Conner says he looks forward to the future legalization or decriminalization of psychedelics, but he's worried that attempts to treat these substances like pharmaceuticals could end up missing the point. He points to the trend of "microdosing" LSD, ostensibly allowing a user to remain functional while enjoying some visual effects and euphoria — but without the need to set aside six hours to journey across your mind's inner cosmos.

"But that's where the magic happens, that's where the work gets done," Conner emphasizes. "The experience is the healing, not the chemical."

Will Wisner, an Iraq War veteran who returned home with PTSD and survivor's guilt, is also wary of attempts to integrate psychedelics into the medical system that's failed so many veterans in the past. In recent years, Wisner has traveled outside the U.S. to undergo ayahuasca treatments, a physically draining psychedelic-ritual experience that involves a shaman and can take some sixteen hours per session.

Wisner is far from the only veteran to make the journey, but he stresses that the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has nothing to do with it.

"Right now, we are in a situation where we are a veteran space helping veterans, and we're going to do what the VA will not, or cannot, do," he says. "This is a spiritual thing. I wouldn't want to do ayahuasca with any doctor."

After a pause, he adds, "Unless it's a witch doctor."

Scientists are still grappling with what, exactly, a psychedelic experience represents. Is it something like a dream? A hallucination? The mind putting itself on the psychoanalyst's couch? Where does the mind go during an out-of-body experience? How can it observe itself?

For now, there are so many more questions than answers.

"What we do as humans is we make up a story about what we're perceiving," observes neuroscientist Dr. Joshua Siegel, who is part of a team of clinical researchers at Washington University currently studying the effects of psilocybin on the brain.

According to Siegel, the stories we tell ourselves contain real significance. While accounts of being separated from the ego or flying over your own consciousness might seem like nebulous hokum, Siegel notes that the number of people reporting similar themes during psychedelic experiences can't be waved off.

"Ego dissolution is fundamentally important from the therapeutic standpoint," he says. "A core feature of psychiatric illness is you're stuck in a maladaptive behavior, like depression, addiction, anxiety; the very experience of exiting your ego and your consciousness seems to help people to break the habit of behavior. No matter how they interpret it, experiencing your own death, flying like a bird, either way it can be useful."

But the mechanism for these experiences remains unclear. Dr. Ginger Nicol, a psychiatrist who leads Washington University's psychedelics research, points out that science still can't say whether the mystical experiences often described during psychedelic trips are required for the therapeutic effects to take hold, or something else entirely.

"As a psychiatrist, the human experience is really important, but mechanistically, and at the clinical level, can we measure that?" Nicol says. "If we can engineer it with a type of psychotherapy that targets a certain type of behavior — or if we could measure that experience — we could learn a lot about the human condition and what's it like to be alive and conscious."

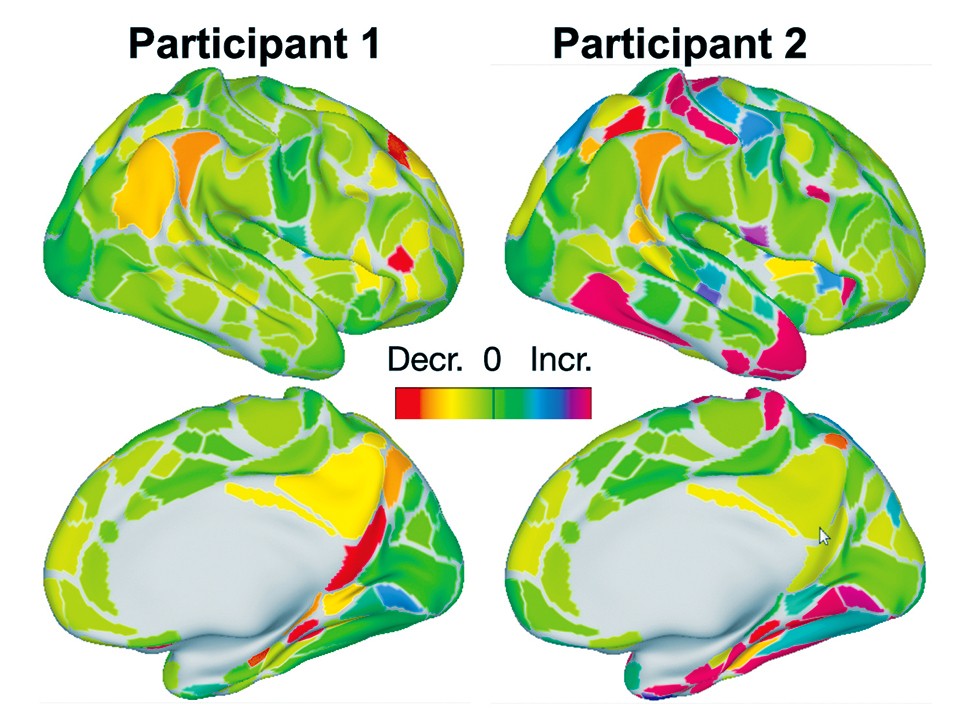

The duo's latest work involves a brain mapping study using subjects in the midst of a psilocybin trip. While the study involves a relatively small number of test subjects, Siegel says each test produces "a very large amount of data on each subject, and on how brain networks are changing from before, to during, to after a large dose."

For Nicol, the ultimate goal is to use psychedelics as a "precision medicine," targeting specific conditions with the right drug for the job. But after decades of restrictions on research, science is still far from cornering the truth on what a psychedelic experience actually represents.

"We're trying to understand what's happening to the brain during something subjective," Nicol admits. Both she and Siegel acknowledge that, even with the use of FMRI brain imaging, it's possible that psychedelics are changing the brain's structures in ways researchers haven't yet taken into account. For the researchers, that possibility could be skewing their results.

It's a fair question. Even with cutting-edge technology and detailed neural mapping, do we actually know what a brain on drugs looks like?

"Is what we're visualizing in the data actually the whole story?" Nicol wonders. "It's the irony — is what we're seeing reality?"

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]