to St. Louis since the 1976 bicentennial but that he would love to revisit his old stomping grounds and take his kids to 7938 Kammerer Avenue to show them where all the Aerovons songs were written. Among his old bandmates, Bob Frank is still living in St. Louis. After the Aerovons, Frank played bass for John Cougar before he was Mellencamp. That’s Frank’s bass on Mellencamp classics “Jack and Diane” and “I Need a Lover.” The Lombardos, however, have both passed away — Billy in 2012, Mike in 2016.

If Hartman has any lingering sadness or bitterness over what might have been with the Aerovons, he won’t admit to it. He insists that his dream of recording at Abbey Road came true, that any money he might have made back then would be long gone, that he has had a rewarding musical career anyway and that he is enjoying the flattering resurgence of attention the Aerovons are getting.

The story isn’t over. Now 72, Hartman says he continues to write and has several songs that could turn into another Aerovons album in the future. Plus a screenplay is being developed to tell the Aerovons’ story. (Who do you think should play Maurine Hartman in the movie?)

And while Hartman has not played an Aerovons show in a half-century, he does not rule out the possibility of staging an Aerovons concert to play the old songs live if given the right opportunity. “That would be a lot of fun,” Hartman says. “But I’m not sure how realistic it is.”

Where else but St. Louis for such a landmark event? It’s finally the right time for Resurrection. And in that spirit, it feels like the righttime to bring the Aerovons home for a celebration that is long overdue.

Subscribe to Riverfront Times newsletters.Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed