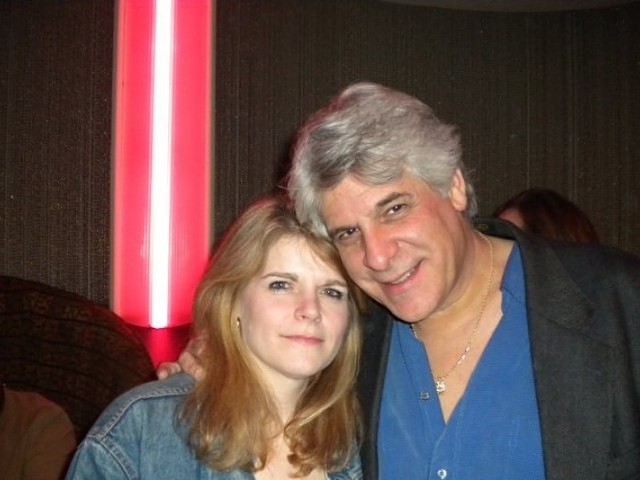

A friend for four decades, Patty Maher has lots of stories about Bob Burkhardt, dating back to his years as one of the key builders of St. Louis nightlife, especially in Soulard. These days, though, Burkhardt has a tendency to change phone numbers. If he doesn't return 25 calls, Maher explains, she has been known to just show up at his doorstep.

And so it goes this November: Maher barreling down Interstate 44, westbound from the city, taking a 30-minute drive in significantly less than that, her Ford F-150 covering ground in leaps and bounds. A green builder by trade and a storyteller by nature, Maher is adept at spinning tales of Burkhardt's days as one of the St. Louis' great pickers.

Maher knows both buildings and the acts of repurposing them, and she's got lots of ideas on how her onetime squeeze, Burkhardt, was able to wed his own free spirit with the more mundane aspects of development.

See also: 27 Incredible Photos of Artists in St. Louis' Gaslight Square

A person can get lucky with one club, hitting on a formula and making it work. But to do it again and again suggests something more elusive — if not quite a gift, at least a talent. Bob Burkhardt, over the span of a couple decades, hit paydirt with every club he opened.

Getting the stories from the source himself means driving to a slip of a town called Crescent, which shares a post office with neighboring Eureka. Save a stint in prison, Burkhardt has lived there for about fifteen years in a house that's part home (for him and daughter Tina) and part antique shop. It's filled with period furniture, display cases of arrow heads, mounted animal heads and other assorted bric-a-brac.

When Maher's first knocks on the door don't bring a host, she just pops in and yells his name. No response.

She changes gears.

"You've got to come around the back first," she decides. "He's got this beautiful limestone grotto."

Sure enough, with the aid of an earth mover and stones culled from this place and that, Burkhardt has crafted a striking stone wall, cropping out of the Missouri clay and centered by a pond created from scratch.

As Maher stares into the wintry water, a sound emerges from behind her, and there he is, an important figure in the history of St. Louis Hip — clad, at this moment, in a white terry-cloth robe and slippers. He invites his uninvited guests in, changes into daywear and subtly asks Maher to head into town for some whiskey and beer.

Then the stories promised by Maher come, spread out over a couple of languid hours; they roll a bit more freely once Maher's completed her run for some smokes and Budweisers and Jameson.

Asked about the grotto, for example, Burkhardt says, "I brought in a Bobcat, a skid loader. I was doing some other stuff around the city, and I was getting these stones. I had a van, but not a plan." He pauses, for effect. "I do plan on having some of that Jameson, though."

So he has another Jameson and they swap more stories, many of them known to a group of St. Louis' bohemian sixty-somethings, but not the general public. Indeed, mention "Bob Burkhardt" in Soulard and most of the kids drinking there have no idea who he is. Time has moved on, and so has St. Louis' bar scene.

But Bob Burkhardt — the man who made St. Louis nightlife what it is today — isn't done yet. In fact, he just might be ready for one more go.