When Wohl was opened in 1960, it was lauded as the best recreation center in the city. Through a city bond and a donation from David Wohl, owner of Wohl Shoe Company, the new building featured a pool, kitchen, multipurpose room and an NBA-length basketball court.

"An architectural gem from entrance to exit," the editor of the American Recreation Journal wrote at the time, "the Wohl Center is one of the nation's outstanding buildings."

It was also the best place to play basketball.

That stretched back decades, though, before Wohl was even built. Before Wohl, there was Sherman Community Center, located up the hill in Sherman Park. With multiple basketball courts, its basketball box scores ran in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch as early as the 1920s.

"It was the main place to play basketball," says Ron Golden, who lived in the neighborhood in the 1950s.

When Wohl replaced the former center in 1960, it inherited that basketball culture. During the 1980s, the Jodie Bailey Super Summer League, considered St. Louis' first comprehensive area-wide high school basketball league, took place at the Wohl Center. In the 1990s, there was the Midnight League, with games anywhere between 9 p.m. and 1 a.m. It was designed to keep people occupied during the night when crime often took place.

"It was the biggest for basketball in St. Louis," says Derrick Murray, who grew up going to the Wohl Center in the 1990s and 2000s. "Everybody from everywhere was coming to the Midnight League."

In 1995, Corey Frazier was a rising freshman on the Saint Louis University basketball team. But before he even played a game of college basketball, a teammate made him play at Wohl.

When he arrived on a Sunday evening, he was confused about what made this place so special. The gym was dim, and the rims were too high. No one cared, or knew, about Frazier's pedigree as a prized recruit. His opponents talked trash, never let him call a foul and made him power through every bucket.

"I earned my respect in St. Louis that day," says Frazier, now a professional skills trainer.

Then during the late 1990s, Wohl went through a rough patch, says Lamont "Pat" Johnson, who volunteer coached at Wohl for two decades. The Midnight League organizers were accused of stealing nearly $60,000 of donated money from the league from 1995 to 1996. Shortly after in October 1997, a year after Mike Nettles arrived, one of the rec center's most promising alumni, Sean Tunstall, who played at the University of Kansas, was shot and killed in Wohl's parking lot.

There was a "stigma around the Wohl Center," Johnson says.

Originally from the 12th & Park Recreation Center, Johnson started coaching at Wohl in 1998. Picking up his sisters from summer camp, he saw Nettles on the baseball field trying to train 20 kids in T-ball. Johnson, who'd served time in jail, recognized Nettles from his stint as a staffer at the Workhouse and offered to help. "I knew he couldn't teach all of them at the same time," Johnson says.

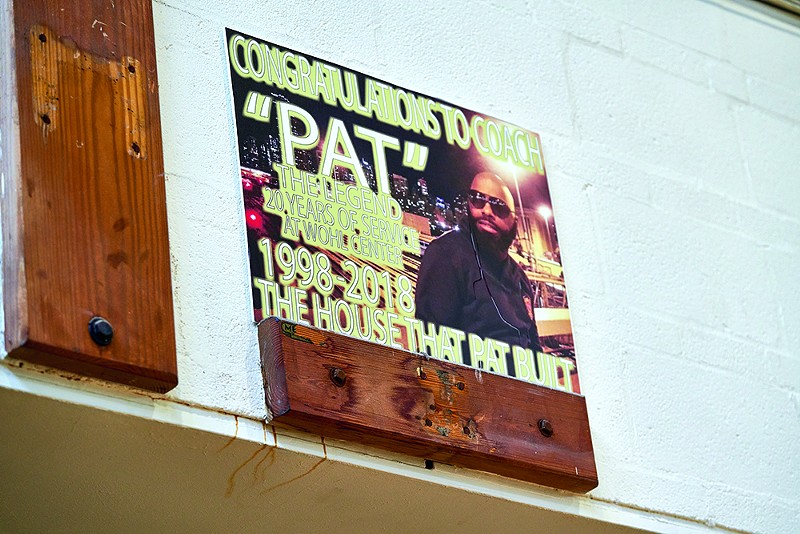

For two decades, Johnson coached at Wohl. Although he left in 2018 to return to 12th & Park, a banner hangs in the gym declaring Wohl "the house that Pat built." Over time, he helped Nettles organize workouts, in-house leagues, city-wide leagues and, eventually, travel teams that were separate from the Wohl Center.

In the 2000s, the gym had all kinds of leagues — high school leagues and women's leagues and peewee leagues. Mike Nettles would ref the games, and he pissed off everyone –– players, coaches and fans alike — because he rarely called fouls, and he rigged the games, so they would always end in a close score.

On a typical weekday afternoon, a sea of people crowded the gym. A line snaked outside of the kitchen and the smell of fries filled the air. There were never enough places to sit, and most fans spent the afternoons standing. Cars filled the lot, street and grass around the center. "If you could [park in the parking lot]," Miles Nettles, Mike Nettles' son, remembers, "you got a good parking spot."

Wohl always seemed to be open. The coaches held basketball activities on weekends and late at night. If there wasn't a league game, there was always pickup. And if you didn't like basketball, there were always programs outside of basketball –– karate, summer camp, dance, football, cheerleading and boxing.

Even after the rec center closed for the night, the older guys went to the kitchen to play dominoes or dice or pool. Kids would stay in the gym to shoot hoops.

Throughout it all, Nettles and Johnson, who was a full-time volunteer, stayed together and built Wohl's reputation as a training ground for youth players, with a focus on fundamentals. They forced kids to dribble with two balls, practice weaving through cones, shoot baskets with boxing gloves on and dance in the defensive stance to the "Cha-Cha Slide."

"I love Mike to death," says Tatum's mom, Cole-Barnes. "But even if it wasn't the most organized, if you didn't have enough advance notice, you knew if you showed up that, at some point, if there's enough kids in the gym, we're playing basketball. Mike is gonna go in the back and pull out jerseys."

Over the years, though, the neighborhood around Sherman Park experienced a dramatic population loss. Once a middle-class Black community in the 1960s and '70s, when Wohl was first founded, the area struggled through decades of disinvestment. Businesses closed their doors, houses became vacant lots, baseball fields grew weeds and crime increased. The city did little to reverse the neighborhood's decline. People left in flocks.

From 2000 to 2020, each of the four neighborhoods bordering Wohl lost population –– dropping by, on average, 38 percent. In Kingsway East, for example, the population fell from 3,797 to 2,355.

Quite literally, there were fewer kids in the community for Wohl to pull from. And they had fewer resources to provide for the kids that did stop by.

For decades, funding across rec centers in the city continued to decrease, says the city's recreation department director, Evelyn Rice. Staff members were laid off. Some rec centers had to close over the weekend. Others shut down altogether. In 1960, for example, when Wohl was first built, there were more than 10 city recreation centers. Now there are only six.

That's changing now, little by little. Under Mayor Tishaura Jones' administration, funding has increased, with an influx of ARPA funds, allowing the centers to re-hire staff, open during the weekend and bring back programming, such as singing, dance, photography and maybe even another version of the Midnight League.

But even during those "lean years," Rice says, she would drive by Wohl when it was "closed" for the weekend, only to find it open. There would be Nettles coaching or Dana Moorehead, the recreation center director, watching kids.

"When the staffing gets cut, then you can't offer programs as frequently," she says. "You can still do basketball but not to the level and extent you want to."

She pauses.

"Unless you have somebody like a Mike Nettles, who does it anyway."