Police officers with their guns drawn swarmed Bade Ali Jabir's apartment. They were everywhere. Outside the door. Outside the window. In front of his neighbor's door. Everywhere. They yelled over a loudspeaker in Arabic, a language he sometimes struggled to understand. They told him he had to leave his apartment.

The police said that Jabir had been evicted and there were warrants out for his arrest. But Jabir didn't trust these people with guns. He trusted his friends, the people who brought him food, stayed with him in the hospital and fed his kids. It took time before he told you about his life in Sudan. And after Jabir's decades of living through the Sudanese civil war, gaining his trust wouldn't happen by putting a gun in his face.

So Jabir didn't leave. He hid in the apartment as the people with guns outside of his window only seemed to multiply.

No one knows what went through Jabir's head that day. Maybe he thought about his four kids. Maybe he was confused. Maybe he didn't realize that he had been evicted.

Whatever he thought about, he must have flashed back to Sudan. Five years before, Jabir emigrated from his ravaged homeland to the United States. Villages were burned to the ground, and citizens were shot on sight by government troops. Jabir came to America to escape from that terror, where people in uniforms regularly pointed guns at him.

On this day, September 7, 2022, the challenges of Jabir's new life and the years of trauma from war and migration came to a boil. Jabir, more than anything, needed help.

A few hours after the officers with guns surrounded his apartment, they sent in a remote control robot to communicate. It rolled in with a fuzzy microphone and a fuzzy camera, and the voice coming from it was the voice of Jabir's friend, a fellow Sudanese refugee.

"I'm scared," Jabir told the robot.

He asked his friend to come inside, to walk out with him.

The friend never did come. Instead came the officers with guns. That's when St. Louis police killed Bade Ali Jabir.

When Jabir walked off the plane in St. Louis in 2017, no family members or friends waited for him at the airport. He likely didn't know a thing about the Arch or toasted ravioli — or anything else about St. Louis. Why would he? His home was a village in the Al Kurumik district of the Blue Nile state, more than 7,000 miles away, where the Ingessana people lived, barely north of the South Sudan border.

Jabir was from a hilly rural area known for seasonal farming, according to a friend also from Sudan. He says Jabir worked with livestock, farmed a plot of land for a few months and then stored the food for the rest of the year.

The area was known for its music. "His culture," says the Sudanese friend, "they like to sing and dance." It was communal. Neighbors would make their own alcohol for these special occasions, and everyone would come together to sing and dance as a village and as a family.

But then he had to leave. Jabir was born in 1961, and armed conflict and genocide loomed in the background of his entire life. He lived through two civil wars before government bombings forced him to flee in 2011. The Blue Nile state was situated in a precarious place. Despite siding with the South Sudan-based Sudan People's Liberation Movement during the wars, the state was excluded from South Sudan when it seceded in 2011. Relations between the Sudanese government and the Blue Nile state were tense.

Then, on the night of September 1, 2011, gunfire rained down. The Sudanese government bombed the Blue Nile state, razed mosques and schools, and indiscriminately killed kids and the elderly. People were burned in their homes. Those who stayed had little to eat and almost no clean water. Between 2011 and 2013 alone, nearly 150,000 people fled, some walking for days to Ethiopia or South Sudan.

So Jabir left, too. He found himself in a U.N. refugee camp in Ethiopia. Indran Fernando, Jabir's caseworker at the St. Louis-based International Institute, calls conditions in the camp "hellish." During the day, Jabir worked long hours in the hot sun. There were days when the camp had so little food that he had to choose whether to feed his kids or give the food to people who were starving to death.

When Jabir arrived in St. Louis in 2017, he left behind everyone he knew: his father, his brothers and sister, his three sons from a previous marriage. His mother and brother had recently died and his wife passed away while giving birth to twins. Jabir came to a new country, a single father of four young kids. In his culture, women take care of the children, Fernando says, and Jabir seemed to have little experience parenting.

Jabir didn't have family waiting for him in St. Louis, but he did have Fernando and the International Institute. The institute, which did not respond to multiple requests for comment, is paid by the federal government to give short-term help to refugees resettling in St. Louis. Fernando was in charge of acclimating Jabir to St. Louis, getting him a job, signing him up for medical services and teaching him things like how to use an ATM and hygiene expectations.

And for Jabir, newly settled into an apartment just off South Grand in Dutchtown, plenty of things felt unfamiliar. The humid weather. The taste of fast food. The beer. The health care system. The work expectations. The concrete and speeding cars outside of his window. The English language, which he didn't understand, making it hard to do almost anything –– order food at a restaurant, read signs on the road, say hello at the grocery store.

Even seemingly basic tasks in America were new to Jabir. Fernando remembers that Jabir didn't know how to sign his name. The first time he spoke through a telephone, he seemed in awe. He poured water on the ground as if it were a dirt floor, others say. He didn't know how to use appliances like a refrigerator, bathtub or washer and dryer.

Jabir was also isolated. Bilingual International Assistant Services Executive Director Jason Baker says the Sudanese community in St. Louis is "very small." Few people were familiar with his home, or spoke his first language (Gaam), or understood his trauma, or knew about his culture, or could even find Sudan on a map.

Christopher Prater, a Washington University physician who works with immigrant communities through Affinia Healthcare, says he sees "high rates" of anxiety and depression among refugee communities.

"Could you imagine," says Prater, "stepping into a world where you don't understand anything? And all of that happens at once?"

Jabir found himself alone, raising four kids without much of a blueprint, in a country he did not know, without family to help, without knowledge of the language, in a place that seemed to move a little too fast.

"This is my speculation, but the vibe that I got was just adjusting to living in America was really hard for him," a neighbor says. "I am not sure that he ever really felt like this was home."

But Jabir didn't complain, Fernando says. He tried. He held a job, at first. He rode his bike to Arab grocery stores and picked up groceries. He took English classes and cooked chicken, on occasion, for his family.

"He was just endlessly patient," Fernando says. "Trusting, generous, unflappable. That's how I would characterize him. He had been through such difficult hardship that he expected very little from this country."

Despite his efforts, Jabir struggled to care for his kids amid all of these adjustments. The news reached a social worker with the Islamic Foundation of Greater St. Louis.

When the social worker met Jabir at his apartment around October 2018, it was a cold day. His kids were playing outside, but some didn't wear coats. One was barefoot. The social worker could tell none of them had bathed recently.

In Jabir's apartment, the situation was even more dire. The apartment was a mess. The social worker found toilet paper stuffed into the bathtub and roaches, rats and mice running across the floor. The kids had plenty of clothes, but Jabir used them as rags.

The social worker pauses before sharing those details, wondering how it will reflect on Jabir. But she decides to continue.

"I want to showcase that mental health is real," she says. "And I want to show that the police didn't care that he had a mental health problem, and that they still proceeded to do what they did."

By all accounts, nothing made Jabir happier than his kids. He was affectionate with them. Fernando watched Jabir console them after nightmares. He fluffed up their pillows before bed. He hugged them and stroked their hair. They were among the few things that could make Jabir smile when they played his favorite songs or made a joke. "I'm doing this for my kids," he often told the social worker. When Child Protective Services later threatened to take away his kids, he pounded his chest. Over his dead body, he said. "I am their father and their mother."

Jabir wasn't without help. Immigrant organizations, religious groups, members of the Sudanese community, doctors, therapists and, most importantly, neighbors did what they could. After a social worker met with Jabir, the Islamic Foundation covered the family's rent, bills, clothing and doctor appointments.

In 2019, the foundation helped relocate Jabir and his kids across the city to the Garden Apartments on Hodiamont Avenue. The north city complex has been home to many refugees and new immigrants in recent years. Yet, in 2018, the International Institute suffered a spate of negative press after Syrian refugees placed there complained that they feared for their safety. In one instance, four Syrian kids were attacked by neighborhood youth, and one ended up in the hospital. The International Institute no longer contracts with the complex.

For Jabir, however, the move seemed to make sense. The Islamic Foundation paid a Sudanese neighbor at Hodiamont to watch the kids, take them to dentist visits, visit their school and clean the apartment. Some of the kids called her "mom" in Arabic.

Over the years, she wasn't the only person who became attached to Jabir. Another neighbor went to the house every day to clean, buy groceries, watch the kids and feed him medicine. A fellow Sudanese refugee brought Jabir his favorite food –– chicken wings with lemon pepper. A woman who lived across the city visited him weekly for five years.

But no matter how much money, time or help Jabir received, little seemed to improve.

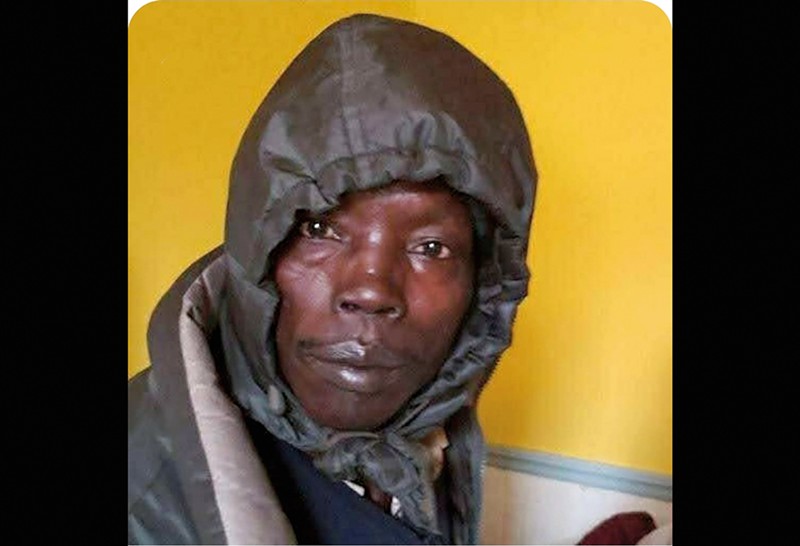

On good days, Jabir enjoyed being outside. He didn't go far, just a few steps away from his unlocked door, either sitting in a dining room chair or leaning against the brick wall of his apartment. It was his escape. He would bask in the fresh air. Skinny and wiry with soft facial features, he often wore a button-down shirt, black aviator sunglasses even if the sun was setting and a dark brown coat even if it was blazing hot. "Pondering life," one neighbor called it.

In America, there was a short list of things that seemed to make Jabir happy: his kids, company from friends, Arab tea with lots of sugar, chicken, Sudanese music videos, memories of Sudan and sitting outside.

If you approached Jabir on these days, he was warm, easygoing and calm. When a fellow Sudanese refugee brought him food, Jabir would bow his head, out of respect.

He cherished the opportunity to socialize with his people. If you came to see him, he'd grab a chair from his dining room and set it so you could sit beside him. Then he might share his memories from Sudan. He might walk over to his neighbors, the Sudanese family, and laugh with them.

"He was just a kind person," says neighbor Dalia Atak. When kids came over to visit, he would announce their name with an upbeat, high-pitched voice, and then gift them a piece of watermelon or croissant. He cherished the opportunity to share food. Food wasn't just something to eat. It was a form of affection. When his kids returned with food, he often told them to share with others in the community.

"Something I saw was endless generosity," Fernando says.

But Jabir could also seem lost. The last two years of his life, Jabir rarely left the house. He wouldn't walk to the park across the street or ride his bike. Someone would get groceries for him, take his kids to school and drive them to the doctor.

On his worst days, Jabir wouldn't go outside and sit on the lawn. The door would be closed but never locked. Inside, it was pitch black. Bare, no decorations. Mice scurrying around, holes in the walls, doors off the hinges, sink clogged, water dripping from the ceiling, sometimes a bed in the living room and one time a raw chicken on the floor.

If you asked how he was doing, he would always say the same thing –– "good." But he didn't seem good. He might curl himself into a ball on the couch or bed, a blanket cloaked over his head. Sometimes, Jabir would hide like this for days on end.

At times, Jabir seemed to be somewhere else. If people tried to engage in conversation, he would go on incomprehensible rants or simply not respond. "It was like, 'Who is this guy?'" the fellow Sudanese refugee says.

He seemed paranoid. He feared signing documents, and he told Atak that imaginary people in the apartment spoke to him. He wondered whether the people who lived above him had put a curse on him –– and if that's why he felt sick.

Toward the end of his life, these bad days became more frequent. The worker at the Islamic Foundation wonders if it dated back to a bike accident he had with a car when he lived on Grand. After that, he stopped riding his bike and stayed home more. Or maybe he just felt lost in America. Regardless, he fell into a gradual, but steady, decline.

In the summer of 2021, a neighbor of Jabir's reached out to Christopher Prater, the Washington University primary care physician. Jabir needed help. He was in constant pain, with a serious health problem that left his body swollen and bloated.

But there was one issue: Jabir wouldn't leave the apartment.

"There was something about him that made him very hesitant and fearful to leave," Prater says.

So they scheduled a video call with an interpreter. As Prater walked through introductions, Jabir struggled to understand the interpreter's Arabic. He made baffled faces and spoke little.

"It was very clear to me that this was someone who didn't quite trust what was going on," Prater says.

Within five minutes, Jabir left the room and ended the call.

But Jabir needed care. Prater says Jabir suffered from a kidney disorder called "nephrotic syndrome," where the body cannot filter protein, causing too much liquid to build up. As a result, the body experiences severe swelling and when that swelling goes unchecked, the liquid can sneak into the lungs, making it hard to breathe.

Prater wasn't the first physician to try to help. When Jabir arrived in St. Louis, he was offered in-home case management and in-home therapy services, Prater says. But Jabir refused almost everything.

That summer of 2021, he'd checked himself out of the hospital against medical advice after doctors tried to put a needle in him. He thought they were trying to kill him.

"He clearly has had trauma like most refugees, and particularly his case, a refugee of a civil war survivor," Prater says. "But for someone to have such mistrust that they weren't even able to engage in care is very unique."

Prater saw more than just physical ailments. He thought Jabir probably suffered from depression, anxiety and PTSD. To treat him, Prater had to earn Jabir's trust. On two separate weekends, he brought his kids to Hodiamont Avenue with fruit and a gift. They played soccer with Jabir's kids, and Prater introduced himself. One time, Jabir was quiet and hard to reach. Another time, Jabir warmed up to Prater, showed his personality and laughed with the kids.

On January 1, 2022, Prater got a call from the same neighbor who'd initially reached out about Jabir. Jabir, she said again, hadn't taken his medication in months, hadn't left his apartment in days and refused to visit the hospital. He looked like a ballooned version of himself –– his lips, his belly, his legs swollen –– with so much liquid built up that he had gained about 20 pounds. Parts of his body were so swollen that they were rock-hard.

When Prater arrived with Sudanese friends of Jabir's, the door to the apartment was closed and the lights were off. It was so dark, Prater had to shine a flashlight. He found Jabir sitting on his bed, hunched over. They could hear him breathing heavily, heaving in and out.

"This gentleman," Prater remembers, "needed medical urgent care."

By this point, Jabir recognized Prater. He agreed to visit the hospital –– but only if friends drove him.

Jabir spent the next few weeks in the hospital. He returned more energized and happier, a neighbor said. He expressed a desire to clean his apartment.

But it didn't last. That was the last time Prater saw Jabir.

"I probably knew his health best of anyone –– anyone, ever, in his life," Prater says. "And I never saw him in the office. So that, I think, paints a picture about how neglectful he was of his health. I mean, we tried to engage him and were not able to. And again, I'm not blaming him. I think he had serious mental health issues that we just couldn't ever break down. But for me to be the person that knew him best medically, that's really — that's sad."

On May 28, 2022, Jabir reached a turning point: He punched someone in his complex. The police arrived, without an interpreter, according to the social worker. In a report filed about the incident, the officers said that Jabir brandished a knife and resisted arrest.

This was Jabir's first arrest. The police took him to jail, where he was charged with felonies for unlawful use of a weapon and resisting arrest, along with two misdemeanor counts of assault in the fourth degree.

The rest of the details are murky. Documents from the 22nd Judicial Circuit Court show that a warrant was issued for Jabir's arrest on May 31. He was denied bond. But community members said he was released within a day or two. Neighbors were told that no charges had been filed. One searched his name on case.net and found nothing, assuming the situation blew over. (The charges didn't appear on case.net, according to multiple community members, until the day after he was killed.)

When Jabir came back, he didn't seem like himself. He was even worse than before: ashamed, rejected, resigned, one neighbor says. "It just was different."

But the arrest set other things into motion. Child Protective Services took Jabir's kids and put them in foster care. (Three of the four remained in foster care, not seeing their father for months before his death; the fourth, a teenager, soon slipped away and reunited with his father.)

Then on July 22, Jabir received an eviction notice.

A week before the killing, at the end of August, Jabir was kicked out of his apartment. The social worker called CPS and the police with the hopes they would place him in a shelter. But nothing happened. Some believe he stayed with friends. One night, a neighbor saw him sleeping in the grass. He might have stayed in the janitor's room. In his final few days, he started breaking into his old apartment and spending the nights there with one of his kids.

On Tuesday, September 6, Jabir once again broke into his apartment.

What happened next is unclear. Police say they arrived after receiving a disturbance call related to Jabir. The landlord informed them that Jabir had been evicted, but would not leave. When police approached, Jabir "became combative and armed himself with a knife and pole," Department of Public Safety spokesperson Monte Chambers says. They brought an interpreter, but Jabir "ignored the officer." The officers left and charged Jabir with resisting arrest, trespassing to the first degree and assault to the fourth degree, Chambers says.

Others heard it was a less fraught interaction. The landlord says an officer spent hours in Jabir's house. The next day, the same officer recited facts about Jabir's life to a social worker.

The varying accounts just add to the confusion surrounding what happened the following morning –– when heavily armed police arrived at Jabir's apartment.

The social worker with the Islamic Foundation had a plan for Wednesday, September 7: She was going to get Jabir help. She planned to check him into a shelter and take him to a psychiatric unit. There he could get on medication, move to a new apartment and get his kids back.

"I had it in my mind, Wednesday was game day –– we're gonna get him out and get him the help that he needs," the social worker says.

After the social worker arrived at work that morning, a family friend called her around 8:15 a.m. The friend said that police with automatic weapons had surrounded Jabir's apartment.

Chambers says the Fugitive Apprehension Street Team had come to arrest Jabir for his outstanding warrants from May and the day before. When they arrived that morning, Jabir "armed himself with an unknown object and barricaded himself in the apartment bathroom," Chambers says in a January 27 email to RFT.

But police have given different accounts of why they came to Jabir's apartment that day. A week after the shooting, police told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that they received a burglary call at 8:30 a.m. in the complex (though St. Louis police calls for service and police call records obtained by the Post-Dispatch indicate there was no burglary call at 8:30 a.m.). When they got there, police said they found Jabir and learned he had been evicted and had felony warrants. That's when the standoff started.

Regardless of what happened, it doesn't change one thing: The police surrounded Jabir's apartment. To community members, the show of force seemed excessive.

"Like, what are they doing?" the family friend says. "Are they here for an eviction? Like, this isn't an eviction process. Do they realize he's just a 61-year-old man? Why are they coming out like this? Do they think he has a bomb? Do they think he has a gun? Like, what is happening?"

The social worker rushed to the complex. When she got there at 8:45 a.m., she found multiple armed officers in bulletproof vests outside the door and windows to the apartment.

The social worker says she was "furious." She stormed past the gate around the complex, past the police officers, with no intention of stopping until she made it into the apartment and left with Jabir. "This was just ridiculous," she recalls. "This man hasn't done anything."

But the police stopped her. They told her they'd knocked on Jabir's door; he had a knife in his hand. They tried to shock him with a Taser, but Jabir dodged the attack (community members say he didn't understand the purpose of the Taser; he thought they were trying to kill him).

Police told the social worker Jabir had a long "rap sheet," but when the social worker searched his name later that afternoon, she couldn't find anything. They said not to worry –– they would get him out safely and take him to the hospital.

None of it made sense to the social worker.

"This is stupid. Let me just go in and get the guy out. I know him," she pleaded. "... I've never seen Bade with a knife."

Retelling the story, she pauses.

"Anyhow, it escalated."

Multiple people at the scene asked if they could go inside and get Jabir out. They told police that Jabir dealt with mental illness and police should call the Crisis Response Unit, which handles mental health crises. They told the police that Arabic was Jabir's second language, not his first, and that he sometimes struggled to communicate in Arabic. He might not understand them, they said –– especially in a high-stress situation. They told them that Jabir was not dangerous. He was frail, sick and 61 years old, in no condition to take down dozens of police officers. He was merely afraid, a man from a war-torn country, who had seen armed people come into his village and kill his neighbors.

He needed empathy –– not force.

A few hours into the standoff, police sent in a remote-controlled small robot on wheels with a microphone and camera, allowing Jabir to speak with another Sudanese refugee from a nearby village.

"I'm scared," the social worker remembers Jabir saying. "Please come into the home with me and walk out with me. I want to go back to Sudan."

But nothing changed. Police didn't budge. They didn't allow anyone inside, and they didn't call the Crisis Response Unit. Chambers tells the RFT that the Crisis Response Unit does not respond to "barricaded person or '7250' situations" because team members are "not trained negotiators."

Chambers adds via email that the police cannot allow bystanders "to negotiate with a barricaded person, for they may unintentionally escalate the situation. Secondly, we do not introduce individuals in barricaded or hostage situations as they may become potential hostages."

Instead, the police responded by bringing more police. Around 10:30 a.m., police called a SWAT team and additional officers to the scene, Chambers says. The social worker saw even more –– K9 dogs, people with U.S. Marshal jackets and lines of SUV cop cars. Between 11 a.m. and noon, they pushed the social worker and everyone further away from the apartment. They barricaded off the complex with yellow tape.

There was nothing community members could do.

"You guys are doing this wrong," the social worker told them. "This is all wrong."

Atak, another neighbor, arrived around noon, four hours after the standoff began. She couldn't believe her eyes. The night before she had talked to Jabir and made plans to help him find a new home. Now, dozens of police swarmed the man she had known for years, whom she describes as harmless. This must have been a misunderstanding, she thought. She volunteered to help Jabir safely out of the apartment. But the police denied her, too.

So Atak climbed the stairs of another building in the apartment complex. She watched as they threw multiple canisters of tear gas into the apartment, making everyone in the complex burst into tears.

Six hours after it began, after 2 p.m., she watched police enter the apartment. Additional officers in all black with riot gear, bulletproof vests and helmets crowded outside.

"Kobb al-sakina," the police said four times — "drop the knife" in Arabic.

Four seconds passed.

Then gunshots. POPOPOPOPOP. About nine shots, fired in rapid succession. There were a few seconds of quiet. Crickets hummed in the background. And then three seconds later, there was one more pop –– a final shot.

Minutes later, EMTs rolled Bade Ali Jabir's body into an ambulance and drove away without flashing their lights.

A few hours after Bade Ali Jabir was killed by police, St. Louis police Lieutenant John Green, commander of the Force Investigation Unit, stood in front of cameras at Hodiamont. A bright blue sky hung over him, with the brick apartments behind. He answered five questions and spoke for just over two minutes.

"Earlier this morning, our fugitive apprehension team was here to arrest a Sudanese Black male, 61 years of age, for some felony warrants," Green said. "When they arrived, he refused to come out and barricaded himself into the apartment."

Green ran through all of the tactics they tried. They sent in robots, he said, which Jabir "defeated," putting them in different rooms. They used tear gas and Jabir "hid" in the bathroom.

That's when SWAT entered the apartment, according to Green, where they found Jabir armed with a knife and a pole. He said they used Tasers, bean bags and tear gas to subdue him.

None of these measures worked.

"They end up shooting him," Green said.

When asked if the officers acted in self-defense, Green responded, "Yes."

Jabir would be the first of two people shot by police that week; Darryl Ross, a 16-year-old, was shot five days later, on September 12. Five people were killed by police in St. Louis in 2022 –– equal to the total number in the United Kingdom and Japan combined.

In a country where police killed 1,192 people in 2022, the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department was the nation's deadliest department, according to Mapping Police Violence. From 2013 to 2022, the department killed 48 people, or 15.9 people per 1 million residents. It was the highest rate in the country by a wide margin. The next highest was the Tulsa Police Department at 9.4 per 1 million.

In St. Louis, the overwhelming majority of people killed have been Black. A study conducted by ArchCity Defenders found that between 2009 and 2019, 72 percent of people killed by police in St. Louis were Black, even though Black people make up less than half of the city's total population.

Franklin Zimring, a professor of law at the University of California-Berkeley, studied police killings for his book When Police Kill. In a country where millions of citizens have guns and police are "armed and nervous," he finds the story of Jabir's killing all too familiar. Standoffs, he says, rarely help.

"[Standoffs] generate impatience on both ends," Zimring says, "and sometimes increase the emotional pressure to resolve, and that kind of emotional pressure generates impulses that are problematic if not restrained by clear administrative rules."

The most effective response, he says, is to let the standoff get "boring." But too often police escalate the standoffs. He says they often cite the presence of a knife as a justification for killing someone. A knife, though, rarely poses a threat to police, he argues.

"No police life insurance agency worries about knife threats from civilians as a cause of uniformed police officer death," he says. "They have to get awfully close."

For those who knew Jabir, the police narrative just doesn't add up.

"They portrayed Bade as some super warrior or superhuman," able to fend off Tasers, tear gas and an hours-long standoff, the social worker says.

Jabir could barely work a phone –– how could he dodge and "defeat robots?" Police say he trapped himself in the bathroom –– but how could he trap himself in the bathroom if the hinges were off the doors? Did Jabir even know he was wanted by the police?

Why didn't the police listen to those who knew Jabir best?

Why couldn't they just wait until he came out?

Why couldn't they subdue him without lethal force?

"It just seems like there were so many opportunities to take a different direction and then the other direction was taken," a neighbor says. "... And now there are four kids without a father or a mother."

Community members want to see the body camera footage and autopsy. They want clarity. They don't want police reports. They want evidence of what truly happened inside of Jabir's apartment. Friends of Jabir say the police have been conducting an internal investigation since the shooting, but nothing has surfaced.

Chambers, the police spokesman, says after the report is complete, it will be turned over to the circuit attorney to determine if there is criminal liability.

But to those who knew Jabir, the killing has haunted them. Jabir was a friend, a father of four, a fan of Sudanese music videos, a human being who was gentle, fearful, quiet, confused, complicated, resilient and loved.

The social worker can still see his body after the killing. His face without a jaw. His stomach, chest, lungs and leg riddled with bullet holes.

During an interview at a coffee shop nearly two months after the killing, Atak cries uncontrollably. "We're like family," she says.

The fellow Sudanese refugee, who is now a foster parent to Jabir's two sons, woke up every night for two weeks straight after the shooting with Jabir in his dreams.

Many use the word "tragic." Bade Ali Jabir fled war and left his home with hopes of finding a safer place for his kids. Instead, he was killed by the same people meant to protect him.

The door to Jabir's apartment is open. Wide open.

But on this day in December, Jabir isn't inside. He isn't outside either, sitting in his chair basking in the fresh air. In the place where Jabir once sat are a handful of buckets stacked on top of each other, spattered in paint. A couple of doors lean against the brick wall. Cardboard boxes with more blotches of paint, a hose, a wooden panel and bits of debris litter the grass.

The apartment is being redone –– ready for its next occupant. There's no indication that Jabir once lived there, that Jabir was shot to death there. The yellow tape, the broken windows, even the bullet holes are gone. Just a few buckets and a newly remodeled apartment that Jabir once tried to call home.

Coming soon: Riverfront Times Daily newsletter. We’ll send you a handful of interesting St. Louis stories every morning. Subscribe now to not miss a thing.Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter