This week's Riverfront Times explores our city's literary history. Check back throughout the week for online-only maps and articles supplementing this week's cover story.

After you've spent several weeks examining the literature of St. Louis, one thing becomes glaringly obvious: St. Louis' greatest literary glory -- like its greatest economic glory -- was about 100 years ago.

In older books, you can see vividly a St. Louis that no longer exits, with riverboats and streetcars and painfully accurate descriptions of the summer heat without relief from air-conditioning. (Now let us pause for a moment to praise this greatest of modern inventions.) Some of the street names are familiar, but the stores and houses look different, even in neighborhoods like the Central West End where the same houses still stand.

Mid-century, literary St. Louis became more abstract, captured more in poetry than in novels. Jonathan Franzen took pains to disguise it in The Corrections (but was anyone who knew St. Louis actually fooled by that "St. Jude" business?), and Laurell K. Hamilton dresses it up with vampires and fairies. Few modern novels try to capture St. Louis today as it really is.

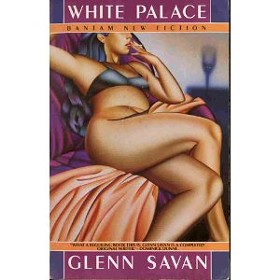

So if you have a few hours or days, find yourself a copy of Glenn Savan's White Palace. (It seems to be currently out of print, but copies are available online and at area libraries.) When it first came out in 1987, the LA Times called it "a surprising, mid-American love song," but it's more than that: it's possibly the great St. Louis novel.

White Palace concerns the relationship between Max, a recently-widowed 20something West County ad man, and Nora, a middle-aged woman from Dogtown who works behind the counter at the titular fast food joint at Grand and Gravois avenues that serves foul-smelling miniature hamburgers. They have interesting discussions about their class differences and also a lot of inventively-described sex.

Max and Nora move through a realistic St. Louis. Characters discuss St. Louis-centric topics, like where they went to high school. They use the term "hoosier" in its St. Louis sense, not as a nickname for a person from Indiana. And Savan describes, sometimes quite brilliantly, various aspects of St. Louis life. Here's a discussion between Max and a friend about St. Louis drivers:

"Do you know what this is? It's the typical passive St. Louis attitude. Why do you think nobody in this town uses their horns?" "What?" "You've driven in other cities. People use their goddamned horns in other cities. But not in St. Louis. You could run a red light and mow down an old lady and I guarantee you wouldn't hear a single horn. It's the same damned thing in movie theaters -- nobody ever turns around to tell loudmouths to shut up. They just sit there and suffer through it like it's their civic duty to be timid. And how about when that thirteen-year-old girl was raped in the fountain at Forest Park with a whole crowd of rubbernecks just standing there gawking?" "Max, what the hell are you talking about?" "I'm talking about how nobody in this city has the imagination to even know when they're getting crapped on."

And here is West Countian Max (though a graduate of U. City High!) venturing into pre-gentrification South City:

He was headed, after all, into the heart of darkness (it didn't matter that this South St. Louis neighborhood was mostly white), where the young men looked like roadies for heavy-metal bands, and the young women, already dragging one or two dirty toddlers behind them, were pregnant again, and where the drivers along Grand Avenue were even more savagely ignorant than usual. They waited to make their turns by jutting out halfway into intersections; when they weren't doubleparking they were lurching out of spaces along the congested street; they wove over the lines as if they were drunk, where they most likely were. Why couldn't people understand that they were sitting inside of deadly weapons?....Max crept along. He wondered why South St. Louisans were so much uglier than people, say, in Clayton or Ladue. It wasn't simply a matter of bad childhood nutrition; there were the barbaric beards and shaggy hair, the Budweiser T-shirts, the cheap rubber sandals from Woolworth's, the tattoos, the glum faces, the general uncleanliness to account for.

(Come to think of it, Savan might have been describing a certain breed of South City hipster.)

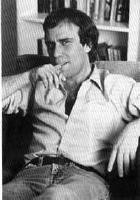

Part of White Palace's authenticity might stem from the fact that Savan was actually living here when he wrote it; a graduate of the Iowa Writer's Workshop, he gave up a career in advertising to wait tables for the three years it took him to finish the book.

A movie version of White Palace came out in 1990, starring Susan Sarandon and James Spader and filmed, in part, in St. Louis. (The exterior of Nora's house was an actual house in Dogtown at 1521 West Billon Avenue, behind the Denny's, but it was demolished in 1992.)

Savan would publish only one more novel, Goldman's Anatomy, which came out in 1993. He died in 2003 at the age of 49 after a long struggle with Parkinson's disease and degenerative joint ailments.

But we still have White Palace, a portrait of contemporary St. Louis.

Disagree with the notion that this is the Great St. Louis novel? Give us your nomination in the comments.