On Tuesday afternoon in the Wohl basketball gym, kids are screaming, coaches are yelling, balls are flying, parents are chatting, rap music is blaring and more balls are flying.

It's chaos.

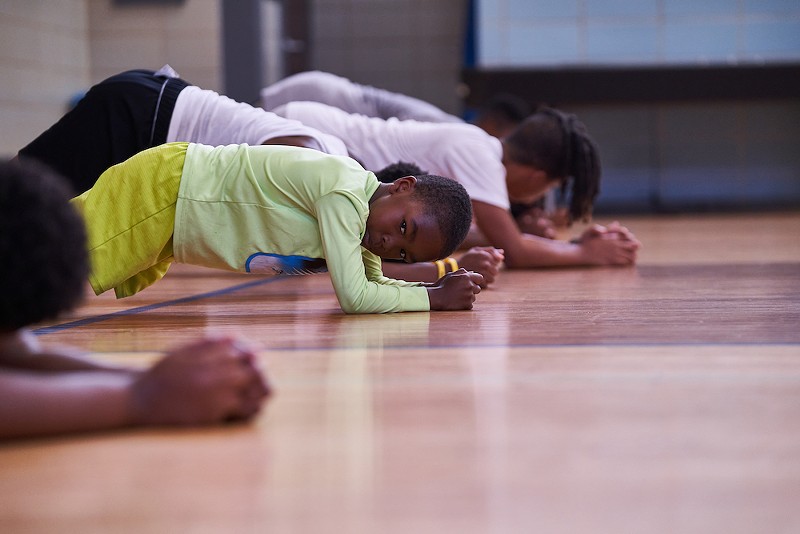

On one half of the court, a coach is putting on a workout for 10 kids, ranging from ages 3 to 15. On the other side of the court, a coach is running a kid through a cone drill, but instead of cones, they're using a combination of disc slam containers and pool noodles.

It looks like a normal rec center, but it's not supposed to look like a normal rec center. This place is supposed to be the mecca of basketball. It should, at the very least, be neatly organized, right? Or at least have a shooting machine or a coach with innovative drills that no other coach has or maybe a high-tech movie room, where people can break down jump shots.

Instead, it has Michael Nettles, the man who coached Tatum and, well, everyone. He's 58 years old and often sporting red-and-white Air Force 1s, a large silver cross, Celtics sweatpants, multiple variations of Celtics flat hats, sometimes an earring and sometimes a toothpick. He's technically a city staffer, serving as a recreation leader at the Wohl Center. Really, though, he runs the basketball gym.

But on this day, Nettles isn't coaching. He's just sitting on the sidelines and talking. Nettles is always talking. He mumbles fast. He throws out names of former St. Louis high school basketball players as if everyone knows them. He goes on long tangents about basketball philosophy and St. Louis basketball history.

Nettles talks to everyone. He knows everyone, usually, by a nickname he gave them — Too Tall, Lil Steph, Slaughter, Mohawk, T Mo, not to be confused with J Mo.

While the chaos rumbles along, a six-year-old girl walks up to Nettles. She calmly places her foot on his knee. Without pausing his conversation, Nettles ties one shoe and then the other.

Who is that?

"That's my Wohl grandbaby," he says.

Nettles grew up in north St. Louis. His father was a trash man and also worked in construction. His mother was a nurse at Homer G. Phillips, the acclaimed Black public hospital that closed in 1979. They weren't sports fans. His parents preached waking up early and studying in school.

Nettles got up at 4 a.m., but he didn't always do well in school. He constantly picked fights with bullies, he says, getting him kicked out of multiple middle schools. "I disliked the bullies," he says. "I hated bullies."

As the years went on, Nettles calmed down. He found solace in sports and played basketball at State Technical College of Missouri before transferring to Harris-Stowe State University.

He graduated in 1988, taught in schools and then, in 1992, took a job with the city's Department of Parks, Recreation and Forestry. He clocked in at every rec center in the city, he says. He even worked in the Medium Security Institution, better known as the Workhouse, where he reimagined the recreation program, adding handball, basketball tournaments and other activities.

Then, in 1996, Nettles arrived at Wohl. And he ruffled up the status quo.

"I had to go through certain things," Nettles says. "'You grown folks can't have the gym all damn day.' Boom, boom, boom. So, hey, I kicked them out. Some people didn't like me. I didn't care."

Nettles can be a loose cannon when he talks — or as he calls it, he "raw dogs it." "You jack off the game," he tells one of his players. "Byron ain't shit," he yells in the air, with Byron standing there. But this is just jokes, Nettles' famous banter.

If the Wohl Center has a beating heart, it is Nettles. He instantly knows when someone new is walking the hallways. "Hey hey hey!" he'll call after them. Then, he'll ask for your name, your story and, probably, your parents. Then, you can get a workout.

Kids are always in the gym. Kids from the neighborhood, kids whose parents drive them from the county –– even kids who don't play basketball but just want a place to hang.

On an afternoon in early August, a mom who hasn't brought her preteen son to Wohl in weeks walks into the rec center.

"I ain't messing with him," Nettles tells her. "He ain't no Wohl kid."

He'll let the kid work out, of course, but not before taking an opportunity to crack jokes at the mom's expense. Nettles rarely leaves the north side –– unless he's going to a travel basketball tournament. Recently, he went on vacation. Asked where he went, he said St. Louis. Where else would he go?

"I don't talk to her no more," he says about the mom to the crowd of people on the sideline. "She wanna spend all that money in the county and then come back!"

"He's only been out there for a month!" she protests.

For Nettles, that's a month he was at Wohl working with Wohl kids. Nettles doesn't use that phrase lightly: Wohl kids.

Wohl, or "Wohls" as most people call it, isn't only a noun to Nettles. It's an adjective. A Wohl kid is someone who is there all the time, week after week after week. "They tough. They mental. They prepared for life," Nettles says.

When a new peewee kid walks into the gym, Nettles introduces himself. "Hi, I'm Mike," he says, shaking the kid's hand, introducing him to Coach Stephon — alumnus and volunteer coach Stephon King — and sending him into an already-in-progress workout with teenagers.

"I'm not like everybody else," Nettles says. "Like, I work with everybody. ... I don't care what you've done. I care how you treat me. If you for real what you for real then I'm for real what you for real."

One day, he's teaching a three-year-old how to shoot. The kid catapults airball after airball on a mini-hoop. Nettles keeps grabbing the rebound and handing him the ball. It's like clockwork.

Airball.

"Catch it, and do it again, baby!" Nettles says.

Airball.

"Catch it, and do it again, baby!" Over and over again, until the kid is tired and needs some water.

"You getting it up there now, baby!" Nettles says, beaming.